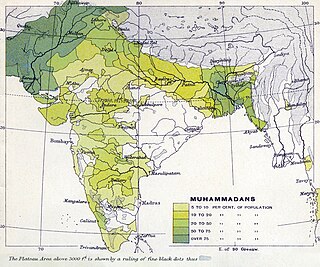

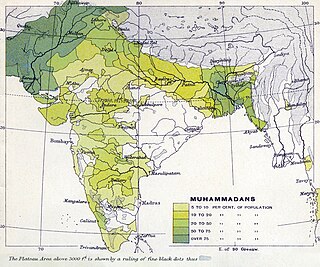

The partition of India in 1947 was the division of British India into two independent dominion states, the Union of India and Dominion of Pakistan. The Union of India is today the Republic of India and the Dominion of Pakistan, the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, and the People's Republic of Bangladesh. The partition involved the division of two provinces, Bengal and the Punjab, based on district-wise Hindu or Muslim majorities. It also involved the division of the British Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Indian Civil Service, the railways, and the central treasury, between the two new dominions. The partition was set forth in the Indian Independence Act 1947 and resulted in the dissolution of the British Raj, or Crown rule in India. The two self-governing countries of India and Pakistan legally came into existence at midnight on 14–15 August 1947.

The All-India Muslim League (AIML), simply called the Muslim League, was a political party established in Dhaka in 1906 when some well-known Muslim politicians met the Viceroy of India, Lord Minto, with the goal of securing Muslim interests in British India.

The Pakistan Movement emerged in the early 20th century as part of a campaign that advocated the creation of an Islamic state in parts of what was then British India. It was rooted in the two-nation theory, which asserted that Indian Muslims were fundamentally and irreconcilably distinct from Indian Hindus and would therefore require separate self-determination upon the decolonization of India. The idea was largely realized when the All-India Muslim League ratified the Lahore Resolution on 23 March 1940, calling for the Muslim-majority regions of the Indian subcontinent to be "grouped to constitute independent states" that would be "autonomous and sovereign" with the aim of securing Muslim socio-political interests vis-à-vis the Hindu majority. It was in the aftermath of the Lahore Resolution that, under the aegis of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the cause of "Pakistan" became widely popular among the Muslims of the Indian independence movement.

The Khilafat movement (1919–22) was a political campaign launched by Indian Muslims in British India over British policy against Turkey and the planned dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire after World War I by Allied forces.

Direct Action Day was the day the All-India Muslim League decided to take a "direct action" using general strikes and economic shut down to demand a separate Muslim homeland after the British exit from India. Also known as the 1946 Calcutta Riots, it soon became a day of communal violence in Calcutta. It led to large-scale violence between Muslims and Hindus in the city of Calcutta in the Bengal province of British India. The day also marked the start of what is known as The Week of the Long Knives. While there is a certain degree of consensus on the magnitude of the killings, including their short-term consequences, controversy remains regarding the exact sequence of events, the various actors' responsibility and the long-term political consequences.

The two-nation theory was an ideology of religious nationalism that advocated Muslim Indian nationhood, with separate homelands for Indian Muslims and Indian Hindus within a decolonised British India, which ultimately led to the partition of India in 1947. Its various descriptions of religious differences were the main factor in Muslim separatist thought in the Indian subcontinent, asserting that Indian Muslims and Indian Hindus are two separate nations, each with their own customs, traditions, art, architecture, literature, interests, and ways of life.

Indian nationalism is an instance of territorial nationalism, which is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, but was fully developed during the Indian independence movement which campaigned for independence from British rule. Indian nationalism quickly rose to popularity in India through these united anti-colonial coalitions and movements. Independence movement figures like Mahatma Gandhi, Subhas Chandra Bose, and Jawaharlal Nehru spearheaded the Indian nationalist movement. After Indian Independence, Nehru and his successors continued to campaign on Indian nationalism in face of border wars with both China and Pakistan. After the Indo-Pakistan War of 1971 and the Bangladesh Liberation War, Indian nationalism reached its post-independence peak. However by the 1980s, religious tensions reached a melting point and Indian nationalism sluggishly collapsed in the following decades. Despite its decline and the rise of religious nationalism, Indian nationalism and its historic figures continue to strongly influence the politics of India and reflect an opposition to the sectarian strands of Hindu nationalism and Muslim nationalism.

