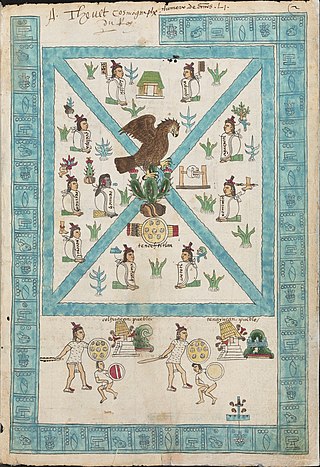

The codex was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term codex is often used for ancient manuscript books, with handwritten contents. A codex, much like the modern book, is bound by stacking the pages and securing one set of edges by a variety of methods over the centuries, yet in a form analogous to modern bookbinding. Modern books are divided into paperback and those bound with stiff boards, called hardbacks. Elaborate historical bindings are called treasure bindings. At least in the Western world, the main alternative to the paged codex format for a long document was the continuous scroll, which was the dominant form of document in the ancient world. Some codices are continuously folded like a concertina, in particular the Maya codices and Aztec codices, which are actually long sheets of paper or animal skin folded into pages.

The Madrid Codex is one of three surviving pre-Columbian Maya books dating to the Postclassic period of Mesoamerican chronology. A fourth codex, named the Grolier Codex, was discovered in 1965. The Madrid Codex is held by the Museo de América in Madrid and is considered to be the most important piece in its collection. However, the original is not on display due to its fragility; an accurate reproduction is displayed in its stead. At one point in time the codex was split into two pieces, given the names "Codex Troano" and "Codex Cortesianus". In the 1880s, Leon de Rosny, an ethnologist, realised that the two pieces belonged together, and helped combine them into a single text. This text was subsequently brought to Madrid, and given the name "Madrid Codex", which remains its most common name today.

Maya codices are folding books written by the pre-Columbian Maya civilization in Maya hieroglyphic script on Mesoamerican bark paper. The folding books are the products of professional scribes working under the patronage of deities such as the Tonsured Maize God and the Howler Monkey Gods. Most of the codices were destroyed by conquistadors and Catholic priests in the 16th century. The codices have been named for the cities where they eventually settled. The Dresden codex is generally considered the most important of the few that survive.

The Dresden Codex is a Maya book, which was believed to be the oldest surviving book written in the Americas, dating to the 11th or 12th century. However, in September 2018 it was proven that the Maya Codex of Mexico, previously known as the Grolier Codex, is, in fact, older by about a century. The codex was rediscovered in the city of Dresden, Germany, hence the book's present name. It is located in the museum of the Saxon State Library. The codex contains information relating to astronomical and astrological tables, religious references, seasons of the earth, and illness and medicine. It also includes information about conjunctions of planets and moons.

The Paris Codex is one of four surviving generally accepted pre-Columbian Maya books dating to the Postclassic Period of Mesoamerican chronology. The document is very poorly preserved and has suffered considerable damage to the page edges, resulting in the loss of some of the text. The codex largely relates to a cycle of thirteen 20-year kʼatuns and includes details of Maya astronomical signs.

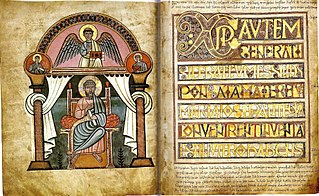

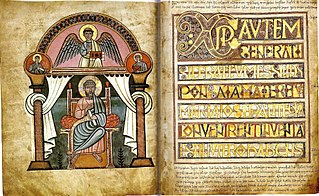

The Stockholm Codex Aureus is a Gospel book written in the mid-eighth century in Southumbria, probably in Canterbury, whose decoration combines Insular and Italian elements. Southumbria produced a number of important illuminated manuscripts during the eighth and early ninth centuries, including the Vespasian Psalter, the Stockholm Codex Aureus, three Mercian prayer books, the Tiberius Bede and the British Library's Royal Bible.

The Ramírez Codex, not to be confused with the Tovar Codex, is a post-conquest codex from the late 16th century entitled Relación del origen de los indios que hábitan esta Nueva España según sus Historias. The manuscript is named after the Mexican scholar José Fernando Ramírez, who discovered it in 1856 in the convent of San Francisco in Mexico City.

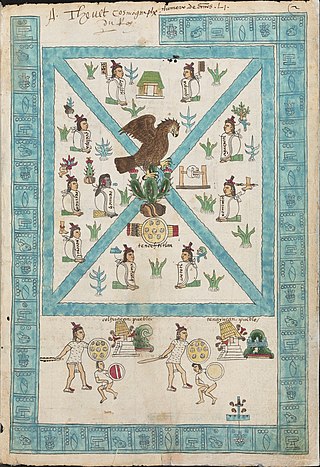

Aztec codices are Mesoamerican manuscripts made by the pre-Columbian Aztec, and their Nahuatl-speaking descendants during the colonial period in Mexico.

Codex Boturini, also known as the Tira de la Peregrinación de los Mexica, is an Aztec codex, which depicts the migration of the Azteca, later Mexica, people from Aztlán. Its date of manufacture is unknown, but likely to have occurred before or just after the Conquest of the Aztec Empire (1519–1521). At least two other Aztec codices have been influenced by the content and style of the Boturini Codex. This Codex has become an insignia of Mexica history and pilgrimage and is carved into a stone wall at the entrance of the National Museum of Anthropology and History in Mexico City.

