The Mayan languages form a language family spoken in Mesoamerica and northern Central America. Mayan languages are spoken by at least 6 million Maya peoples, primarily in Guatemala, Mexico, Belize and Honduras. In 1996, Guatemala formally recognized 21 Mayan languages by name, and Mexico recognizes eight more within its territory.

Kʼicheʼ are indigenous peoples of the Americas and are one of the Maya peoples. The Kʼicheʼ language is a Mesoamerican language in the Mayan language family. The highland Kʼicheʼ states in the pre-Columbian era are associated with the ancient Maya civilization, and reached the peak of their power and influence during the Mayan Postclassic period. The meaning of the word Kʼicheʼ is "many trees". The Nahuatl translation, Cuauhtēmallān "Place of the Many Trees (People)", is the origin of the word Guatemala. Quiché Department is also named for them. Rigoberta Menchú, an activist for indigenous rights who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1992, is perhaps the best-known Kʼicheʼ.

Mam is a Mayan language spoken by about half a million Mam people in the Guatemalan departments of Quetzaltenango, Huehuetenango, San Marcos, and Retalhuleu, and the Mexican state of Chiapas. Thousands more make up a Mam diaspora throughout the United States and Mexico, with notable populations living in Oakland, California and Washington, D.C.

Tzeltal or Tsʼeltal is a Mayan language spoken in the Mexican state of Chiapas, mostly in the municipalities of Ocosingo, Altamirano, Huixtán, Tenejapa, Yajalón, Chanal, Sitalá, Amatenango del Valle, Socoltenango, Las Rosas, Chilón, San Juan Cancuc, San Cristóbal de las Casas and Oxchuc. Tzeltal is one of many Mayan languages spoken near this eastern region of Chiapas, including Tzotzil, Chʼol, and Tojolabʼal, among others. There is also a small Tzeltal diaspora in other parts of Mexico and the United States, primarily as a result of unfavorable economic conditions in Chiapas.

Tzotzil is a Maya language spoken by the indigenous Tzotzil Maya people in the Mexican state of Chiapas. Most speakers are bilingual in Spanish as a second language. In Central Chiapas, some primary schools and a secondary school are taught in Tzotzil. Tzeltal is the most closely related language to Tzotzil and together they form a Tzeltalan sub-branch of the Mayan language family. Tzeltal, Tzotzil and Chʼol are the most widely spoken languages in Chiapas.

Halkomelem is a language of various First Nations peoples in British Columbia, ranging from southeastern Vancouver Island from the west shore of Saanich Inlet northward beyond Gabriola Island and Nanaimo to Nanoose Bay and including the Lower Mainland from the Fraser River Delta upriver to Harrison Lake and the lower boundary of the Fraser Canyon.

Xquic is a mythological figure known from the 16th century Kʼicheʼ manuscript Popol Vuh. She was the daughter of one of the lords of Xibalba, called Cuchumaquic, Xibalba being the Maya Underworld. Noted particularly for being the mother of the Maya Hero Twins, Hunahpu and Xbalanque, she is sometimes considered to be the Maya goddess associated with the waning moon. However, there is no evidence for this in the Popol Vuh text itself.

The Kaqchikel language is an indigenous Mesoamerican language and a member of the Quichean–Mamean branch of the Mayan languages family. It is spoken by the indigenous Kaqchikel people in central Guatemala. It is closely related to the Kʼicheʼ (Quiché) and Tzʼutujil languages.

The Qʼeqchiʼ language, also spelled Kekchi, Kʼekchiʼ, or kekchí, is one of the Mayan languages, spoken within Qʼeqchiʼ communities in Guatemala and Belize.

