The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 190 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of last resort to national governments, and a leading supporter of exchange-rate stability. Its stated mission is "working to foster global monetary cooperation, secure financial stability, facilitate international trade, promote high employment and sustainable economic growth, and reduce poverty around the world." Established on December 27, 1945 at the Bretton Woods Conference, primarily according to the ideas of Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, it started with 29 member countries and the goal of reconstructing the international monetary system after World War II. It now plays a central role in the management of balance of payments difficulties and international financial crises. Through a quota system, countries contribute funds to a pool from which countries can borrow if they experience balance of payments problems. As of 2016, the fund had SDR 477 billion.

In finance, a haircut is the difference between the current market value of an asset and the value ascribed to that asset for purposes of calculating regulatory capital or loan collateral. The amount of the haircut reflects the perceived risk of the asset falling in value in an immediate cash sale or liquidation. The larger the risk or volatility of the asset price, the larger the haircut.

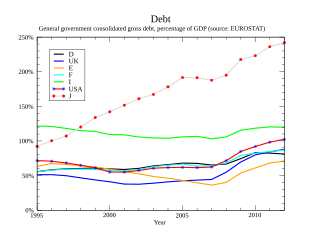

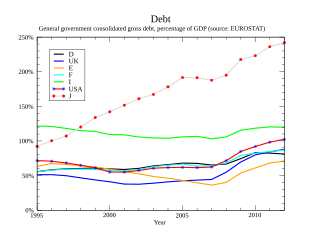

A country's gross government debt is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occurs when a government's expenditures exceed revenues. Government debt may be owed to domestic residents, as well as to foreign residents. If owed to foreign residents, that quantity is included in the country's external debt.

Brady bonds are dollar-denominated bonds, issued mostly by Latin American countries in the late 1980s. The bonds were named after U.S. Treasury Secretary Nicholas Brady, who proposed a novel debt-reduction agreement for developing countries.

A sovereign default is the failure or refusal of the government of a sovereign state to pay back its debt in full when due. Cessation of due payments may either be accompanied by that government's formal declaration that it will not pay its debts (repudiation), or it may be unannounced. A credit rating agency will take into account in its gradings capital, interest, extraneous and procedural defaults, and failures to abide by the terms of bonds or other debt instruments.

The European debt crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis or the European sovereign debt crisis, was a multi-year debt crisis that took place in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until the mid to late 2010s. Several eurozone member states were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or to bail out over-indebted banks under their national supervision without the assistance of third parties like other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Greece faced a sovereign debt crisis in the aftermath of the financial crisis of 2007–2008. Widely known in the country as The Crisis, it reached the populace as a series of sudden reforms and austerity measures that led to impoverishment and loss of income and property, as well as a small-scale humanitarian crisis. In all, the Greek economy suffered the longest recession of any advanced mixed economy to date. As a result, the Greek political system has been upended, social exclusion increased, and hundreds of thousands of well-educated Greeks have left the country.

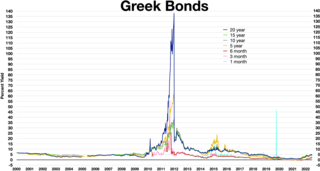

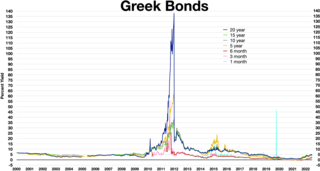

From late 2009, fears of a sovereign debt crisis in some European states developed, with the situation becoming particularly tense in early 2010. Greece was most acutely affected, but fellow Eurozone members Cyprus, Ireland, Italy, Portugal, and Spain were also significantly affected. In the EU, especially in countries where sovereign debt has increased sharply due to bank bailouts, a crisis of confidence has emerged with the widening of bond yield spreads and risk insurance on credit default swaps between these countries and other EU members, most importantly Germany.

The European Stability Mechanism (ESM) is an intergovernmental organization located in Luxembourg City, which operates under public international law for all eurozone member states having ratified a special ESM intergovernmental treaty. It was established on 27 September 2012 as a permanent firewall for the eurozone, to safeguard and provide instant access to financial assistance programmes for member states of the eurozone in financial difficulty, with a maximum lending capacity of €500 billion. It has replaced two earlier temporary EU funding programmes: the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) and the European Financial Stabilisation Mechanism (EFSM).

International lender of last resort (ILLR) is a facility prepared to act when no other lender is capable or willing to lend in sufficient volume to provide or guarantee liquidity in order to avert a sovereign debt crisis or a systemic crisis. No effective international lender of last resort currently exists.

Debt crisis is a situation in which a government loses the ability of paying back its governmental debt. When the expenditures of a government are more than its tax revenues for a prolonged period, the government may enter into a debt crisis. Various forms of governments finance their expenditures primarily by raising money through taxation. When tax revenues are insufficient, the government can make up the difference by issuing debt.

The 2012–2013 Cypriot financial crisis was an economic crisis in the Republic of Cyprus that involved the exposure of Cypriot banks to overleveraged local property companies, the Greek government-debt crisis, the downgrading of the Cypriot government's bond credit rating to junk status by international credit rating agencies, the consequential inability to refund its state expenses from the international markets and the reluctance of the government to restructure the troubled Cypriot financial sector.

The eurozone crisis is an ongoing financial crisis that has made it difficult or impossible for some countries in the euro area to repay or re-finance their government debt without the assistance of third parties.

The Second Economic Adjustment Programme for Greece, usually referred to as the second bailout package or the second memorandum, is a memorandum of understanding on financial assistance to the Hellenic Republic in order to cope with the Greek government-debt crisis.

This article details the fourteen austerity packages passed by the Government of Greece between 2010 and 2017. These austerity measures were a result of the Greek government-debt crisis and other economic factors. All of the legislation listed remains in force.

The Economic Adjustment Programme for Cyprus, usually referred to as the Bailout programme, is a memorandum of understanding on financial assistance to the Republic of Cyprus in order to cope with the 2012–13 Cypriot financial crisis.

Greylock Capital Management, LLC is a U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission registered alternative investment adviser that invests globally in high yield, undervalued, and distressed assets worldwide, particularly in emerging and frontier markets. The firm was founded in 2004 by Hans Humes from a portfolio of emerging market assets managed by Humes while at Van Eck Global. AJ Mediratta joined the firm in 2008 from Bear Stearns and serves as its president.

Adam Lerrick is an American economist and government official currently serving as Counselor to the Secretary of the Treasury, having previously been President Donald Trump's nominee for Assistant Secretary of the Treasury for International Finance. Lerrick has served as an economist at the American Enterprise Institute.

In 2009–2010, due to substantial public and private sector debt, and "the intimate sovereign-bank linkages" the eurozone crisis impacted periphery countries. This resulted in significant financial sector instability in Europe; banks' solvency risks grew, which had direct implications for their funding liquidity. The European central bank (ECB), as the monetary union's central bank, responded to the sovereign debt crisis with a series of conventional and unconventional measures, including a decrease in the key policy interest rate, and three-year long-term refinancing operation (LTRO) liquidity injections in December 2011 and February 2012, and the announcement of the outright monetary transactions (OMT) program in the summer of 2012. The ECB acted as a de facto lender-of-last-resort (LOLR) to the euro area banking system, providing banks with cash flow in exchange for collateral, as well as a buyer of last resort (BOLR), purchasing eurozone sovereign bonds. However, the ECB's policies have been criticised for their economic repercussions as well as its political agenda.