| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 85,000 - 120,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Lisbon · Porto · Algarve · São Teotónio ·Pegões (Montijo) · Santarém, Benavente | |

| Languages | |

| Portuguese · Konkani · Tamil · Malayalam · Gujarati · English · language · Hindi | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Roman Catholicism) · Hinduism · Sikhism · Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Konkani people, Non-resident Indian and Person of Indian Origin, Desi, Nepali, Indian immigration to Brazil, Indians in Spain |

Indians in Portugal , including recent immigrants and people who trace their ancestry back to India, together number around 80,000 (2018 data) [1] -120,000 (2021 data). [2] Between 2018 and 2022 around 32,000 Indians entered the country, settling mostly in Lisbon and Porto. [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] They thus constitute 0.76% - 1.15% of the total population of Portugal.

Indians are also found in the Algarve, Coimbra, Guarda, Leiria, Odemira [8] and Rio Maior. [9]

The majority of Indians in Portugal consist of Goans, Gujaratis, Tamilians, Malayali people from Daman and Diu and Tamil Nadu.

The 2010s, particularly the second half of the decade, saw the start of a new immigration wave of Indians to Portugal, as well as of citizens of other South Asian nationals - namely Nepalis, Bengalis and Pakistanis - propelled mainly by the need of unskilled agricultural workers.

In sixteenth century southern Portugal, there were Chinese slaves but the number of them was described as "negligible", being outnumbered by East Indian, Mourisco, and African slaves. [10] Amerindians, Chinese, Malays, and Indians were slaves in Portugal but in far fewer number than Turks, Berbers and Arabs. [11] China and Malacca were origins of slaves delivered to Portugal by Portuguese viceroys. [12]

A Portuguese woman, Dona Ana de Ataíde owned an Indian man named António as a slave in Évora. [13] He served as a cook for her. [14] Ana de Ataíde's Indian slave escaped from her in 1587. [15] A large number of slaves were forcibly brought there since the commercial, artisanal, and service sectors all flourished in a regional capital like Évora. [16] Rigorous and demanding tasks were assigned to Mourisco, Chinese, and Indian slaves. [17] Chinese, Mouriscos, and Indians were among the ethnicities of prized slaves and were much more expensive compared to blacks, so high class individuals owned these ethnicities. [18]

A fugitive Indian slave from Evora named António went to Badajoz after leaving his master in 1545. [19] António was among the three most common male names given to male slaves in Evora. [20]

Antão Azedo took an Indian slave named Heitor to Evora, who along with another slave was from Bengal were among the 34 Indian slaves in total who were owned by Tristão Homem, a nobleman in 1544 in Evora. Manuel Gomes previously owned a slave who escaped in 1558 at age 18 and he was said to be from the "land of Prester John of the Indias" named Diogo. [21]

In Evora, men were owned and used as slaves by female establishments like convents for nuns. A capelão do rei, father João Pinto left an Indian man in Porto where he was picked up in 1546 by the Evora-based Santa Marta convent's nuns to serve as their slave. However, female slaves did not serve in male establishments, unlike vice versa. [22]

Japanese Christian Daimyos mainly responsible for selling to the Portuguese their fellow Japanese. Japanese women and Japanese men, Javanese, Chinese, and Indians were all sold as slaves in Portugal. [23]

Traits such as high intelligence were ascribed to Indians, Chinese, and Japanese slaves. [24] [25] [26]

Alexandre Herculano de Carvalho e Araújo was a Portuguese novelist and historian.

The Santa Justa Lift, also called Carmo Lift, is an elevator, or lift, in the civil parish of Santa Justa, in the historic center of Lisbon, Portugal. Situated at the end of Rua de Santa Justa, it connects the lower streets of the Baixa with the higher Largo do Carmo.

The Mahi are a people of Benin. They live north of Abomey, from the Togo border on the west to the Zou River on the east, and south to Cové between the Zou and Ouemé rivers, north of the Dassa hills.

Garcia Fernandes was a Portuguese Renaissance painter. Like many of painters of the time, Garcia Fernandes was a pupil in the Lisbon workshop of Jorge Afonso, who was the court painter of King Manuel I.

Sancho de Tovar, 6th Lord of Cevico, Caracena and Boca de Huérgano was a Portuguese nobleman of Castilian birth, best known as a navigator and explorer during the Portuguese age of discoveries. He was the vice-admiral (soto-capitão) of the fleet that discovered Brazil in 1500, and was later appointed Governor of the East African port-city of Sofala by king Manuel I. In this post, he conducted several exploratory missions in the interior regions of present-day Mozambique.

The Igreja de São Roque is a Catholic church in Lisbon, Portugal. It was the earliest Jesuit church in the Portuguese world, and one of the first Jesuit churches anywhere. The edifice served as the Society's home church in Portugal for over 200 years, before the Jesuits were expelled from that country. After the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, the church and its ancillary residence were given to the Lisbon Holy House of Mercy to replace their church and headquarters which had been destroyed. It remains a part of the Holy House of Mercy today, one of its many heritage buildings.

