Chinese mythology is mythology that has been passed down in oral form or recorded in literature in the geographic area now known as "China". Chinese mythology includes many varied myths from regional and cultural traditions. Chinese mythology is far from monolithic, not being an integrated system, even among just Han people. Chinese mythology is encountered in the traditions of various classes of people, geographic regions, historical periods including the present, and from various ethnic groups. China is the home of many mythological traditions, including that of Han Chinese and their Huaxia predecessors, as well as Tibetan mythology, Turkic mythology, Korean mythology, Japanese mythology and many others. However, the study of Chinese mythology tends to focus upon material in Chinese language.

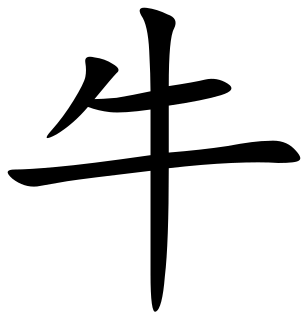

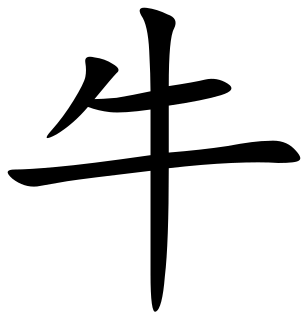

The Ox (牛) is the second of the 12-year periodic sequence (cycle) of animals which appear in the Chinese zodiac related to the Chinese calendar, and also appears in related calendar systems. The Chinese term translated here as ox is in Chinese niú (牛), a word generally referring to cows, bulls, or neutered types of the bovine family, such as common cattle or water buffalo. The zodiacal ox may be construed as male, female, neutered, hermaphroditic, and either singular or plural. The Year of the Ox is also denoted by the Earthly Branch symbol chǒu (丑). The term "zodiac" ultimately derives from an Ancient Greek term referring to a "circle of little animals". There are also a yearly month of the ox and a daily hour of the ox. Years of the oxen (cows) are cyclically differentiated by correlation to the Heavenly Stems cycle, resulting in a repeating cycle of five years of the ox/cow, each ox/cow year also being associated with one of the Chinese wǔxíng, also known as the "five elements", or "phases": the "Five Phases" being Fire, Water, Wood, Metal, and Earth. The Year of the Ox follows after the Year of the Rat which happened in 2020 and it then is followed by the Year of the Tiger, which will happen in 2022.

The Jade Emperor in Chinese culture, traditional religions and myth is one of the representations of the first god. In Daoist theology he is the assistant of Yuanshi Tianzun, who is one of the Three Pure Ones, the three primordial emanations of the Tao. He is also the Cao Đài of Caodaism known as Ngọc Hoàng Thượng đế. He is often identified with Śakra in Chinese Buddhist cosmology. In Korean mythology he is known as Haneullim.

There are varying beliefs about cattle in societies and religions with cows, bulls, and calves being worshiped at various stages of history. As such, numerous peoples throughout the world have at one point in time honored bulls as sacred. In the Sumerian religion, Marduk is the "bull of Utu". In Hinduism, Shiva's steed is Nandi, the Bull. The sacred bull survives in the constellation Taurus. The bull, whether lunar as in Mesopotamia or solar as in India, is the subject of various other cultural and religious incarnations as well as modern mentions in New Age cultures.

Shennong (神農), variously translated as "Divine Farmer" or "Divine Husbandman", was a mythological Chinese ruler who has become a deity in Chinese and Vietnamese folk religion. He is venerated as a culture hero in China and Vietnam.

An ox, also known as a bullock in Australia and India, is a bovine trained as a draft animal. Oxen are commonly castrated adult male cattle; castration makes the animals easier to control. Cows or bulls may also be used in some areas.

Taotie (饕餮) are ancient Chinese mythological creatures that were commonly emblazoned on bronze and other artifacts during the 1st millennium BC. Taotie are one of the "four evil creatures of the world". In Chinese classical texts such as the "Classic of Mountains and Seas", the fiend is named alongside the Hundun (混沌), Qiongqi (窮奇) and Taowu (梼杌). They are opposed by the Four Holy Creatures, the Azure Dragon, Vermilion Bird, White Tiger and Black Tortoise. The four fiends are also juxtaposed with the four benevolent animals which are Qilin (麒麟), Dragon (龍), Turtle (龜) and Fenghuang (鳳凰).

The Chinese zodiac is a classification scheme based on the lunar calendar that assigns an animal and its reputed attributes to each year in a repeating 12-year cycle. The 12-year cycle is an approximation to the 11.85-year orbital period of Jupiter. Originating from China, the zodiac and its variations remain popular in many East Asian and Southeast Asian countries, such as Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand.

