Chicano or Chicana is a chosen identity for many Mexican Americans in the United States. The label Chicano is sometimes used interchangeably with Mexican American, although the terms have different meanings. While Mexican American identity emerged to encourage assimilation into White American society and separate the community from African-American political struggle, Chicano identity emerged among anti-assimilationist youth, some of whom belonged to the Pachuco subculture, who reclaimed the term. Chicano was widely reclaimed in the 1960s and 1970s to express political empowerment, ethnic solidarity, and pride in being of Indigenous descent, diverging from the more assimilationist Mexican American identity. Chicano Movement leaders were influenced by and collaborated with Black Power leaders and activists. Chicano youth in barrios rejected cultural assimilation into whiteness and embraced their identity and worldview as a form of empowerment and resistance.

M.E.Ch.A. is a US-based organization that seeks to promote Chicano unity and empowerment through political action. The acronym of the organization's name is the Chicano word mecha, which is the Chicano pronunciation of the English word match and therefore symbolic of a fire or spark; mecha in Spanish means fuse or wick. The motto of MEChA is 'La Union Hace La Fuerza'.

The Plan Espiritual de Aztlán was a pro-indigenist manifesto advocating Chicano nationalism and self-determination for Mexican Americans. It was adopted by the First National Chicano Liberation Youth Conference, a March 1969 convention hosted by Rodolfo Gonzales's Crusade for Justice in Denver, Colorado.

Latino studies is an academic discipline which studies the experience of people of Latin American ancestry in the United States. Closely related to other ethnic studies disciplines such as African-American studies, Asian American studies, and Native American studies, Latino studies critically examines the history, culture, politics, issues, sociology, spirituality (Indigenous) and experiences of Latino people. Drawing from numerous disciplines such as sociology, history, literature, political science, religious studies and gender studies, Latino studies scholars consider a variety of perspectives and employ diverse analytical tools in their work.

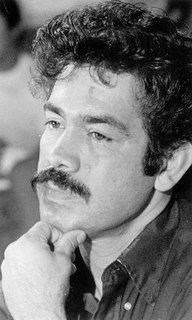

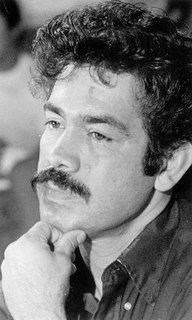

Rodolfo "Corky" Gonzales was a Chicano boxer, poet, political organizer, and activist. Gonzales was one of many leaders for the Crusade for Justice in Denver, Colorado. The Crusade for Justice was noted for being an urban rights and Chicano cultural urban movement during the 1960s focusing on social, political and economic justice for Chicanos. Gonzales convened the first-ever Chicano Youth Liberation Conference in 1968, which was poorly attended due to timing and weather conditions. Gonzales tried again in March 1969, and established what is commonly known as the First Chicano Youth Liberation Conference. This Conference was attended by many future Chicano activists and artists. The conference also birthed the Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, a pro-indigenist manifesto advocating revolutionary Chicano nationalism and self-determination for all Chicanos. Through the Crusade for Justice, Gonzales organized the Mexican American people of Denver to fight for their cultural, political, and economic rights, leaving his mark on Chicano History.

Chicanismo is the ideology behind the Chicano movement. It is an ideology based on a number of important factors that helped shape a social uprising in order to fight for the liberties of Mexican-Americans. Chicanismo was shaped by a number of intellectuals and influential activists as well as by the artistic and political sphere, and the many contributors to the ideology collaborated to create a strong sense of self-identity within the Chicano community. Cultural affirmation became one of the main methods of developing Chicanismo. This cultural affirmation was achieved by bringing a new sense of nationalism for Mexican-Americans, drawing ties to the long-forgotten history of Chicanos in lands that were very recently Mexican, and creating a symbolic connection to the ancestral ties of Mesoamerica and the Nahuatl language.

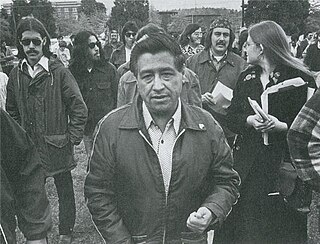

The Chicano Movement, also referred to as El Movimiento, was a social and political movement inspired by prior acts of resistance among people of Mexican descent, especially of Pachucos in the 1940s and 1950s, and the Black Power movement, that worked to embrace a Chicano/a identity and worldview that combated structural racism, encouraged cultural revitalization, and achieved community empowerment by rejecting assimilation. Prior to the Movement, Chicano/a was a classist term of derision, reclaimed only by some Pachucos who adopted it as an expression of defiance to Anglo-American society. As a result of the Movement, Chicanismo arose and Chicano/a was widely reclaimed in the 1960s and 1970s to express political autonomy, ethnic and cultural solidarity, and pride in being of Indigenous descent, diverging from the assimilationist Mexican-American identity.

