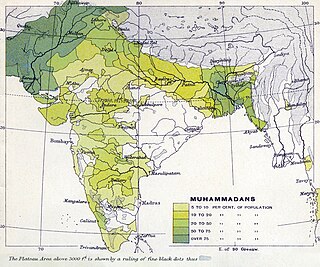

Opposition to the Partition of India was widespread in British India in the 20th century and it continues to remain a talking point in South Asian politics. Those who opposed it often adhered to the doctrine of composite nationalism in the Indian subcontinent. [3] The Hindu, Christian, Anglo-Indian, Parsi and Sikh communities were largely opposed to the Partition of India (and its underlying two-nation theory), [4] [5] [6] [7] as were many Muslims (these were represented by the All India Azad Muslim Conference). [8] [9] [10]

Contents

- Organisations and prominent individuals opposing the partition of India

- Political parties

- Politicians

- Military officers

- Historians and other academics

- Scientists

- Writers

- Religious leaders and organizations

- Indian Reunification proposals

- See also

- References

- Cited sources

- External links

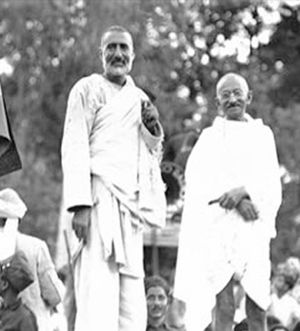

Pashtun politician and Indian independence activist Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan of the Khudai Khidmatgar viewed the proposal to partition India as un-Islamic and contradicting a common history in which Muslims considered India as their homeland for over a millennium. [1] Mahatma Gandhi opined that "Hindus and Muslims were sons of the same soil of India; they were brothers who therefore must strive to keep India free and united." [2]

Sunni Muslims of the Deobandi school of thought regarded the proposed partition and formation of a separate, majority Muslim nation state (i.e. the future Pakistan) as a "conspiracy of the colonial government to prevent the emergence of a strong united India". Deobandis therefore helped to organize the Azad Muslim Conference, to condemn the partition of India. [11] They also argued that the economic development of Muslims would be hurt if India was partitioned, [11] seeing the idea of partition as one that was designed to keep Muslims backward. [12] They also expected "Muslim-majority provinces in united India to be more effective than the rulers of independent Pakistan in helping the Muslim minorities living in Hindu-majority areas." [11] Deobandis pointed to the Treaty of Hudaybiyyah, which was made between the Muslims and Qureysh of Mecca, that "promoted mutual interaction between the two communities thus allowing more opportunities for Muslims to preach their religion to Qureysh through peaceful tabligh." [11] Deobandi Sunni scholar Sayyid Husain Ahmad Madani argued for a united India in his book Muttahida Qaumiyat Aur Islam (Composite Nationalism and Islam), promulgating the idea that different religions do not constitute different nationalities and that the proposition for a partition of India was not justifiable, religiously. [13]

Khaksar Movement leader Allama Mashriqi opposed the partition of India because he felt that if Muslims and Hindus had largely lived peacefully together in India for centuries, they could also do so in a free and united India. He reasoned that a division of India along religious lines would breed fundamentalism and extremism on both sides of the border. Mashriqi thought that "Muslim majority areas were already under Muslim rule, so if any Muslims wanted to move to these areas, they were free to do so without having to divide the country." To him, separatist leaders "were power hungry and misleading Muslims in order to bolster their own power by serving the British agenda." [14] All of Hindustan, according to Mashriqi, belonged to Indian Muslims. [15]

In 1941, a CID report states that thousands of Muslim weavers under the banner of Momin Conference and coming from Bihar and Eastern U.P. descended in Delhi demonstrating against the proposed two-nation theory. A gathering of more than fifty thousand people from an unorganized sector was not usual at that time, so its importance should be duly recognized. The non-ashraf Muslims constituting a majority of Indian Muslims were opposed to partition but sadly they were not heard. They were firm believers of Islam yet they were opposed to Pakistan. [16]

In the 1946 Indian provincial elections, the Muslim League got the support mostly from Ashrafs, the upper class Muslims. [17] Lower class Indian Muslims opposed the partition of India, believing that "a Muslim state would benefit only upper-class Muslims." [18]

The All India Conference of Indian Christians, representing the Christians of colonial India, along with Sikh political parties such as the Chief Khalsa Diwan and Shiromani Akali Dal led by Master Tara Singh condemned the call by separatists to create Pakistan, viewing it as a movement that would possibly persecute them. [5] [6] Frank Anthony, a Christian leader who served as the president of the All India Anglo-Indian Association cited several reasons for opposing the partition of India. [19] If India were to be divided, the regions proposed to become Pakistan would still contain a “considerable number of non-Muslims, and a large number of Muslims would also remain in [independent] India" thus rendering the partition to be useless. [19] Furthermore, the partition of India would jeopardise the interests of the minority communities. [20] He held that the plan proposed by the All India Muslim League would cause the balkanization of India that would lead to "potentially ‘emasculating’ India" as a global leader. [19] Anthony stated that India was unlike Europe in that “India had achieved a basic ethnic and cultural unity.” [19] Lastly, Anthony held that “the division of India would lead to war between the two countries” and give rise to the spread of extremist ideologies. [19]

Critics of the partition of India argue that an undivided India would have boasted one of the strongest armies in the world, had more competitive sports teams, fostered an increased protection of minorities with religious harmony, championed greater women's rights, possessed extended maritime borders, projected elevated soft power, and offered a "focus on education and health instead of the defence sector". [21]

Pakistan was created through the partition of India on the basis of religious segregation; [22] the very concept of dividing the country of India has criticized for its implication "that people with different backgrounds" cannot live together. [23] After it occurred, critics of the partition of India point to the displacement of fifteen million people, the murder of more than one million people, and the rape of 75,000 women to demonstrate the view that it was a mistake. [24]