The 22nd century BC are the years between 2200 and 2101 years before the birth of Jesus Christ.

Sumer is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia, emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. Like nearby Elam, it is one of the cradles of civilization, along with Egypt, the Indus Valley, the Erligang culture of the Yellow River valley, Caral-Supe, and Mesoamerica. Living along the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, Sumerian farmers grew an abundance of grain and other crops, a surplus which enabled them to form urban settlements. The world's earliest known texts come from the Sumerian cities of Uruk and Jemdet Nasr, and date to between c. 3350 – c. 2500 BC, following a period of proto-writing c. 4000 – c. 2500 BC.

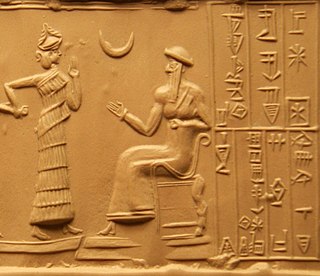

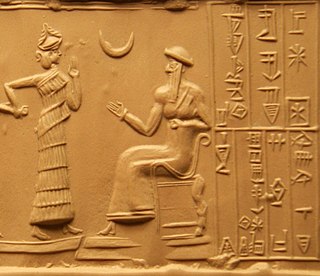

The Sumerian King List or Chronicle of the One Monarchy is an ancient literary composition written in Sumerian that was likely created and redacted to legitimize the claims to power of various city-states and kingdoms in southern Mesopotamia during the late third and early second millennium BC. It does so by repetitively listing Sumerian cities, the kings that ruled there, and the lengths of their reigns. Especially in the early part of the list, these reigns often span thousands of years. In the oldest known version, dated to the Ur III period but probably based on Akkadian source material, the SKL reflected a more linear transition of power from Kish, the first city to receive kingship, to Akkad. In later versions from the Old Babylonian period, the list consisted of a large number of cities between which kingship was transferred, reflecting a more cyclical view of how kingship came to a city, only to be inevitably replaced by the next. In its best-known and best-preserved version, as recorded on the Weld-Blundell Prism, the SKL begins with a number of antediluvian kings, who ruled before a flood swept over the land, after which kingship went to Kish. It ends with a dynasty from Isin, which is well-known from other contemporary sources.

The history of Sumer spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE in southern Mesopotamia, and is taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumer was the region's earliest known civilization and ended with the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE. It was followed by a transitional period of Amorite states before the rise of Babylonia in the 18th century BCE.

Lagash was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Al-Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East. The ancient site of Nina is around 10 km (6.2 mi) away and marks the southern limit of the state. Nearby Girsu, about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state. The Lagash state's main temple was the E-ninnu at Girsu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. The Lagash state incorporated the ancient cities of Lagash, Girsu, Nina.

Ur-Nammu founded the Sumerian Third Dynasty of Ur, in southern Mesopotamia, following several centuries of Akkadian and Gutian rule. His main achievement was state-building, and Ur-Nammu is chiefly remembered today for his legal code, the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest known surviving example in the world. He held the titles of "King of Ur, and King of Sumer and Akkad".

Samsu-iluna was the seventh king of the founding Amorite dynasty of Babylon, ruling from 1749 BC to 1712 BC, or from 1686 to 1648 BC. He was the son and successor of Hammurabi by an unknown mother. His reign was marked by the violent uprisings of areas conquered by his father and the abandonment of several important cities.

The Third Dynasty of Ur, also called the Neo-Sumerian Empire, refers to a 22nd to 21st century BC Sumerian ruling dynasty based in the city of Ur and a short-lived territorial-political state which some historians consider to have been a nascent empire.

Shulgi of Ur was the second king of the Third Dynasty of Ur. He reigned for 48 years, from c. 2094 – c. 2046 BC or possibly c. 2030 – 1982 BC. His accomplishments include the completion of construction of the Great Ziggurat of Ur, begun by his father Ur-Nammu. On his inscriptions, he took the titles "King of Ur", "King of Sumer and Akkad" and "King of the four corners of the universe". He used the symbol for divinity before his name, marking his apotheosis, from the 23rd year of his reign.

Lugal-Zage-Si of Umma was the last Sumerian king before the conquest of Sumer by Sargon of Akkad and the rise of the Akkadian Empire, and was considered as the only king of the third dynasty of Uruk, according to the Sumerian King List. Initially, as king of Umma, he led the final victory of Umma in the generation-long conflict with the city-state Lagash for the fertile plain of Gu-Edin. Following up on this success, he then united Sumer briefly as a single kingdom.