Alberto Baltazar Urista Heredia better known by his nom de plume Alurista, is a Chicano poet and activist.

Chicano nationalism is the pro-indigenist ethnic nationalist ideology of Chicanos. While there were nationalistic aspects of the Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, the movement tended to emphasize civil rights and political and social inclusion rather than nationalism. For this reason, Chicano nationalism is better described as an ideology than as a political movement.

Chicana/o studies, also known as Chican@ studies, originates from the Chicano Movement of the late 1960s and 1970s, and is the study of the Chicana/o and Latina/o experience. Chican@ studies draws upon a variety of fields, including history, sociology, the arts, and Chican@ literature. The area of studies additionally emphasizes the importance of Chican@ educational materials taught by Chican@ educators for Chican@ students.

Las Adelitas de Aztlán was a short-lived Mexican American female civil rights organization that was created by Gloria Arellanes and Gracie and Hilda Reyes in 1970. Gloria Arellanes and Gracie and Hilda Reyes were all former members of the Brown Berets, another Mexican American Civil rights organization that had operated concurrently during the 1960s and 1970s in the California area. The founders left the Brown Berets due to enlarging gender discrepancies and disagreements that caused much alienation amongst their female members. The Las Adelitas De Aztlan advocated for Mexican-American Civil rights, better conditions for workers, protested police brutality and advocated for women's rights for the Latino community. The name of the organization was a tribute to Mexican female soldiers or soldaderas that fought during the Mexican Revolution of the early twentieth century.

Juan Gómez-Quiñones was an American historian, professor of history, poet, and activist. He was best known for his work in the field of Chicana/o history. As a co-editor of the Plan de Santa Bárbara, an educational manifesto for the implementation of Chicano studies programs in universities nationwide, he was an influential figure in the development of the field.

Anna Nieto-Gomez was a central part of the early Chicana movement and founded the feminist journal, Encuentro Femenil, in which she and other Chicana writers addressed issues affecting the Latina community, such as childcare, reproductive rights, and the feminization of poverty.

Hijas de Cuauhtémoc was a student Chicana feminist newspaper founded in 1971 by Anna Nieto-Gómez and Adelaida Castillo while both were students at California State University, Long Beach.

Patricia Zavella is an anthropologist and professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz in the Latin American and Latino Studies department. She has spent a career advancing Latina and Chicana feminism through her scholarship, teaching, and activism. She was president of the Association of Latina and Latino Anthropologists and has served on the executive board of the American Anthropological Association. In 2016, Zavella received the American Anthropological Association's award from the Committee on Gender Equity in Anthropology to recognize her career studying gender discrimination. The awards committee said Zavella’s career accomplishments advancing the status of women, and especially Latina and Chicana women have been exceptional. She has made critical contributions to understanding how gender, race, nation, and class intersect in specific contexts through her scholarship, teaching, advocacy, and mentorship. Zavella’s research focuses on migration, gender and health in Latina/o communities, Latino families in transition, feminist studies, and ethnographic research methods. She has worked on many collaborative projects, including an ongoing partnership with Xóchitl Castañeda where she wrote four articles some were in English and others in Spanish. The Society for the Anthropology of North America awarded Zavella the Distinguished Career Achievement in the Critical Study of North America Award in the year 2010. She has published many books including, most recently, "I'm Neither Here Nor There, Mexicans"Quotidian Struggles with Migration and Poverty, which focuses on working class Mexican Americans struggle for agency and identity in Santa Cruz County.

The term Chicanafuturism was originated by scholar Catherine S. Ramírez which she introduced in Aztlán: A Journal of Chicano Studies in 2004. The term is a portmanteau of 'chicana' and 'futurism', inspired by the developing movement of Afrofuturism. The word 'chicana' refers to a woman or girl of Mexican origin or descent. However, 'Chicana' itself serves as a chosen identity for many female Mexican Americans in the United States, to express self-determination and solidarity in a shared cultural, ethnic, and communal identity while openly rejecting assimilation. Ramírez created the concept of Chicanafuturism as a response to white androcentrism that she felt permeated science-fiction and American society. Chicanafuturism can be understood as part of a larger genre of Latino futurisms.

A Mexican American is a resident of the United States who is of Mexican descent. Mexican American-related topics include the following:

This is an alphabetical index of topics related to Hispanic and Latino Americans.

Maria Luisa Alanis Ruiz is a Chicana activist and academic in Oregon. She was born in Linares, Mexico and immigrated to the United States. She has been active in Chicano and Latino social justice work in the state of Oregon since the 1970s, helped found Portland's Cinco de Mayo festival, and has been a long-term volunteer for the Portland-Guadalajara Sister-City Association. Much of her academic career was spent developing Chicano and Latino Studies programming and curricula for Portland State University.