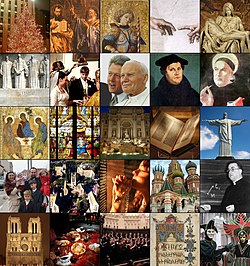

| Part of a series on |

| Christian culture |

|---|

|

| Christianity portal |

The Religious Society of Friends, commonly known as Quakers, encouraged some values which may have been conducive to encouraging scientific talents. A theory suggested by David Hackett Fischer in his book Albion's Seed indicated early Quakers in the US preferred "practical study" to the more traditional studies of Greek or Latin popular with the elite. Another theory suggests their avoidance of dogma or clergy gave them a greater flexibility in response to science.

Contents

Despite those arguments a major factor is agreed to be that the Quakers were initially discouraged or forbidden to go to the major law or humanities schools in Britain due to the Test Act. They also at times faced similar discriminations in the United States, as many of the colonial universities had a Puritan or Anglican orientation. This led them to attend "Godless" institutions or forced them to rely on hands-on scientific experimentation rather than academia.

Because of these issues it has been stated that Quakers are better represented in science than most religions. Some sources, including Pendlehill ( Thomas 2000 ) and Encyclopædia Britannica, indicate that for over two centuries they were overrepresented in the Royal Society. Mention is made of this possibility in studies referenced in religiosity and intelligence and in a book by Arthur Raistrick. Regardless of whether this is still accurate, there have been several noteworthy members of this denomination in science.

Other notable scientists had Quaker backgrounds without being practicing Quakers themselves. These include John Bardeen, whose mother was a Quaker, [1] and Karl Barry Sharpless, who attended a Quaker school and stated that Quaker values contributed to his success as a chemist. [2] Together with Frederick Sanger (listed below), this means that three of the four individuals who as of 2023 have won two Nobel Prizes in science categories were raised by Quakers.