The jaguar is a large cat species and the only living member of the genus Panthera native to the Americas. With a body length of up to 1.85 m and a weight of up to 158 kg (348 lb), it is the biggest cat species in the Americas and the third largest in the world. Its distinctively marked coat features pale yellow to tan colored fur covered by spots that transition to rosettes on the sides, although a melanistic black coat appears in some individuals. The jaguar's powerful bite allows it to pierce the carapaces of turtles and tortoises, and to employ an unusual killing method: it bites directly through the skull of mammalian prey between the ears to deliver a fatal blow to the brain.

A black panther is the melanistic colour variant of the leopard and the jaguar. Black panthers of both species have excess black pigments, but their typical rosettes are also present. They have been documented mostly in tropical forests, with black leopards in Africa and Asia, and black jaguars in South America. Melanism is caused by a recessive allele in the leopard, and by a dominant allele in the jaguar.

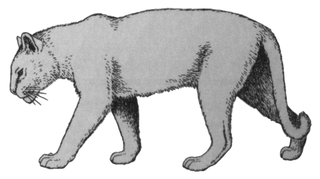

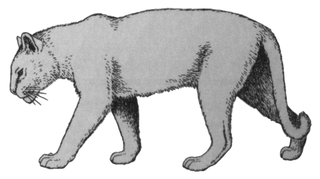

The cougar, also known as the puma, mountain lion, catamount or panther, is a large cat native to the Americas, second only in size to the stockier jaguar. They are not technically grouped with the "true" big cats, as they are slightly smaller than other big cats, and they lack the vocal physiology to roar. Its range spans from the Canadian Provinces of the Yukon, British Columbia and Alberta, the Rocky Mountains and areas to the Western United States. Their range extends further south through Mexico, where they are found in nearly every state, to the Amazon Rainforest and the southern Andes Mountains in Patagonia. The puma inhabits every mainland country in Central and South America, making it the most widely distributed large, wild, terrestrial mammal in the Western Hemisphere, and one of the most widespread on planet Earth. It is an adaptable, generalist species, occurring in most American habitat types. It prefers habitats with dense underbrush and rocky areas for stalking but also lives in open areas.

The term "big cat" is typically used to refer to any of the five living members of the genus Panthera, namely the tiger, lion, jaguar, leopard, and snow leopard, as well as the non-pantherine cheetah and cougar.

Species reintroduction is the deliberate release of a species into the wild, from captivity or other areas where the organism is capable of survival. The goal of species reintroduction is to establish a healthy, genetically diverse, self-sustaining population to an area where it has been extirpated, or to augment an existing population. Species that may be eligible for reintroduction are typically threatened or endangered in the wild. However, reintroduction of a species can also be for pest control; for example, wolves being reintroduced to a wild area to curb an overpopulation of deer. Because reintroduction may involve returning native species to localities where they had been extirpated, some prefer the term "reestablishment".

The fisher is a small carnivorous mammal native to North America, a forest-dwelling creature whose range covers much of the boreal forest in Canada to the northern United States. It is a member of the mustelid family, and is in the monospecific genus Pekania. It is sometimes misleadingly referred to as a fisher cat, even though it is not a cat.

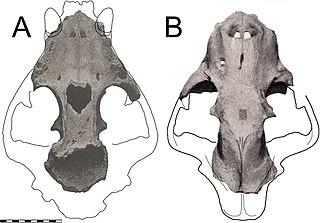

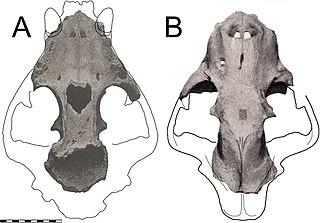

Panthera atrox, better known as the American lion, also called the North American lion, or American cave lion, is an extinct pantherine cat. Panthera atrox lived in North America during the late Pleistocene epoch and the early Holocene epoch, from around 340,000 to 11,000 years ago. The species was initially described by American paleontologist Joseph Leidy in 1853 based on a fragmentary mandible (jawbone) from Mississippi; the name means "savage" or "cruel". The status of the species is debated, with some mammalogists and paleontologists considering it a distinct species or a subspecies of Panthera leo, which contains living lions. However, novel genetic evidence has shown that it is instead from a sister lineage with the cave lion, evolving after its geographic separation. Its fossils have been excavated from Alaska to Mexico. It was about 25% larger than the modern lion, making it one of the largest known felids.

