Related Research Articles

Long-term memory (LTM) is the stage of the Atkinson–Shiffrin memory model in which informative knowledge is held indefinitely. It is defined in contrast to sensory memory, the initial stage, and short-term or working memory, the second stage, which persists for about 18 to 30 seconds. LTM is grouped into two categories known as explicit memory and implicit memory. Explicit memory is broken down into episodic and semantic memory, while implicit memory includes procedural memory and emotional conditioning.

Short-term memory is the capacity for holding a small amount of information in an active, readily available state for a short interval. For example, short-term memory holds a phone number that has just been recited. The duration of short-term memory is estimated to be on the order of seconds. The commonly cited capacity of 7 items, found in Miller's Law, has been superseded by 4±1 items. In contrast, long-term memory holds information indefinitely.

Working memory is a cognitive system with a limited capacity that can hold information temporarily. It is important for reasoning and the guidance of decision-making and behavior. Working memory is often used synonymously with short-term memory, but some theorists consider the two forms of memory distinct, assuming that working memory allows for the manipulation of stored information, whereas short-term memory only refers to the short-term storage of information. Working memory is a theoretical concept central to cognitive psychology, neuropsychology, and neuroscience.

"The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on Our Capacity for Processing Information" is one of the most highly cited papers in psychology. It was written by the cognitive psychologist George A. Miller of Harvard University's Department of Psychology and published in 1956 in Psychological Review. It is often interpreted to argue that the number of objects an average human can hold in short-term memory is 7 ± 2. This has occasionally been referred to as Miller's law.

The interference theory is a theory regarding human memory. Interference occurs in learning. The notion is that memories encoded in long-term memory (LTM) are forgotten and cannot be retrieved into short-term memory (STM) because either memory could interfere with the other. There is an immense number of encoded memories within the storage of LTM. The challenge for memory retrieval is recalling the specific memory and working in the temporary workspace provided in STM. Retaining information regarding the relevant time of encoding memories into LTM influences interference strength. There are two types of interference effects: proactive and retroactive interference.

The Decay theory is a theory that proposes that memory fades due to the mere passage of time. Information is therefore less available for later retrieval as time passes and memory, as well as memory strength, wears away. When an individual learns something new, a neurochemical "memory trace" is created. However, over time this trace slowly disintegrates. Actively rehearsing information is believed to be a major factor counteracting this temporal decline. It is widely believed that neurons die off gradually as we age, yet some older memories can be stronger than most recent memories. Thus, decay theory mostly affects the short-term memory system, meaning that older memories are often more resistant to shocks or physical attacks on the brain. It is also thought that the passage of time alone cannot cause forgetting, and that decay theory must also take into account some processes that occur as more time passes.

The Atkinson–Shiffrin model is a model of memory proposed in 1968 by Richard Atkinson and Richard Shiffrin. The model asserts that human memory has three separate components:

- a sensory register, where sensory information enters memory,

- a short-term store, also called working memory or short-term memory, which receives and holds input from both the sensory register and the long-term store, and

- a long-term store, where information which has been rehearsed in the short-term store is held indefinitely.

Serial-position effect is the tendency of a person to recall the first and last items in a series best, and the middle items worst. The term was coined by Hermann Ebbinghaus through studies he performed on himself, and refers to the finding that recall accuracy varies as a function of an item's position within a study list. When asked to recall a list of items in any order, people tend to begin recall with the end of the list, recalling those items best. Among earlier list items, the first few items are recalled more frequently than the middle items.

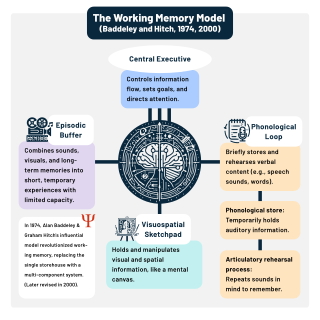

Baddeley's model of working memory is a model of human memory proposed by Alan Baddeley and Graham Hitch in 1974, in an attempt to present a more accurate model of primary memory. Working memory splits primary memory into multiple components, rather than considering it to be a single, unified construct.

Subvocalization, or silent speech, is the internal speech typically made when reading; it provides the sound of the word as it is read. This is a natural process when reading, and it helps the mind to access meanings to comprehend and remember what is read, potentially reducing cognitive load.

The Levels of Processing model, created by Fergus I. M. Craik and Robert S. Lockhart in 1972, describes memory recall of stimuli as a function of the depth of mental processing. More analysis produce more elaborate and stronger memory than lower levels of processing. Depth of processing falls on a shallow to deep continuum. Shallow processing leads to a fragile memory trace that is susceptible to rapid decay. Conversely, deep processing results in a more durable memory trace. There are three levels of processing in this model. Structural processing, or visual, is when we remember only the physical quality of the word. Phonemic processing includes remembering the word by the way it sounds. Lastly, we have semantic processing in which we encode the meaning of the word with another word that is similar or has similar meaning. Once the word is perceived, the brain allows for a deeper processing.