William Edmond Gates was an American Mayanist. Most of his research focused around Mayan language hieroglyphs. He also collected Mesoamerican manuscripts. Gates studied Mayan based languages like Yucatec Maya, Ch'olti', Huastec and Q'eqchi'. Biographies state that he could speak at least 13 languages. Works and archives related to Gates reside in the collections of Brigham Young University.

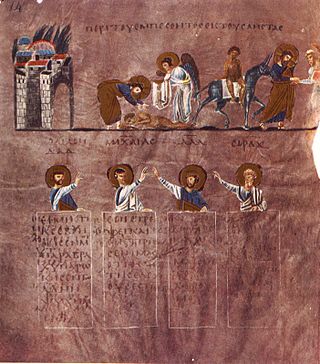

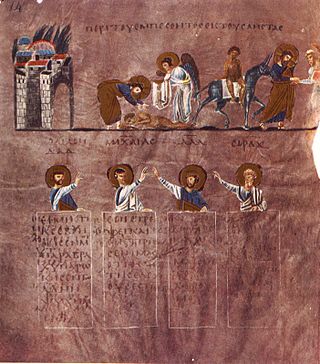

Purple parchment or purple vellum refers to parchment dyed purple; codex purpureus refers to manuscripts written entirely or mostly on such parchment. The lettering may be in gold or silver. Later the practice was revived for some especially grand illuminated manuscripts produced for the emperors in Carolingian art and Ottonian art, in Anglo-Saxon England and elsewhere. Some just use purple parchment for sections of the work; the 8th-century Anglo-Saxon Stockholm Codex Aureus alternates dyed and un-dyed pages.

The Department of Manuscripts and Rare Books of the Austrian National Library in Vienna was formed in April 2008 by merging the departments of "Manuscripts, Autographs, and Closed Collections" and of "Incunabula, Old and Valuable Books".

The Codex Vindobonensis Lat. 1235, designated by i or 17, is a 6th-century Latin Gospel Book. The manuscript contains 142 folios. The text, written on purple dyed vellum in silver ink, is a version of the old Latin. The Gospels follow in the Western order.

Johannes Engebretsen Belsheim was a Norwegian teacher, priest, translator and biographer.

The Codex Vindobonensis 751, also known as the Vienna Boniface Codex, is a ninth-century codex comprising four different manuscripts, the first of which is one of the earliest remaining collections of the correspondence of Saint Boniface. The codex is held in the Austrian National Library in Vienna.

The Maya Codex of Mexico (MCM) is a Maya screenfold codex manuscript of a pre-Columbian type. Long known as the Grolier Codex or Sáenz Codex, in 2018 it was officially renamed the Códice Maya de México (CMM) by the National Institute of Anthropology and History of Mexico. It is one of only four known extant Maya codices, and the only one that still resides in the Americas.

Codex Chimalpopoca or Códice Chimalpopoca is a postconquest cartographic Aztec codex which is officially listed as being in the collection of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia located in Mexico City under "Collección Antiguo no. 159". It is best known for its stories of the hero-god Quetzalcoatl. The current whereabouts of the codex are unknown. It appears to have been lost in the mid-twentieth century. Study of the codex is therefore necessarily provided only through copies and photographs. The codex consists of three parts, two of which are more important, one that regards the pre-Hispanic history of Central Mexico, the Anales de Cuauhtitlan and the other that regards the study of Aztec cosmology, the Leyenda de los Soles.

Maya astronomy is the study of the Moon, planets, Milky Way, Sun, and astronomical phenomena by the Precolumbian Maya Civilization of Mesoamerica. The Classic Maya in particular developed some of the most accurate pre-telescope astronomy in the world, aided by their fully developed writing system and their positional numeral system, both of which are fully indigenous to Mesoamerica. The Classic Maya understood many astronomical phenomena: for example, their estimate of the length of the synodic month was more accurate than Ptolemy's, and their calculation of the length of the tropical solar year was more accurate than that of the Spanish when the latter first arrived. Many temples from the Maya architecture have features oriented to celestial events.

Conservation and restoration of Mesoamerican codices is the process of analyzing, preserving, and treating codices for future study and access. It is a decision-making process that aims to establish the best possible methods and tools of preservation and treatment. The conservation-restoration of Mesoamerican literature is essential for understanding the ancient civilizations of Mexico. Efforts of restoration have proved difficult due to their fragility and importance of preserving historical and evidential value. Non-invasive technologies have been a more recent advancement, making analysis and treatment of pre-Hispanic codices a delayed process. As analysis continues, digitization has also been a more recent and valuable means of making information accessible to a wider audience, thus contributing to further research and preservation.

Mesoamerican codices are manuscripts that present traits of the Mesoamerican indigenous pictoric tradition, either in content, style, or in regards to their symbolic conventions. The unambiguous presence of Mesoamerican writing systems in some of these documents is also an important, but not defining, characteristic, for Mesoamerican codices can comprise pure pictorials, native cartographies with no traces of glyphs on them, or colonial alphabetic texts with indigenous illustrations. Perhaps the best-known examples among such documents are Aztec codices, Maya codices, and Mixtec codices, but other cultures such as the Tlaxcaltec, the Purépecha, the Otomi, the Zapotecs, and the Cuicatecs, are creators of equally relevant manuscripts.