Tracheal intubation, usually simply referred to as intubation, is the placement of a flexible plastic tube into the trachea (windpipe) to maintain an open airway or to serve as a conduit through which to administer certain drugs. It is frequently performed in critically injured, ill, or anesthetized patients to facilitate ventilation of the lungs, including mechanical ventilation, and to prevent the possibility of asphyxiation or airway obstruction.

Mechanical ventilation, assisted ventilation or intermittent mandatory ventilation (IMV), is the medical term for using a machine called a ventilator to fully or partially provide artificial ventilation. Mechanical ventilation helps move air into and out of the lungs, with the main goal of helping the delivery of oxygen and removal of carbon dioxide. Mechanical ventilation is used for many reasons, including to protect the airway due to mechanical or neurologic cause, to ensure adequate oxygenation, or to remove excess carbon dioxide from the lungs. Various healthcare providers are involved with the use of mechanical ventilation and people who require ventilators are typically monitored in an intensive care unit.

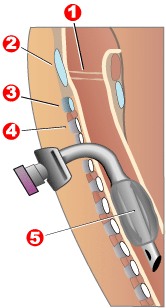

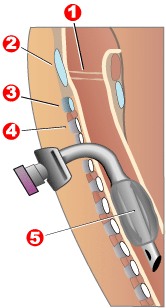

Tracheotomy, or tracheostomy, is a surgical airway management procedure which consists of making an incision (cut) on the anterior aspect (front) of the neck and opening a direct airway through an incision in the trachea (windpipe). The resulting stoma (hole) can serve independently as an airway or as a site for a tracheal tube or tracheostomy tube to be inserted; this tube allows a person to breathe without the use of the nose or mouth.

Laryngoscopy is endoscopy of the larynx, a part of the throat. It is a medical procedure that is used to obtain a view, for example, of the vocal folds and the glottis. Laryngoscopy may be performed to facilitate tracheal intubation during general anaesthesia or cardiopulmonary resuscitation or for surgical procedures on the larynx or other parts of the upper tracheobronchial tree.

A tracheal tube is a catheter that is inserted into the trachea for the primary purpose of establishing and maintaining a patent airway and to ensure the adequate exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

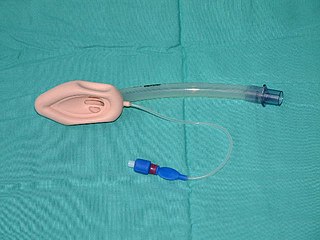

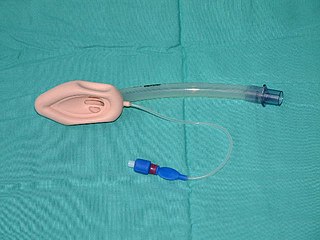

A laryngeal mask airway (LMA), also known as laryngeal mask, is a medical device that keeps a patient's airway open during anaesthesia or while they are unconscious. It is a type of supraglottic airway device. They are most commonly used by anaesthetists to channel oxygen or inhalational anaesthetic to the lungs during surgery and in the pre-hospital setting for unconscious patients.

Airway management includes a set of maneuvers and medical procedures performed to prevent and relieve airway obstruction. This ensures an open pathway for gas exchange between a patient's lungs and the atmosphere. This is accomplished by either clearing a previously obstructed airway; or by preventing airway obstruction in cases such as anaphylaxis, the obtunded patient, or medical sedation. Airway obstruction can be caused by the tongue, foreign objects, the tissues of the airway itself, and bodily fluids such as blood and gastric contents (aspiration).

Respiratory arrest is a sickness caused by apnea or respiratory dysfunction severe enough it will not sustain the body. Prolonged apnea refers to a patient who has stopped breathing for a long period of time. If the heart muscle contraction is intact, the condition is known as respiratory arrest. An abrupt stop of pulmonary gas exchange lasting for more than five minutes may permanently damage vital organs, especially the brain. Lack of oxygen to the brain causes loss of consciousness. Brain injury is likely if respiratory arrest goes untreated for more than three minutes, and death is almost certain if more than five minutes.