André Ferreira da Silva, better known by his pen name André Vianco, is a Brazilian best-selling novelist, screenwriter, and film and television director. Specialized in urban fantasy and horror, supernatural and vampire fiction, he rose to fame in 1999 with the novel Os Sete. As of 2016, his books have sold over a million copies, and in 2018 he was named, alongside Max Mallmann, Raphael Draccon and Eduardo Spohr, one of the leading Brazilian fantasy writers of the 21st century.

Chinese people in Portugal form the country's largest Asian community, and the twelfth-largest foreign community overall. Despite forming only a small part of the overseas Chinese population in Europe, the Chinese community in Portugal is one of the continent's oldest due to the country's colonial and trade history with Macau dating back to the 16th century. There are about 30,000 people of Chinese descent residing in Portugal

José António Nunes Mexia Beja da Costa Falcão is a Portuguese art historian, museum curator and educator.

The Fort of Cinco Ribeiras, also known as the Fort of Nossa Senhora do Pilar or Fort of São Bartolomeu, ruins of a 16th-century fortification located in the municipality of Angra do Heroísmo, along the southeast coast of Terceira, Portuguese archipelago of the Azores.

Fort of the Cavalas is a fort situated in the civil parish of São Sebastião in the municipality of Angra do Heroísmo, in the Portuguese archipelago of the Azores.

Luís Gonzaga Pinto da Gama was a Brazilian rábula, abolitionist, orator, journalist and writer, and the Patron of the abolition of slavery in Brazil.

Slavery in Portugal existed since before the country's formation. During the pre-independence period, inhabitants of the current Portuguese territory were often enslaved and enslaved others. After independence, during the existence of the Kingdom of Portugal, the country played a leading role in the Atlantic slave trade, which involved the mass trade and transportation of slaves from Africa and other parts of the world to the American continent. The import of slaves was banned in European Portugal in 1761 by the Marquês de Pombal. However, slavery within the African Portuguese colonies was only abolished in 1869.

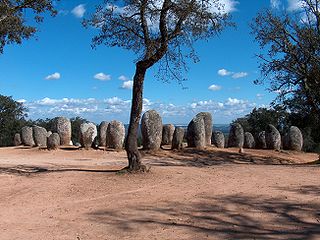

The Cromlech of the Almendres is a megalithic complex, located 4.5 road km WSW of the village of Nossa Senhora de Guadalupe, in the civil parish of Nossa Senhora da Tourega e Nossa Senhora de Guadalupe, municipality of Évora, in the Portuguese Alentejo. The largest existing group of structured menhirs in the Iberian Peninsula, this archaeological site consists of several megalithic structures: cromlechs and menhir stones, that belong to the so-called "megalithic universe of Évora", with clear parallels to other cromlechs in Évora District, such as Portela Mogos and the Vale Maria do Meio Cromlech.

Augusto Carlos Teixeira de AragãoComA • CavC • CavA • CavTE was a Portuguese officer, doctor, numismatist, archaeologist and historian. As an officer of the Portuguese army, he retired with the rank of general. Teixeira de Aragão is considered one of the "fathers" of Portuguese numismatics.

Jurubaça was a term for interpreter in the Portuguese colonies of Southeast Asia and the Far East, particularly in Macau. The term is prevalent in mid-sixteenth- through eighteenth-century documents. According to the Grande Dicionário da Língua Portuguesa, a Jurubaça was an “Antigo intérprete da Malásia e do Extremo Oriente,” an ancient interpreter in Malaysia and the Far East. The word derives from Malay jurubassa, which translates as a person who is an interpreter. The earliest document utilizing the word iurubaças dates from the sixteenth century.

Martim Afonso de Melo (1360–1432) was a Portuguese nobleman, Lord of Arega and Barbacena. He served as Alcaide of Évora, and Guarda-mor of John I of Portugal.

The Atlantic slave trade to Brazil occurred during the period of history in which there was a forced migration of Africans to Brazil for the purpose of slavery. It lasted from the mid-sixteenth century until the mid-nineteenth century. During the trade, more than three million Africans were transported across the Atlantic and sold into slavery. It was divided into four phases: The Cycle of Guinea ; the Cycle of Angola which trafficked people from Bakongo, Mbundu, Benguela and Ovambo; Cycle of Costa da Mina, now renamed Cycle of Benin and Dahomey, which trafficked people from Yoruba, Ewe, Minas, Hausa, Nupe and Borno; and the Illegal trafficking period, which was suppressed by the United Kingdom (1815-1851). During this period, to escape the supervision of British ships enforcing an anti-slavery blockade, Brazilian slave traders began to seek alternative routes to the routes of the West African coast, turning to Mozambique.

Caralho is a vulgar Portuguese-language word with a variety of meanings and uses. Literally, it is a noun referring to the penis, similar to English dick, but it is also used as an interjection expressing surprise, admiration, or dismay in both negative and positive senses in the same way as fuck in English. Caralho is also used in the intensifiers para caralho, placed after adjectives and sometimes adverbs and nouns to mean "very much" or "lots of", and do caralho, both of which are equivalent to the English vulgarities fucking and as fuck.

Anarchism in Portugal first appeared in the form of organized groups in the mid-1880s. It was present from the first steps of the workers' movement, revolutionary unionism and anarcho-syndicalism had a lasting influence on the General Confederation of Labour, founded in 1919.