The first Partition of Bengal (1905) was a territorial reorganization of the Bengal Presidency implemented by the authorities of the British Raj. The reorganization separated the largely Muslim eastern areas from the largely Hindu western areas. Announced on 20 July 1905 by Lord Curzon, then Viceroy of India, and implemented West Bengal for Hindus and East Bengal for Muslims, it was undone a mere six years later.

The Partition of Bengal in 1947, also known as the Second Partition of Bengal, part of the Partition of India, divided the British Indian Bengal Province along the Radcliffe Line between the Dominion of India and the Dominion of Pakistan. The Bengali Hindu-majority West Bengal became a state of India, and the Bengali Muslim-majority East Bengal became a province of Pakistan.

From a historical perspective, Professor Ishtiaq Ahmed of the University of Stockholm and Professor Shamsul Islam of the University of Delhi classified the Muslims of Colonial India into two categories during the era of the Indian independence movement: nationalist Muslims and Muslim nationalists. The All India Azad Muslim Conference represented nationalist Muslims, while the All-India Muslim League represented the Muslim nationalists. One such popular debate was the Madani–Iqbal debate.

Pakistani nationalism refers to the political, cultural, linguistic, historical, religious and geographical expression of patriotism by the people of Pakistan, of pride in the history, heritage and identity of Pakistan, and visions for its future.

Communal violence is a form of violence that is perpetrated across ethnic or communal lines, where the violent parties feel solidarity for their respective groups and victims are chosen based upon group membership. The term includes conflicts, riots and other forms of violence between communities of different religious faith or ethnic origins.

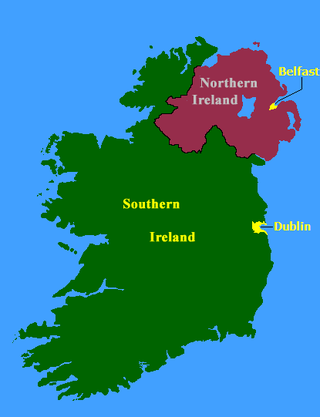

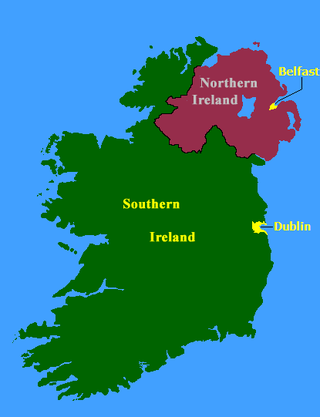

In international relations, a partition is a division of a previously unified territory into two or more parts.

Interactions between Muslims and Hindus began in the 7th century, after the advent of Islam in the Arabian Peninsula. These interactions were mainly by trade throughout the Indian Ocean. Historically, these interactions formed contrasting patterns in northern and southern India. While there is a history of conquest and domination in the north, Hindu-Muslim relations in Kerala and Tamil Nadu have been peaceful. However, historical evidence has shown that violence had existed by the year 1700 A.D.

Religious violence in India includes acts of violence by followers of one religious group against followers and institutions of another religious group, often in the form of rioting. Religious violence in India has generally involved Hindus and Muslims.

Indian reunification refers to the potential reunification of India with Pakistan and Bangladesh, which were partitioned from British India in 1947.

There have been several instances of religious violence against Muslims since the partition of India in 1947, frequently in the form of violent attacks on Muslims by Hindu nationalist mobs that form a pattern of sporadic sectarian violence between the Hindu and Muslim communities. Over 10,000 people have been killed in Hindu-Muslim communal violence since 1950 in 6,933 instances of communal violence between 1954 and 1982.

Opposition to the Partition of India was widespread in British India in the 20th century and it continues to remain a talking point in South Asian politics. Those who opposed it often adhered to the doctrine of composite nationalism in the Indian subcontinent. The Hindu, Christian, Anglo-Indian, Parsi and Sikh communities were largely opposed to the Partition of India, as were many Muslims.

Hindu–Muslim unity is a religiopolitical concept in the Indian subcontinent which stresses members of the two largest faith groups there, Hindus and Muslims, working together for the common good. The concept was championed by various persons, such as leaders in the Indian independence movement, namely Mahatma Gandhi and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, as well as by political parties and movements in British India, such as the Indian National Congress, Khudai Khidmatgar and All India Azad Muslim Conference. Those who opposed the partition of India often adhered to the doctrine of composite nationalism.