Artificial ventilation is a means of assisting or stimulating respiration, a metabolic process referring to the overall exchange of gases in the body by pulmonary ventilation, external respiration, and internal respiration. It may take the form of manually providing air for a person who is not breathing or is not making sufficient respiratory effort, or it may be mechanical ventilation involving the use of a mechanical ventilator to move air in and out of the lungs when an individual is unable to breathe on their own, for example during surgery with general anesthesia or when an individual is in a coma or trauma.

In advanced airway management, rapid sequence induction (RSI) – also referred to as rapid sequence intubation or as rapid sequence induction and intubation (RSII) or as crash induction – is a special process for endotracheal intubation that is used where the patient is at a high risk of pulmonary aspiration. It differs from other techniques for inducing general anesthesia in that several extra precautions are taken to minimize the time between giving the induction drugs and securing the tube, during which period the patient's airway is essentially unprotected.

The arytenoid cartilages are a pair of small three-sided pyramids which form part of the larynx. They are the site of attachment of the vocal cords. Each is pyramidal or ladle-shaped and has three surfaces, a base, and an apex. The arytenoid cartilages allow for movement of the vocal cords by articulating with the cricoid cartilage. They may be affected by arthritis, dislocations, or sclerosis.

An oropharyngeal airway is a medical device called an airway adjunct used in airway management to maintain or open a patient's airway. It does this by preventing the tongue from covering the epiglottis, which could prevent the person from breathing. When a person becomes unconscious, the muscles in their jaw relax and allow the tongue to obstruct the airway.

The Combitube—also known as the esophageal tracheal airway or esophageal tracheal double-lumen airway—is a blind insertion airway device (BIAD) used in the pre-hospital and emergency setting. It is designed to provide an airway to facilitate the mechanical ventilation of a patient in respiratory distress.

Cricoid pressure, also known as the Sellick manoeuvre or Sellick maneuver, is a technique used in endotracheal intubation to try to reduce the risk of regurgitation. The technique involves the application of pressure to the cricoid cartilage at the neck, thus occluding the esophagus which passes directly behind it.

Tracheal intubation, an invasive medical procedure, is the placement of a flexible plastic catheter into the trachea. For millennia, tracheotomy was considered the most reliable method of tracheal intubation. By the late 19th century, advances in the sciences of anatomy and physiology, as well as the beginnings of an appreciation of the germ theory of disease, had reduced the morbidity and mortality of this operation to a more acceptable rate. Also in the late 19th century, advances in endoscopic instrumentation had improved to such a degree that direct laryngoscopy had finally become a viable means to secure the airway by the non-surgical orotracheal route. Nasotracheal intubation was not widely practiced until the early 20th century. The 20th century saw the transformation of the practices of tracheotomy, endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation from rarely employed procedures to essential components of the practices of anesthesia, critical care medicine, emergency medicine, gastroenterology, pulmonology and surgery.

Airtraq is a fibreoptic intubation device used for indirect tracheal intubation in difficult airway situations. It is designed to enable a view of the glottic opening without aligning the oral with the pharyngeal, and laryngeal axes as an advantage over direct endotracheal intubation and allows for intubation with minimal head manipulation and positioning.

A double-lumen endotracheal tube is a type of endotracheal tube which is used in tracheal intubation during thoracic surgery and other medical conditions to achieve selective, one-sided ventilation of either the right or the left lung.

An bronchial blocker is a device which can be inserted down a tracheal tube after tracheal intubation so as to block off the right or left main bronchus of the lungs in order to be able to achieve a controlled one sided ventilation of the lungs in thoracic surgery. The lung tissue distal to the obstruction will collapse, thus allowing the surgeon's view and access to relevant structures within the thoracic cavity.

Advanced airway management is the subset of airway management that involves advanced training, skill, and invasiveness. It encompasses various techniques performed to create an open or patent airway – a clear path between a patient's lungs and the outside world.

Intubation granuloma is a benign growth of granulation tissue in the larynx or trachea, which arises from tissue trauma due to endotracheal intubation. This medical condition is described as a common late complication of tracheal intubation, specifically caused by irritation to the mucosal tissue of the airway during insertion or removal of the patient’s intubation tube.