The Ojibwe, Ojibwa, Chippewa, or Saulteaux are an Anishinaabe people in what is currently southern Canada, the northern Midwestern United States, and Northern Plains. They are Indigenous peoples of the Subarctic and Northeastern Woodlands.

Chippewa is an alternate term for the Ojibwe tribe of North America.

Sandy Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa are a historical Ojibwa tribe located in the upper Mississippi River basin, on and around Big Sandy Lake in what today is in Aitkin County, Minnesota. Though politically folded into the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, thus no longer independently federally recognized, for decades, Sandy Lake Band members have been leading efforts to restore their independent Federal recognition.

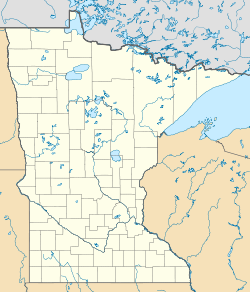

Mille Lacs Indian Reservation is the popular name for the land-base for the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe in Central Minnesota, about 100 miles (160 km) north of Minneapolis-St. Paul. The contemporary Mille Lacs Band reservation has significant land holdings in Mille Lacs, Pine, Aitkin and Crow Wing counties, as well as other land holdings in Kanabec, Morrison, and Otter Tail Counties. Mille Lacs Indian Reservation is also the name of a formal Indian reservation established in 1855. It is one of the two formal reservations on which the contemporary Mille Lacs Band retains land holdings. The contemporary Mille Lacs band includes several aboriginal Ojibwe bands and villages, whose members reside in communities throughout central Minnesota.

The Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, also known as the Mille Lacs Band of Chippewa Indians, is a federally recognized American Indian tribe in east-central Minnesota. The Band has 4,302 members as of 2012. Its homeland is the Mille Lacs Indian Reservation, consisting of District I, District II, District IIa, and District III.

The St. Croix Chippewa Indians are a historical Band of Ojibwe located along the St. Croix River, which forms the boundary between the U.S. states of Wisconsin and Minnesota. The majority of the St. Croix Band are divided into two groups: the federally recognized St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Wisconsin, and the St. Croix Chippewa Indians of Minnesota, who are one of four constituent members forming the federally recognized Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe. The latter is one of six bands in the federally recognized Minnesota Chippewa Tribe.

The Mille Lacs Indians, also known as the Mille Lacs and Snake River Band of Chippewa, are a Band of Indians formed from the unification of the Mille Lacs Band of Mississippi Chippewa (Ojibwe) with the Mille Lacs Band of Mdewakanton Sioux (Dakota). Today, their successor apparent Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe consider themselves as being Ojibwe, but many on their main reservation have the ma'iingan (wolf) as their chief doodem (clan), which is an indicator of Dakota origins.

The Treaty of La Pointe may refer to either of two treaties made and signed in La Pointe, Wisconsin between the United States and the Ojibwe (Chippewa) Native American peoples. In addition, the Isle Royale Agreement, an adhesion to the first Treaty of La Pointe, was made at La Pointe.

Mississippi River Band of Chippewa Indians or simply the Mississippi Chippewa, are a historical Ojibwa Band inhabiting the headwaters of the Mississippi River and its tributaries in present-day Minnesota.

Pillager Band of Chippewa Indians are a historical band of Chippewa (Ojibwe) who settled at the headwaters of the Mississippi River in present-day Minnesota. Their name "Pillagers" is a translation of Makandwewininiwag, which literally means "Pillaging Men". The French called them Pilleurs, also a translation of their name. The French and Americans adopted their autonym for their military activities as the advance guard of the Ojibwe in the invasion of the Dakota country.

Chief Buffalo was a major Ojibwa leader, born at La Pointe in Lake Superior's Apostle Islands, in what is now northern Wisconsin, USA.

The Sandy Lake Tragedy was the culmination in 1850 of a series of events centered in Big Sandy Lake, Minnesota that resulted in the deaths of several hundred Lake Superior Chippewa. Officials of the Zachary Taylor Administration and Minnesota Territory sought to relocate several bands of the tribe to areas west of the Mississippi River. By changing the location for fall annuity payments, the officials intended the Chippewa to stay at the new site for the winter, hoping to lower their resistance to relocation. Due to delayed and inadequate payments of annuities and lack of promised supplies, about 400 Ojibwe, mostly men and 12% of the tribe, died of disease, starvation and cold. The outrage increased Ojibwe resistance to removal. The bands effectively gained widespread public support to achieve permanent reservations in their traditional territories.

The Lake Superior Chippewa are a large number of Ojibwe (Anishinaabe) bands living around Lake Superior; this territory is considered part of northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota in the United States. They migrated into the area by the seventeenth century, encroaching on the Eastern Dakota people who had historically occupied the area. The Ojibwe defeated the Eastern Dakota, who migrated west into the Great Plains after the final battle in 1745. While they share a common culture including the Anishinaabe language, this highly decentralized group of Ojibwe includes at least twelve independent bands in the region.

Lac Courte Oreilles is a large freshwater lake located in northwest Wisconsin in Sawyer County in townships 39 and 40 north, ranges 8 and 9 west. It is irregular in shape, having numerous peninsulas and bays, and is approximately six miles long in a southwest to northeast direction and with a maximum width of about two miles (3 km). Lac Courte Oreilles is 5,039 acres (20.39 km2) in size with a maximum depth of 90 feet (27 m) and a shoreline of 25.4 miles (40.9 km). The lake has a small inlet stream that enters on the northeast shore of the lake and flows from Grindstone Lake, a short distance away to the north. An outlet on the southeast shore of the lake leads through a very short passage to Little Lac Courte Oreilles, then via the Couderay River to the Chippewa River, and ultimately to the Mississippi River at Lake Pepin.

Chief Beautifying Bird or Dressing Bird, (1794–1855) was a principal chief of the Prairie Rice Lake Band of the Lake Superior Chippewa, originally located near Rice Lake, Wisconsin. He served as the principal chief about the middle of the 19th century.

Treaty of St. Peters may be one of two treaties conducted between the United States and Native American peoples, conducted at the confluence of the Minnesota River with the Mississippi River, in what today is Mendota, Minnesota.

Sandy Lake is an unincorporated community Native American village located in Turner Township, Aitkin County, Minnesota, United States. Its name in the Ojibwe language is Gaa-mitaawangaagamaag, meaning "Place of the Sandy-shored Lake". The village is administrative center for the Sandy Lake Band of Mississippi Chippewa, though the administration of the Mille Lacs Indian Reservation, District II, is located in the nearby East Lake.

The Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC) is an intertribal, co-management agency committed to the implementation of off-reservation treaty rights on behalf of its eleven-member Ojibwa tribes. Formed in 1984 and exercising authority specifically delegated by its member tribes, GLIFWC's mission is to help ensure significant off-reservation harvests while protecting the resources for generations to come.

An act for the relief and civilization of the Chippewa Indians in the State of Minnesota, commonly known as the Nelson Act of 1889, was a United States federal law intended to relocate all the Anishinaabe people in Minnesota to the White Earth Indian Reservation in the western part of the state, and expropriate the vacated reservations for sale to European settlers.