The following outline is provides an overview of Sikhism, or Sikhi.

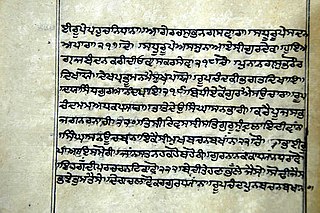

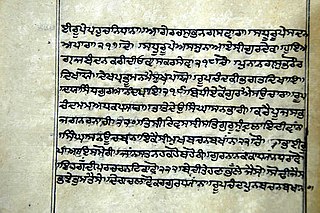

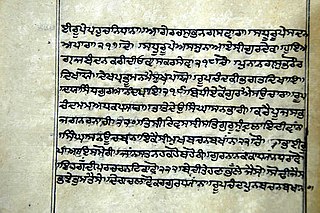

The principal Sikh scripture is the Adi Granth, more commonly called the Guru Granth Sahib. The second most important scripture of the Sikhs is the Dasam Granth. Both of these consist of text which was written or authorised by the Sikh Gurus.

The Janamsakhis, are popular hagiographies of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. Considered by scholars as semi-legendary biographies, they were based on a Sikh oral tradition of historical fact, homily, and legend, with the first janamsakhi were composed between 50 and 80 years after his death. Many more were written in the 17th and 18th century. The largest Guru Nanak Prakash, with about 9,700 verses, was written in the early 19th century by Kavi Santokh Singh.

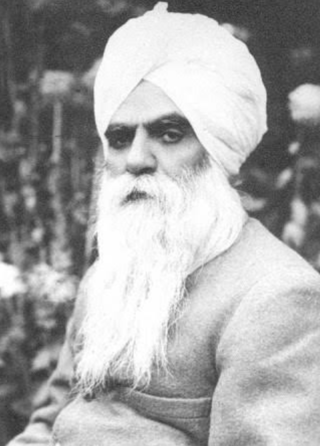

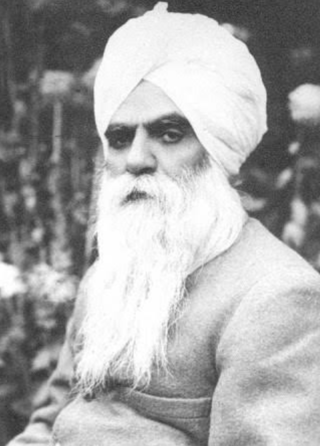

Vir Singh was an Indian poet, scholar and theologist of the Sikh revival movement, playing an important part in the renewal of Punjabi literary tradition. Singh's contributions were so important and influential that he became canonized as Bhai, an honorific often given to those who could be considered a saint of the Sikh faith.

Bhai Bala was a companion of Guru Nanak. Born in Talwandi into a Sandhu Jat family, Bala was also a close associate of Bhai Mardana.

Bhai Mardana was one of the first Sikhs and longtime companion of Guru Nanak Dev, first in the line of gurus noted in Sikhism. Bhai Mardana was a Muslim by-birth who would accompany Guru Nanak Dev on his journeys and became one of his first disciples and followers, and converted to the newly established religion. Bhai Mardana was born to a Mirasi Muslim family, a couple, Badra and Lakkho, of Rai Bhoi di Talwandi, now Nankana Sahib of Pakistan. He was the seventh born, all other children had died at birth. He had very good knowledge of music and played rabāb when Guru Nanak sung Gurbani. Swami Haridas was the disciple of Bhai Mardana and learnt Classical Music from him.

Nanakpanthi, also known as Nanakshahi, is a Sikh sect which follows Guru Nanak (1469-1539), the founder of Sikhism.

Varan Bhai Gurdas, also known as Varan Gyan Ratnavali, is the name given to the 40 vars which is traditionally attributed to Bhai Gurdas.

Suraj Prakash, also called Gurpartāp Sūraj Granth, is a popular and monumental hagiographic text about Sikh Gurus written by Kavi Santokh Singh (1787–1843) and published in 1843 CE. It consists of life legends performed by Sikh Gurus and historic Sikhs such as Baba Banda Bahadur in 51,820 verses. Most modern writing on the Sikh Gurus finds its basis from this text.

