Long-term memory (LTM) is the stage of the Atkinson–Shiffrin memory model in which informative knowledge is held indefinitely. It is defined in contrast to sensory memory, the initial stage, and short-term or working memory, the second stage, which persists for about 18 to 30 seconds. LTM is grouped into two categories known as explicit memory and implicit memory. Explicit memory is broken down into episodic and semantic memory, while implicit memory includes procedural memory and emotional conditioning.

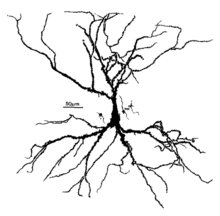

The hippocampus is a major component of the brain of humans and other vertebrates. Humans and other mammals have two hippocampi, one in each side of the brain. The hippocampus is part of the limbic system, and plays important roles in the consolidation of information from short-term memory to long-term memory, and in spatial memory that enables navigation. The hippocampus is located in the allocortex, with neural projections into the neocortex, in humans as well as other primates. The hippocampus, as the medial pallium, is a structure found in all vertebrates. In humans, it contains two main interlocking parts: the hippocampus proper, and the dentate gyrus.

In neurology, anterograde amnesia is the inability to create new memories after an event that caused amnesia, leading to a partial or complete inability to recall the recent past, while long-term memories from before the event remain intact. This is in contrast to retrograde amnesia, where memories created prior to the event are lost while new memories can still be created. Both can occur together in the same patient. To a large degree, anterograde amnesia remains a mysterious ailment because the precise mechanism of storing memories is not yet well understood, although it is known that the regions of the brain involved are certain sites in the temporal cortex, especially in the hippocampus and nearby subcortical regions.

The fornix is a C-shaped bundle of nerve fibers in the brain that acts as the major output tract of the hippocampus. The fornix also carries some afferent fibers to the hippocampus from structures in the diencephalon and basal forebrain. The fornix is part of the limbic system. While its exact function and importance in the physiology of the brain are still not entirely clear, it has been demonstrated in humans that surgical transection—the cutting of the fornix along its body—can cause memory loss. There is some debate over what type of memory is affected by this damage, but it has been found to most closely correlate with recall memory rather than recognition memory. This means that damage to the fornix can cause difficulty in recalling long-term information such as details of past events, but it has little effect on the ability to recognize objects or familiar situations.

In cognitive psychology and neuroscience, spatial memory is a form of memory responsible for the recording and recovery of information needed to plan a course to a location and to recall the location of an object or the occurrence of an event. Spatial memory is necessary for orientation in space. Spatial memory can also be divided into egocentric and allocentric spatial memory. A person's spatial memory is required to navigate in a familiar city. A rat's spatial memory is needed to learn the location of food at the end of a maze. In both humans and animals, spatial memories are summarized as a cognitive map.

In neurology, retrograde amnesia (RA) is the inability to access memories or information from before an injury or disease occurred. RA differs from a similar condition called anterograde amnesia (AA), which is the inability to form new memories following injury or disease onset. Although an individual can have both RA and AA at the same time, RA can also occur on its own; this 'pure' form of RA can be further divided into three types: focal, isolated, and pure RA. RA negatively affects an individual's episodic, autobiographical, and declarative memory, but they can still form new memories because RA leaves procedural memory intact. Depending on its severity, RA can result in either temporally graded or more permanent memory loss. However, memory loss usually follows Ribot's law, which states that individuals are more likely to lose recent memories than older memories. Diagnosing RA generally requires using an Autobiographical Memory Interview (AMI) and observing brain structure through magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), a computed tomography scan (CT), or electroencephalography (EEG).

Explicit memory is one of the two main types of long-term human memory, the other of which is implicit memory. Explicit memory is the conscious, intentional recollection of factual information, previous experiences, and concepts. This type of memory is dependent upon three processes: acquisition, consolidation, and retrieval.

Acamprosate, sold under the brand name Campral, is a medication which reduces alcoholism cravings. It is thought to stabilize chemical signaling in the brain that would otherwise be disrupted by alcohol withdrawal. When used alone, acamprosate is not an effective therapy for alcohol use disorder in most individuals, as it only addresses withdrawal symptoms and not psychological dependence. It facilitates a reduction in alcohol consumption as well as full abstinence when used in combination with psychosocial support or other drugs that address the addictive behavior.

A drug-related blackout is a phenomenon caused by the intake of any substance or medication in which short-term and long-term memory creation is impaired, therefore causing a complete inability to recall the past. Blackouts are frequently described as having effects similar to that of anterograde amnesia, in which the subject cannot recall any events after the event that caused amnesia.

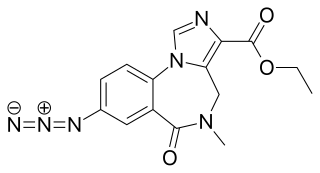

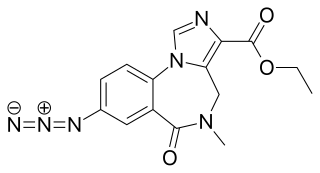

Ro15-4513 is a weak partial inverse agonist of the benzodiazepine class of drugs, developed by Hoffmann–La Roche in the 1980s. It acts as an inverse agonist, and can therefore be an antidote to the acute impairment caused by alcohols, including ethanol, isopropanol, tert-butyl alcohol, tert-amyl alcohol, 3-methyl-3-pentanol, methylpentynol, and ethchlorvynol.