The Mexican wolf, also known as the lobo, is a subspecies of gray wolf native to southeastern Arizona and southern New Mexico in the United States, and northern Mexico. It once also ranged into western Texas. It is the smallest of North America's gray wolves, and is similar to the Great Plains wolf, though it is distinguished by its smaller, narrower skull and its darker pelt, which is yellowish-gray and heavily clouded with black over the back and tail. Its ancestors were likely the first gray wolves to enter North America after the extinction of the Beringian wolf, as indicated by its southern range and basal physical and genetic characteristics.

Pantherinae is a subfamily within the family Felidae; it was named and first described by Reginald Innes Pocock in 1917 as only including the Panthera species. The Pantherinae genetically diverged from a common ancestor between 9.32 to 4.47 million years ago and 10.67 to 3.76 million years ago.

The North American cougar is a cougar subspecies in North America. It is the biggest cat in North America, even larger than North American jaguars. It was once common in eastern North America before widespread persecution and hunting led to its extirpation there, and is still prevalent in the western half of the continent. This subspecies includes populations in western Canada, the western United States, Florida, Mexico and Central America, and possibly South America northwest of the Andes Mountains. It thus includes the extirpated eastern cougar and extant Florida panther populations.

Panthera gombaszoegensis, also known as the European jaguar, is a Panthera species that lived from about 2.0 to 0.35 million years ago in Europe. The first fossils were excavated in 1938 in Gombasek, Slovakia.

Panthera onca mesembrina is an extinct subspecies of jaguar that was endemic to Patagonia in southern South America during the late Pleistocene epoch. It is known from several fragmentary specimens, the first of which found was in 1899 at "Cueva del Milodon" in Chile. These fossils were referred to a new genus and species "Iemish listai" by naturalist Santiago Roth, who thought they might be the bones of the mythological iemisch of Tehuelche folklore. A later expedition recovered more bones, including the skull of a large male that was described in detail by Angel Cabrera in 1934. Cabrera created a new name for the giant felid remains, Panthera onca mesembrina, after realizing that its fossils were near-identical to modern jaguars’. P. onca mesembrina's validity is disputed, with some paleontologists suggesting that it is a synonym of Panthera atrox.

Panthera onca augusta is an extinct subspecies of the jaguar that was endemic to North America during the Pleistocene epoch.

Buenos Aires National Wildlife Refuge provides 117,107 acres (47,392 ha) of habitat for threatened and endangered plants and animals. This refuge, in Pima County, Arizona, was established in 1985.

Panthera Corporation, or Panthera, is a charitable organization devoted to preserving wild cats and their ecosystems around the globe. Founded in 2006, Panthera is devoted to the conservation of the world’s 40 species of wild cats and the vast ecosystems they inhabit. Their team of biologists, data scientists, law enforcement experts and wild cat advocates studies and protects the seven species of big cats: cheetahs, jaguars, leopards, lions, pumas, snow leopards and tigers. Panthera also creates targeted conservation strategies for the world’s most threatened and overlooked small cats, such as fishing cats, ocelots and Andean cats. The organization has offices in New York City and Europe, as well as offices in Mesoamerica, South America, Africa and Asia.

The Amur leopard is a leopard subspecies native to the Primorye region of southeastern Russia and northern China. It is listed as Critically Endangered on the IUCN Red List, as in 2007, only 19–26 wild leopards were estimated to survive in southeastern Russia and northeastern China.

Many different species of mammal can be classified as cats (felids) in the United States. These include domestic cat, of the species Felis catus; medium-sized wild cats from the genus Lynx; and big cats from the genera Puma and Panthera. Domestic cats vastly outnumber wild cats in the United States.

El Jefe is an adult, male jaguar that was seen in Arizona. He was first recorded in the Whetstone Mountains in November 2011, and was later photographed over several years in the Santa Rita Mountains. From November 2011 to late 2015, El Jefe was the only wild jaguar verified to live in the United States since the death of Arizona Jaguar Macho B in 2009. According to "Notes on the Occurrences of Jaguars in Arizona and New Mexico", an article regarding jaguars in the Southwest US, "Sixty two jaguars have been reportedly killed or captured in the American Southwest since 1900." He was not seen in Arizona after September 2015 and it was presumed that he returned to Mexico, where the nearest breeding population of jaguars is located. This was confirmed almost seven years later in August 2022, when a collective of conservation groups announced that he had been photographed using a motion-detecting camera, on November 27, 2021, in the central part of the state of Sonora.

The South American jaguar is a jaguar population in South America. Though a number of subspecies of jaguar have been proposed for South America, morphological and genetic research did not reveal any evidence for subspecific differentiation.