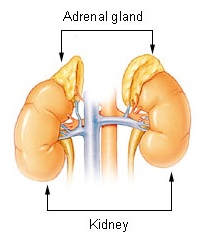

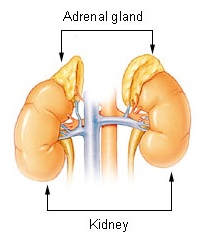

Waterhouse–Friderichsen syndrome (WFS) is defined as adrenal gland failure due to bleeding into the adrenal glands, commonly caused by severe bacterial infection. Typically, it is caused by Neisseria meningitidis.

Coagulation, also known as clotting, is the process by which blood changes from a liquid to a gel, forming a blood clot. It results in hemostasis, the cessation of blood loss from a damaged vessel, followed by repair. The process of coagulation involves activation, adhesion and aggregation of platelets, as well as deposition and maturation of fibrin.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) is a condition in which blood clots form throughout the body, blocking small blood vessels. Symptoms may include chest pain, shortness of breath, leg pain, problems speaking, or problems moving parts of the body. As clotting factors and platelets are used up, bleeding may occur. This may include blood in the urine, blood in the stool, or bleeding into the skin. Complications may include organ failure.

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) is a blood disorder that results in blood clots forming in small blood vessels throughout the body. This results in a low platelet count, low red blood cells due to their breakdown, and often kidney, heart, and brain dysfunction. Symptoms may include large bruises, fever, weakness, shortness of breath, confusion, and headache. Repeated episodes may occur.

The partial thromboplastin time (PTT), also known as the activated partial thromboplastin time, is a blood test that characterizes coagulation of the blood. A historical name for this measure is the kaolin-cephalin clotting time (KCCT), reflecting kaolin and cephalin as materials historically used in the test. Apart from detecting abnormalities in blood clotting, partial thromboplastin time is also used to monitor the treatment effect of heparin, a widely prescribed drug that reduces blood's tendency to clot.

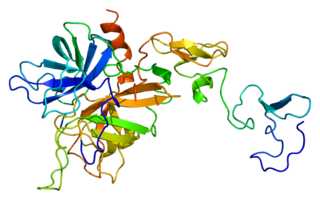

Protein S deficiency is a disorder associated with increased risk of venous thrombosis. Protein S, a vitamin K-dependent physiological anticoagulant, acts as a nonenzymatic cofactor to activate protein C in the degradation of factor Va and factor VIIIa.

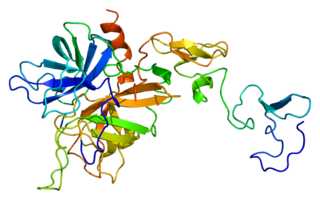

Protein C, also known as autoprothrombin IIA and blood coagulation factor XIV, is a zymogen, that is, an inactive enzyme. The activated form plays an important role in regulating anticoagulation, inflammation, and cell death and maintaining the permeability of blood vessel walls in humans and other animals. Activated protein C (APC) performs these operations primarily by proteolytically inactivating proteins Factor Va and Factor VIIIa. APC is classified as a serine protease since it contains a residue of serine in its active site. In humans, protein C is encoded by the PROC gene, which is found on chromosome 2.

Thrombophilia is an abnormality of blood coagulation that increases the risk of thrombosis. Such abnormalities can be identified in 50% of people who have an episode of thrombosis that was not provoked by other causes. A significant proportion of the population has a detectable thrombophilic abnormality, but most of these develop thrombosis only in the presence of an additional risk factor.

A schistocyte or schizocyte is a fragmented part of a red blood cell. Schistocytes are typically irregularly shaped, jagged, and have two pointed ends.

Fresh frozen plasma (FFP) is a blood product made from the liquid portion of whole blood. It is used to treat conditions in which there are low blood clotting factors or low levels of other blood proteins. It may also be used as the replacement fluid in plasma exchange. Using ABO compatible plasma, while not required, may be recommended. Use as a volume expander is not recommended. It is administered by slow injection into a vein.

Hypoprothrombinemia is a rare blood disorder in which a deficiency in immunoreactive prothrombin, produced in the liver, results in an impaired blood clotting reaction, leading to an increased physiological risk for spontaneous bleeding. This condition can be observed in the gastrointestinal system, cranial vault, and superficial integumentary system, affecting both the male and female population. Prothrombin is a critical protein that is involved in the process of hemostasis, as well as illustrating procoagulant activities. This condition is characterized as an autosomal recessive inheritance congenital coagulation disorder affecting 1 per 2,000,000 of the population, worldwide, but is also attributed as acquired.