Memory and trauma is the deleterious effects that physical or psychological trauma has on memory.

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome (AWS) is a set of symptoms that can occur following a reduction in alcohol use after a period of excessive use. Symptoms typically include anxiety, shakiness, sweating, vomiting, fast heart rate, and a mild fever. More severe symptoms may include seizures, and delirium tremens (DTs); which can be fatal in untreated patients. Symptoms start at around 6 hours after last drink. Peak incidence of seizures occurs at 24-36 hours and peak incidence of delirium tremens is at 48-72 hours.

The short-term effects of alcohol consumption range from a decrease in anxiety and motor skills and euphoria at lower doses to intoxication (drunkenness), to stupor, unconsciousness, anterograde amnesia, and central nervous system depression at higher doses. Cell membranes are highly permeable to alcohol, so once it is in the bloodstream, it can diffuse into nearly every cell in the body.

Memory consolidation is a category of processes that stabilize a memory trace after its initial acquisition. A memory trace is a change in the nervous system caused by memorizing something. Consolidation is distinguished into two specific processes. The first, synaptic consolidation, which is thought to correspond to late-phase long-term potentiation, occurs on a small scale in the synaptic connections and neural circuits within the first few hours after learning. The second process is systems consolidation, occurring on a much larger scale in the brain, rendering hippocampus-dependent memories independent of the hippocampus over a period of weeks to years. Recently, a third process has become the focus of research, reconsolidation, in which previously consolidated memories can be made labile again through reactivation of the memory trace.

Kindling due to substance withdrawal is the neurological condition which results from repeated withdrawal episodes from sedative–hypnotic drugs such as alcohol and benzodiazepines.

Memory improvement is the act of enhancing one's memory. Factors motivating research on improving memory include conditions such as amnesia, age-related memory loss, people’s desire to enhance their memory, and the search to determine factors that impact memory and cognition. There are different techniques to improve memory, some of which include cognitive training, psychopharmacology, diet, stress management, and exercise. Each technique can improve memory in different ways.

The effects of stress on memory include interference with a person's capacity to encode memory and the ability to retrieve information. Stimuli, like stress, improved memory when it was related to learning the subject. During times of stress, the body reacts by secreting stress hormones into the bloodstream. Stress can cause acute and chronic changes in certain brain areas which can cause long-term damage. Over-secretion of stress hormones most frequently impairs long-term delayed recall memory, but can enhance short-term, immediate recall memory. This enhancement is particularly relative in emotional memory. In particular, the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and the amygdala are affected. One class of stress hormone responsible for negatively affecting long-term, delayed recall memory is the glucocorticoids (GCs), the most notable of which is cortisol. Glucocorticoids facilitate and impair the actions of stress in the brain memory process. Cortisol is a known biomarker for stress. Under normal circumstances, the hippocampus regulates the production of cortisol through negative feedback because it has many receptors that are sensitive to these stress hormones. However, an excess of cortisol can impair the ability of the hippocampus to both encode and recall memories. These stress hormones are also hindering the hippocampus from receiving enough energy by diverting glucose levels to surrounding muscles.

Memory is the faculty of the mind by which data or information is encoded, stored, and retrieved when needed. It is the retention of information over time for the purpose of influencing future action. If past events could not be remembered, it would be impossible for language, relationships, or personal identity to develop. Memory loss is usually described as forgetfulness or amnesia.

The long-term impact of alcohol on the brain has become a growing area of research focus. While researchers have found that moderate alcohol consumption in older adults is associated with better cognition and well-being than abstinence, excessive alcohol consumption is associated with widespread and significant brain lesions. Other data – including investigated brain-scans of 36,678 UK Biobank participants – suggest that even "light" or "moderate" consumption of alcohol by itself harms the brain, such as by reducing brain grey matter volume. This may imply that alternatives and generally aiming for lowest possible consumption could usually be the advisable approach.

The hippocampus participates in the encoding, consolidation, and retrieval of memories. The hippocampus is located in the medial temporal lobe (subcortical), and is an infolding of the medial temporal cortex. The hippocampus plays an important role in the transfer of information from short-term memory to long-term memory during encoding and retrieval stages. These stages do not need to occur successively, but are, as studies seem to indicate, and they are broadly divided in the neuronal mechanisms that they require or even in the hippocampal areas that they seem to activate. According to Gazzaniga, "encoding is the processing of incoming information that creates memory traces to be stored." There are two steps to the encoding process: "acquisition" and "consolidation". During the acquisition process, stimuli are committed to short term memory. Then, consolidation is where the hippocampus along with other cortical structures stabilize an object within long term memory, which strengthens over time, and is a process for which a number of theories have arisen to explain the underlying mechanism. After encoding, the hippocampus is capable of going through the retrieval process. The retrieval process consists of accessing stored information; this allows learned behaviors to experience conscious depiction and execution. Encoding and retrieval are both affected by neurodegenerative and anxiety disorders and epilepsy.