Niulang is a Chinese deity who is identified as the star Altair in the constellation Aquila. He was a legendary figure and main character in the popular Chinese folk tale The Cowherd and the Weaver Girl. The earliest record of this myth is over 2600 years ago.

Nüba, also known as Ba (魃) and as Hanba (旱魃), is a Chinese drought deity. "Ba" is her proper name, with the nü being an added indication of being feminine and han meaning "drought".

Shujun is a Chinese god of farming and cultivation, also known as Yijun and Shangjun. Alternatively he is a legendary culture hero of ancient times, who was in the family tree of ancient Chinese emperors descended from the Yellow Emperor (Huangdi). According to the various sources, Shujun was the son of Di Jun or else Houji's son or nephew. Shujun is one of the individuals named in Chinese mythology as helping to found the practice of agriculture in China, along with Houji, Di Jun, Shennong, and others. Shujun is specially credited with inventing the use of a draft animal of the bovine family to pull a plow to turn the soil prior to planting.

The Kunlun or Kunlun Shan is a mountain or mountain range in Chinese mythology, an important symbol representing the axis mundi and divinity.

Agriculture is an important theme in Chinese mythology. There are many myths about the invention of agriculture that have been told or written about in China. Chinese mythology refers to those myths found in the historical geographic area of China. This includes myths in Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups. Many of the myths about agriculture involve its invention by such deities or cultural heroes such as Shennong, Houji, Houtu, and Shujun: of these Shennong is the most famous, according to Lihui Yang (2005:70). There are also many other myths. Myths related to agriculture include how humans learned the use of fire, cooking, animal husbandry and the use of draft animals, inventions of various agricultural tools and implements, the domestication of various species of plants such as ginger and radishes, the evaluation and uses of various types of soil, irrigation by digging wells, and the invention of farmers markets. Other myths include events which made agriculture possible by destroying an excessive number of suns in the sky or ending the Great Flood.

Dogs are an important motif in Chinese mythology. These motifs include a particular dog which accompanies a hero, the dog as one of the twelve totem creatures for which years are named, a dog giving first provision of grain which allowed current agriculture, and claims of having a magical dog as an original ancestor in the case of certain ethnic groups.

Youdu in Chinese mythology is the capital of Hell, or Diyu. Among the various other geographic features believed of Diyu, the capital city has been thought to be named Youdu. It is generally conceived as being similar to a typical Chinese capital city, such as Chang'an, but surrounded with and pervaded with darkness.

Horses are an important motif in Chinese mythology. There are many myths about horses or horse-like beings, including the pony. Chinese mythology refers to those myths found in the historical geographic area of China. This includes myths in Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups. There are various motifs of horses in Chinese mythology. In some cases the focus is on a horse or horses as the protagonist of the action, in other cases they appear in a supporting role, sometimes as the locomotive power propelling a chariot and its occupant(s). According to a cyclical Chinese calendar system, the time period of 31 January 2014 - 18 February 2015 falls under the category of the (yang) Wood Horse.

Bovidae in Chinese mythology include various myths and legends about a group of biologically-distinct animals which form important motifs within Chinese mythology. There are many myths about the animals modernly classified as Bovidae, referring to oxen, sheep, goats, and mythological types such as "unicorns". Chinese mythology refers to those myths found in the historical geographic area of China, a geographic area which has evolved or changed somewhat through history. Thus this includes myths in Chinese and other languages, as transmitted by Han Chinese as well as other ethnic groups. There are various motifs of animals of the Bovidae biological family in Chinese mythology. These have often served as allusions in poetry and other literature. Some species are also used in the traditional Chinese calendar and time-keeping system.

Chinese mythological geography refers to the related mythological concepts of geography and cosmology, in the context of the geographic area now known as "China", which was typically conceived of as the center of the universe. The "Middle Kingdom" thus served as a reference point for a geography sometimes real and sometimes mythological, including lands and seas surrounding the Middle Land, with mountain peaks and sky above, with sacred grottoes and an underworld below, and even sometimes with some very abstract other worlds. Chinese mythological geography is very important because it involves a lot of mythology, history, and social science concepts of current usage as well as during previous uncounted millennia.

Legendary weapons, arms, and armor are important motifs in Chinese mythology as well as Chinese legend, cultural symbology, and fiction. Weapons featured in Chinese mythology, legend, cultural symbology, and fiction include Guanyu's pole weapon. This non-factually documented weapon has been known as the Green Dragon Crescent Blade. Other weapons from Chinese mythology, legend, cultural symbology, and fiction include the shield and battleax of the defiant dancer Xingtian, Yi's bow and arrows, given him by Di Jun, and the many weapons and armor of Chiyou, who is associated with the elemental power of metal. Chinese mythology, legend, cultural symbology, and fiction features the use of elemental weapons such as ones evoking the powers of wind and rain to influence battle.