Bad-tibira, "Wall of the Copper Worker(s)", or "Fortress of the Smiths", identified as modern Tell al-Madineh, between Ash Shatrah and Tell as-Senkereh and 33 kilometers northeast of ancient Girsu in southern Iraq, was an ancient Sumerian city on the Iturungal canal, which appears among antediluvian cities in the Sumerian King List. Its Akkadian name was Dûr-gurgurri. It was also called Παντιβίβλος (Pantibiblos) by Greek authors such as Berossus, transmitted by Abydenus and Apollodorus. This may reflect another version of the city's name, Patibira, "Canal of the Smiths".

Enmebaragesi (Sumerian: 𒂗𒈨𒁈𒄄𒋛En-me-barag-gi-se [EN-ME-BARA2-GI4-SE]) originally Mebarasi (𒈨𒁈𒋛) was the penultimate king of the first dynasty of Kish and is recorded as having reigned 900 years in the Sumerian King List. Like his son and successor Aga he reigned during a period when Kish had hegemony over Sumer. Enmebaragesi signals a momentous documentary leap from mytho-history to history, since he is the earliest ruler on the king list whose name is attested directly from archaeology.

The history of Mesopotamia ranges from the earliest human occupation in the Paleolithic period up to Late antiquity. This history is pieced together from evidence retrieved from archaeological excavations and, after the introduction of writing in the late 4th millennium BC, an increasing amount of historical sources. While in the Paleolithic and early Neolithic periods only parts of Upper Mesopotamia were occupied, the southern alluvium was settled during the late Neolithic period. Mesopotamia has been home to many of the oldest major civilizations, entering history from the Early Bronze Age, for which reason it is often called a cradle of civilization.

The Awan Dynasty was the first dynasty of Elam of which very little of anything is known today, appearing at the dawn of historical record. The Dynasty corresponds to the early part of the Old Elamite period, it was succeeded by the Shimashki Dynasty and later the Sukkalmah Dynasty. The Elamites were likely major rivals of neighboring Sumer from remotest antiquity; they were said to have been defeated by Enmebaragesi of Kish, who is the earliest archaeologically attested Sumerian king, as well as by a later monarch, Eannatum I of Lagash.

The Dynasty of Isin refers to the final ruling dynasty listed on the Sumerian King List (SKL). The list of the Kings Isin with the length of their reigns, also appears on a cuneiform document listing the kings of Ur and Isin, the List of Reigns of Kings of Ur and Isin.

Gungunum was a king of the city state of Larsa in southern Mesopotamia, ruling from 1932 to 1906 BC. According to the traditional king list for Larsa, he was the fifth king to rule the city, and in his own inscriptions he identifies himself as a son of Samium and brother to his immediate predecessor Zabaya. His name is Amorite, and originates in the word gungun, meaning "protection", "defence" or "shelter".

The Guti, also known by the derived exonyms Gutians or Guteans, were a people of the ancient Near East. Their homeland was known as Gutium.

Kazalla or Kazallu (Ka-zal-luki) is the name given in Akkadian sources to a city in the ancient Near East whose locations is unknown. Its god is Numushda with his consort Namrat. There are indications that the god Lugal-awak also lived in Kazallu.

King of Sumer and Akkad was a royal title in Ancient Mesopotamia combining the titles of "King of Akkad", the ruling title held by the monarchs of the Akkadian Empire with the title of "King of Sumer". The title simultaneously laid a claim on the legacy and glory of the ancient empire that had been founded by Sargon of Akkad and expressed a claim to rule the entirety of lower Mesopotamia. Despite both of the titles "King of Sumer" and "King of Akkad" having been used by the Akkadian kings, the title was not introduced in its combined form until the reign of the Neo-Sumerian king Ur-Nammu, who created it in an effort to unify the southern and northern parts of lower Mesopotamia under his rule. The older Akkadian kings themselves might have been against linking Sumer and Akkad in such a way.

The Isin-Larsa period is a phase in the history of ancient Mesopotamia, which extends between the end of the Third Dynasty of Ur and the conquest of Mesopotamia by King Hammurabi of Babylon leading to the creation of the First Babylonian dynasty. According to the approximate conventional dating, this period begins in 2025 BCE and ended in 1763 BCE. It constitutes the first part of the Old Babylonian period, the second part being the period of domination of the first dynasty of Babylon, which ends with the Sack of Babylon in 1595 BCE and the rise of the Kassites.