Warfarin-induced skin necrosis is a condition in which skin and subcutaneous tissue necrosis occurs due to acquired protein C deficiency following treatment with anti-vitamin K anticoagulants.

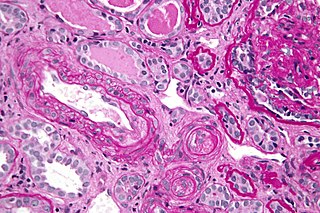

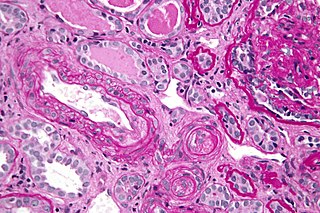

Thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA) is a pathology that results in thrombosis in capillaries and arterioles, due to an endothelial injury. It may be seen in association with thrombocytopenia, anemia, purpura and kidney failure.

Protein C deficiency is a rare genetic trait that predisposes to thrombotic disease. It was first described in 1981. The disease belongs to a group of genetic disorders known as thrombophilias. Protein C deficiency is associated with an increased incidence of venous thromboembolism, whereas no association with arterial thrombotic disease has been found.

Kasabach–Merritt syndrome (KMS), also known as hemangioma with thrombocytopenia, is a rare disease, usually of infants, in which a vascular tumor leads to decreased platelet counts and sometimes other bleeding problems, which can be life-threatening. It is also known as hemangioma thrombocytopenia syndrome. It is named after Haig Haigouni Kasabach and Katharine Krom Merritt, the two pediatricians who first described the condition in 1940.

Calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA) or “Grey Scale”, is a rare syndrome characterized by painful skin lesions. The pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is unclear but believed to involve calcification of the small blood vessels located within the fatty tissue and deeper layers of the skin, blood clots, and eventual death of skin cells due to lack of blood flow. It is seen mostly in people with end-stage kidney disease but can occur in the earlier stages of chronic kidney disease and rarely in people with normally functioning kidneys. Calciphylaxis is a rare but serious disease, believed to affect 1-4% of all dialysis patients. It results in chronic non-healing wounds and indicates poor prognosis, with typical life expectancy of less than one year.

Capnocytophaga canimorsus is a fastidious, slow-growing, Gram-negative rod of the genus Capnocytophaga. It is a commensal bacterium in the normal gingival microbiota of canine and feline species, but can cause illness in humans. Transmission may occur through bites, licks, or even close proximity with animals. C. canimorsus generally has low virulence in healthy individuals, but has been observed to cause severe, even grave, illness in persons with pre-existing conditions. The pathogenesis of C. canimorsus is still largely unknown, but increased clinical diagnoses have fostered an interest in the bacillus. Treatment with antibiotics is effective in most cases, but the most important yet basic diagnostic tool available to clinicians remains the knowledge of recent exposure to canines or felines.

Cryofibrinogenemia refers to a condition classified as a fibrinogen disorder in which a person's blood plasma is allowed to cool substantially, causing the (reversible) precipitation of a complex containing fibrinogen, fibrin, fibronectin, and, occasionally, small amounts of fibrin split products, albumin, immunoglobulins and other plasma proteins.

Upshaw–Schulman syndrome (USS) is the recessively inherited form of thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), a rare and complex blood coagulation disease. USS is caused by the absence of the ADAMTS13 protease resulting in the persistence of ultra large von Willebrand factor multimers (ULVWF), causing episodes of acute thrombotic microangiopathy with disseminated multiple small vessel obstructions. These obstructions deprive downstream tissues from blood and oxygen, which can result in tissue damage and death. The presentation of an acute USS episode is variable but usually associated with thrombocytopenia, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) with schistocytes on the peripheral blood smear, fever and signs of ischemic organ damage in the brain, kidney and heart.

Retiform purpura is the result of total vascular blockage and damage to the skin's blood vessels. The skin then shows lesions, appearing due to intravascular issues where clots, proteins, or emboli block skin vessels. They can also result from direct harm to the vessel walls, as seen in conditions like vasculitis, calciphylaxis, and certain severe opportunistic infections.