An allele, or allelomorph, is a variant of the sequence of nucleotides at a particular location, or locus, on a DNA molecule.

In genetics, dominance is the phenomenon of one variant (allele) of a gene on a chromosome masking or overriding the effect of a different variant of the same gene on the other copy of the chromosome. The first variant is termed dominant and the second is called recessive. This state of having two different variants of the same gene on each chromosome is originally caused by a mutation in one of the genes, either new or inherited. The terms autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive are used to describe gene variants on non-sex chromosomes (autosomes) and their associated traits, while those on sex chromosomes (allosomes) are termed X-linked dominant, X-linked recessive or Y-linked; these have an inheritance and presentation pattern that depends on the sex of both the parent and the child. Since there is only one copy of the Y chromosome, Y-linked traits cannot be dominant or recessive. Additionally, there are other forms of dominance, such as incomplete dominance, in which a gene variant has a partial effect compared to when it is present on both chromosomes, and co-dominance, in which different variants on each chromosome both show their associated traits.

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and among populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as adaptation, speciation, and population structure.

A genetic screen or mutagenesis screen is an experimental technique used to identify and select individuals who possess a phenotype of interest in a mutagenized population. Hence a genetic screen is a type of phenotypic screen. Genetic screens can provide important information on gene function as well as the molecular events that underlie a biological process or pathway. While genome projects have identified an extensive inventory of genes in many different organisms, genetic screens can provide valuable insight as to how those genes function.

Human variability, or human variation, is the range of possible values for any characteristic, physical or mental, of human beings.

Ecological genetics is the study of genetics in natural populations. It combines ecology, evolution, and genetics to understand the processes behind adaptation. It is virtually synonymous with the field of molecular ecology.

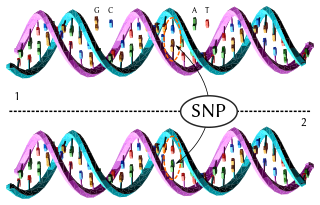

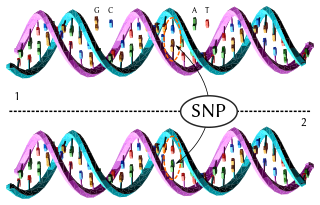

In genetics and bioinformatics, a single-nucleotide polymorphism is a germline substitution of a single nucleotide at a specific position in the genome. Although certain definitions require the substitution to be present in a sufficiently large fraction of the population, many publications do not apply such a frequency threshold.

Brassica oleracea is a plant species from the family Brassicaceae that includes many common cultivars used as vegetables, such as cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, collard greens, Savoy cabbage, kohlrabi, and gai lan. It was most likely first brought into cultivation in the Eastern Mediterranean region. The uncultivated form of the species, wild cabbage, originates from feral populations.

Supertasters are individuals whose sense of taste for certain flavors and foods, such as chocolate, is far more sensitive than the average person. The term originated with experimental psychologist Linda Bartoshuk and is not the result of response bias or a scaling artifact but appears to have an anatomical or biological basis.

Genetic association is when one or more genotypes within a population co-occur with a phenotypic trait more often than would be expected by chance occurrence.

TAS2R16 is a bitter taste receptor and one of the 25 TAS2Rs. TAS2Rs are receptors that belong to the G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) family. These receptors detect various bitter substances found in nature as agonists, and get stimulated. TAS2R16 receptor is mainly expressed within taste buds present on the surface of the tongue and palate epithelium. TAS2R16 is activated by bitter β-glucopyranosides

Cruciferous vegetables are vegetables of the family Brassicaceae with many genera, species, and cultivars being raised for food production such as cauliflower, cabbage, kale, garden cress, bok choy, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, mustard plant and similar green leaf vegetables. The family takes its alternative name from the shape of their flowers, whose four petals resemble a cross.

The Kell antigen system is a human blood group system, that is, a group of antigens on the human red blood cell surface which are important determinants of blood type and are targets for autoimmune or alloimmune diseases which destroy red blood cells. The Kell antigens are K, k, Kpa, Kpb, Jsa and Jsb. The Kell antigens are peptides found within the Kell protein, a 93-kilodalton transmembrane zinc-dependent endopeptidase which is responsible for cleaving endothelin-3.

Taste receptor 2 member 38 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TAS2R38 gene. TAS2R38 is a bitter taste receptor; varying genotypes of TAS2R38 influence the ability to taste both 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) and phenylthiocarbamide (PTC). Though it has often been proposed that varying taste receptor genotypes could influence tasting ability, TAS2R38 is one of the few taste receptors shown to have this function.

Laurence Hasbrouck Snyder was a pioneer in human genetics and president of the University of Hawaii.

The evolution of bitter taste receptors has been one of the most dynamic evolutionary adaptations to arise in multiple species. This phenomenon has been widely studied in the field of evolutionary biology because of its role in the identification of toxins often found on the leaves of inedible plants. A palate more sensitive to these bitter tastes would, theoretically, have an advantage over members of the population less sensitive to these poisonous substances because they would be much less likely to ingest toxic plants. Bitter-taste genes have been found in a host of vertebrates, including sharks and rays, and the same genes have been well characterized in several common laboratory animals such as primates and mice, as well as in humans. The primary gene responsible for encoding this ability in humans is the TAS2R gene family which contains 25 functional loci as well as 11 pseudogenes. The development of this gene has been well characterized, with proof that the ability evolved before the human migration out of Africa. The gene continues to evolve in the present day.

A taster is a person, by means of a human genotype, who is able to taste phenylthiocarbamide (PTC) and its derivative 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP). PTC tastes bitter to many people (tasters) but is tasteless to others (non-tasters).

PTC tasting is a classic genetic marker in human population genetics investigations.

Dennis T. Drayna is an American human geneticist known for his contributions to stuttering, human haemochromatosis, pitch, and taste. He is currently the Section Chief of Genetics of Communication Disorders at the U.S. National Institute for Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.

Sarah Anne Tishkoff is an American geneticist and the David and Lyn Silfen Professor in the Department of Genetics and Biology at the University of Pennsylvania. She also serves as a director for the American Society of Human Genetics and is an associate editor at PLOS Genetics, G3, and Genome Research. She is also a member of the scientific advisory board at the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.