Bhat Vahis were scrolls or records maintained by Bhatts also known as Bhatra. The majority of Bhat Sikhs originate from Punjab and were amongst the first followers of Guru Nanak. Bhat tradition and Sikh text states their ancestors came from Punjab, where the Raja Shivnabh and his kingdom became the original 16th century followers of Guru Nanak, the founder of Sikhism. The Raja's grandson Prince Baba Changa earned the title ‘Bhat Rai’ – the ‘Raja of Poets, and then settled himself and his followers all over India as missionaries to spread the word of Guru Nanak, where many northern Indians became Bhat Sikhs. The majority were from the northern Brahmin caste ,(Bhat ) as the Prince Baba Changa shared the Brahmin heritage. The sangat also had many members from different areas of the Sikh caste spectrum, such as the Hindu Rajputs and Hindu Jats who joined due to Bhat Sikh missionary efforts. The Bhats also contributed 123 compositions in the Sri Guru Granth Sahib (pp.1389–1409), known as the "Bhata de Savaiyye". There hereditary occupations consisted of bards, poets, missionaries, astrologists, genealogists, salesmen.

Hikaaitaan or Hikāyatān is a title given to the semi-legendary set of 11 tales, composed in the Gurmukhi/Persian vernacular, whose authorship is traditionally attributed to Guru Gobind Singh. It is the last composition of the second scripture of Sikhs, Dasam Granth, and some believe it to be appended to Zafarnamah—the letter to Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.

The history of the Dasam Granth is related to the time of creation and compilation of various writings by Guru Gobind Singh in form of small booklets, some of which are Sikh prayers. The first combined-codex manuscripts of the Dasam Granth were created during the Guru period. It is also said that after 1708, the Dasam Granth was allegedly compiled by Mani Singh Khalsa, contributed by other Khalsa armymen under direct instructions of Mata Sundari and this volume is recognized as Sri Dasam Granth Sahib. The present day Dasam Granth includes Jaap Sahib, Akal Ustat, Bachitar Natak, Chandi Charitar Ukati Bilas, Chandi Charitar II, Chandi di Var, Gyan Prabodh, Chaubis Avtar, Rudra Avtar, 33 Sawaiye, Khalsa Mahima, Shashtar Nam Mala Purana, Ath Pakh-yaan Charitar Likh-yatay and Zafarnamah.

This is a list of works by Indian Punjabi-language writer Bhai Vir Singh (1872–1957). This list includes his poetry, novels, translations, plays, and non-fiction.

The Guru Granth Sahib, is the central religious text of Sikhism, considered by Sikhs to be the final sovereign Guru of the religion. It contains 1430 Angs, containing 5,894 hymns of 36 saint mystics which includes Sikh gurus, Bhagats, Bhatts and Gursikhs. It is notable among foundational religious scriptures for including hymns from writers of other religions, namely Hindus and Muslims. It also contains teachings of the Sikh gurus themselves.

Gurdwara Chowa Sahib is a renovated gurudwara located at the northern edge of the Rohtas Fort, near Jhelum, Pakistan. Situated near the fort's Talaqi gate, the gurdwara commemorates the site where Guru Nanak is popularly believed to have created a water-spring during one of his journeys known as udasi.But parkash of guru granth sahib is not there.

Sewapanthi, alternatively spelt as Sevapanthi, and also known as Addanshahi, is a traditional Sikh sect or order (samparda) that was started by Bhai Kanhaiya, a personal follower of the ninth Sikh Guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur. Kanhaiya was instructed by the Guru to go out and serve humanity, which he did by establishing a Dharmsala in the Attock district of Punjab and serving indiscriminately. Sewa Panthis are also known as 'Addan Shahis'. This name is derived from one of Bhai Kanhaiya's disciples, Addan Shah.

Kavi Santokh Singh was a Sikh historian, poet and writer. He was such a prolific writer that the Sikh Reference Library at Darbar Sahib Amritsar was named after him, located within the Mahakavi Santokh Singh Hall. In addition to "Great Poet" (Mahākavī) Santokh Singh was also referred to as the Ferdowsi of Punjabi literature, Ferdowsi wrote ~50,000 verses while Santokh Singh's Suraj Prakash totals ~52,000. Other scholars have thought of Santokh Singh as akin to Vyasa. Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner in 1883 wrote that, "Santokh Singh of Kantal in the Karnal District, has rendered his name immortal" through the production of his works.

Satta Doom, also spelt as Satta Dum, was a drummer and author of eight verses found within the Guru Granth Sahib.