Information processing theory is the approach to the study of cognitive development evolved out of the American experimental tradition in psychology. Developmental psychologists who adopt the information processing perspective account for mental development in terms of maturational changes in basic components of a child's mind. The theory is based on the idea that humans process the information they receive, rather than merely responding to stimuli. This perspective uses an analogy to consider how the mind works like a computer. In this way, the mind functions like a biological computer responsible for analyzing information from the environment. According to the standard information-processing model for mental development, the mind's machinery includes attention mechanisms for bringing information in, working memory for actively manipulating information, and long-term memory for passively holding information so that it can be used in the future. This theory addresses how as children grow, their brains likewise mature, leading to advances in their ability to process and respond to the information they received through their senses. The theory emphasizes a continuous pattern of development, in contrast with cognitive-developmental theorists such as Jean Piaget's theory of cognitive development that thought development occurs in stages at a time.

Memory has the ability to encode, store and recall information. Memories give an organism the capability to learn and adapt from previous experiences as well as build relationships. Encoding allows a perceived item of use or interest to be converted into a construct that can be stored within the brain and recalled later from long-term memory. Working memory stores information for immediate use or manipulation, which is aided through hooking onto previously archived items already present in the long-term memory of an individual.

In psychology and neuroscience, memory span is the longest list of items that a person can repeat back in correct order immediately after presentation on 50% of all trials. Items may include words, numbers, or letters. The task is known as digit span when numbers are used. Memory span is a common measure of working memory and short-term memory. It is also a component of cognitive ability tests such as the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS). Backward memory span is a more challenging variation which involves recalling items in reverse order.

In mental memory, storage is one of three fundamental stages along with encoding and retrieval. Memory is the process of storing and recalling information that was previously acquired. Storing refers to the process of placing newly acquired information into memory, which is modified in the brain for easier storage. Encoding this information makes the process of retrieval easier for the brain where it can be recalled and brought into conscious thinking. Modern memory psychology differentiates between the two distinct types of memory storage: short-term memory and long-term memory. Several models of memory have been proposed over the past century, some of them suggesting different relationships between short- and long-term memory to account for different ways of storing memory.

The modality effect is a term used in experimental psychology, most often in the fields dealing with memory and learning, to refer to how learner performance depends on the presentation mode of studied items.

The irrelevant speech effect (ISE) or irrelevant sound effect is the degradation of serial recall of a list when sounds, especially speech sounds, are presented. This occurs even if the list items are presented visually. The sounds do not need to be a language the participant understands, or even a real language; human speech sounds are sufficient to produce this effect.

The development of memory is a lifelong process that continues through adulthood. Development etymologically refers to a progressive unfolding. Memory development tends to focus on periods of infancy, toddlers, children, and adolescents, yet the developmental progression of memory in adults and older adults is also circumscribed under the umbrella of memory development.

In cognitive psychology, Brown–Peterson task refers to a cognitive exercise designed to test the limits of working memory duration. The task is named for two notable experiments published in the 1950s in which it was first documented, the first by John Brown and the second by husband-and-wife team Lloyd and Margaret Peterson.

Unitary theories of memory are hypotheses that attempt to unify mechanisms of short-term and long-term memory. One can find early contributions to unitary memory theories in the works of John McGeoch in the 1930s and Benton Underwood, Geoffrey Keppel, and Arthur Melton in the 1950s and 1960s. Robert Crowder argued against a separate short-term store starting in the late 1980s. James Nairne proposed one of the first unitary theories, which criticized Alan Baddeley's working memory model, which is the dominant theory of the functions of short-term memory. Other theories since Nairne have been proposed; they highlight alternative mechanisms that the working memory model initially overlooked.

References

- 1 2 3 Goldstein, B. (2011). Cognitive Psychology: Connecting Mind, Research, and Everyday Experience--with coglab manual. (3rd ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

- ↑ Greene, R. L. (1987). "Effects of maintenance rehearsal on human memory". Psychological Bulletin. 102 (3): 403–413. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.102.3.403.

- ↑ Jonides, J.; Lacey, S.C.; Nee, D.E. (2005). "Processes of working memory in mind and brain". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 14: 2–5. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00323.x.

- 1 2 Dempster, Frank N. (1981). "Memory span: Sources of individual and developmental differences". Psychological Bulletin. 89 (1): 63–100. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.89.1.63.

- 1 2 3 4 Nee, E. N.; Askren, M. K.; Berman, M. G.; Demlralp, E.; Krawitz, A.; Jonides, J. (2012). "A meta-analysis of executive components of working memory". Cerebral Cortex. 23 (2): 264–282. doi:10.1093/cercor/bhs007. PMC 3584956 . PMID 22314046.

- 1 2 Baddeley, A.; Eyesneck, M. W.; Anderson, M. C. (2015). Memory. New York: Psychology Press.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Reisberg, D. (1997). Cognition: Exploring the science of the mind. New York: Norton & Co.

- 1 2 Ginns, P. (2005). "Meta-analysis of the modality effect". Learning and Instruction. 15 (4): 313–331. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.001.

- 1 2 Bransford, J. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school (Expanded ed.). Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. p. 94.

- ↑ Garon, N.; Bryson, S.; Smith, I. (2008). "Executive Function in Preschoolers: A Review Using an Integrative Framework". Psychological Bulletin. 134 (1): 31–60. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.1.31.