Chuj is a Mayan language spoken by around 40,000 members of the Chuj people in Guatemala and around 3,000 members in Mexico. Chuj is a member of the Qʼanjobʼalan branch along with the languages of Tojolabʼal, Qʼanjobʼal, Akateko, Poptiʼ, and Mochoʼ which, together with the Chʼolan branch, Chuj forms the Western branch of the Mayan family. The Chujean branch emerged approximately 2,000 years ago. In Guatemala, Chuj speakers mainly reside in the municipalities of San Mateo Ixtatán, San Sebastián Coatán and Nentón in the Huehuetenango Department. Some communities in Barillas and Ixcán also speak Chuj. The two main dialects of Chuj are the San Mateo Ixtatán dialect and the San Sebastián Coatán dialect.

Ixil (Ixhil) is one of the 21 different Mayan languages spoken in Guatemala. According to historical linguistic studies Ixil emerged as a separate language sometime around the year 500AD. It is the primary language of the Ixil people, which comprises the three towns of San Juan Cotzal, Santa Maria Nebaj, and San Gaspar Chajul in the Guatemalan highlands. There is also an Ixil speaking migrant population in Guatemala City and the United States. Although there are slight differences in vocabulary in the dialects spoken by people in the three different Ixil towns, they are all mutually intelligible and should be considered dialects of a single language.

Itzaʼ is a critically endangered Mayan language spoken by the Itza people near Lake Peten Itza in north-central Guatemala. The language has only 25 fluent speakers and 60 nonfluent speakers.

Mopan is a language that belongs to the Yucatecan branch of the Mayan languages. It is spoken by the Mopan people who live in the Petén Department of Guatemala and in the Maya Mountains region of Belize. There are between three and four thousand Mopan speakers in Guatemala and six to eight thousand in Belize.

The Uspanteko is a Mayan language of Guatemala, closely related to Kʼicheʼ. It is spoken in the Uspantán and Playa Grande Ixcán municipios, in the Department El Quiché. It is also one of only three Mayan languages to have developed contrastive tone. It distinguishes between vowels with high tone and vowels with low tone.

Tzʼutujil is a Mayan language spoken by the Tzʼutujil people in the region to the south of Lake Atitlán in Guatemala. Tzʼutujil is closely related to its larger neighbors, Kaqchikel and Kʼicheʼ. The 2002 census found 60,000 people speak Tzʼutujil as their mother tongue. The two Tzʼutijil dialects are Eastern and Western.

Tsimshian, known by its speakers as Sm'álgyax, is a dialect of the Tsimshian language spoken in northwestern British Columbia and southeastern Alaska. Sm'algyax means literally "real or true language."

Qʼanjobʼal is a Mayan language spoken primarily in Guatemala and part of Mexico. According to 1998 estimates compiled by SIL International in Ethnologue, there were approximately 77,700 native speakers, primarily in the Huehuetenango Department of Guatemala. Municipalities where the Qʼanjobʼal language is spoken include San Juan Ixcoy, San Pedro Soloma, Santa Eulalia, Santa Cruz Barillas (Yalmotx), San Rafael La Independencia, and San Miguel Acatán. Qʼanjobʼal is taught in public schools through Guatemala's intercultural bilingual education programs.

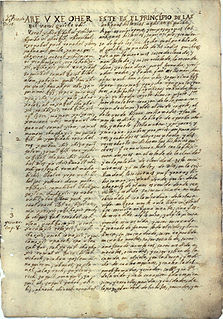

Classical Kʼicheʼ was an ancestral form of the modern-day Kʼicheʼ language, which was spoken in the highland regions of Guatemala around the time of the 16th century Spanish conquest of Guatemala. Classical Quiché has been preserved in a number of historical Mesoamerican documents, lineage histories, missionary texts and dictionaries, and is the language in which the renowned highland Maya creation account Popol Vuh is written.

Cauque Mayan is a mixed language, a Kʼicheʼ (Quiché) base relexified by Kaqchikel (Cakchiquel). During the colonial era, Kʼicheʼ migrated to Sacatepéquez, in the heart of Kaqchikel territory, where they founded the village of Santa María Cauque. Today only older adults retain the Kʼicheʼ base to their speech: for younger speakers, the language has merged into Kaqchikel.