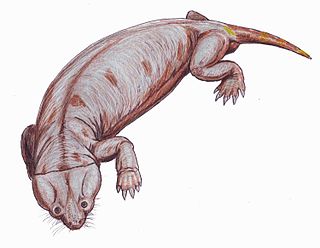

Gorgonopsia is an extinct clade of sabre-toothed therapsids from the Middle to the Upper Permian, roughly between 265 and 252 million years ago. They are characterised by a long and narrow skull, as well as elongated upper and sometimes lower canine teeth and incisors which were likely used as slashing and stabbing weapons. Postcanine teeth are generally reduced or absent. For hunting large prey, they possibly used a bite-and-retreat tactic, ambushing and taking a debilitating bite out of the target, and following it at a safe distance before its injuries exhausted it, whereupon the gorgonopsian would grapple the animal and deliver a killing bite. They would have had an exorbitant gape, possibly in excess of 90°, without having to unhinge the jaw.

Gorgonops is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsid, of which it is the type genus. Gorgonops lived during the Late Permian (Wuchiapingian), about 260–254 million years ago in what is now South Africa.

Inostrancevia is an extinct genus of large carnivorous therapsids which lived during the Late Permian in what are now Siberia, Russia and Southern Africa. The first-known fossils of this gorgonopsian were discovered in the Northern Dvina, where two almost complete skeletons were exhumed. Subsequently, several other fossil materials were discovered in various oblasts, and these finds will lead to a confusion about the exact number of valid species in the country, before only three of them were officially recognized: I. alexandri, I. latifrons and I. uralensis. More recent research carried out in South Africa has discovered fairly well-preserved remains of the genus, being attributed to the species I. africana. An isolated left premaxilla suggests that Inostrancevia also lived in Tanzania during the earliest Lopingian age. The whole genus is named in honor of Alexander Inostrantsev, professor of Vladimir P. Amalitsky, the paleontologist who described the taxon.

Dinogorgon is a genus of gorgonopsid from the Late Permian of South Africa and Tanzania. The generic name Dinogorgon is derived from Greek, meaning "terrible gorgon", while its species name rubidgei is taken from the surname of renowned Karoo paleontologist, Professor Bruce Rubidge, who has contributed to much of the research conducted on therapsids of the Karoo Basin. The type species of the genus is D. rubidgei.

The Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone is a tetrapod assemblage zone or biozone which correlates to the middle Abrahamskraal Formation, Adelaide Subgroup of the Beaufort Group, a fossiliferous and geologically important geological Group of the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. The thickest outcrops, reaching approximately 2,000 metres (6,600 ft), occur from Merweville and Leeu-Gamka in its southernmost exposures, from Sutherland through to Beaufort West where outcrops start to only be found in the south-east, north of Oudshoorn and Willowmore, reaching up to areas south of Graaff-Reinet. Its northernmost exposures occur around the towns Fraserburg and Victoria West. The Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone is the second biozone of the Beaufort Group.

The Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone is a tetrapod assemblage zone or biozone found in the Adelaide Subgroup of the Beaufort Group, a majorly fossiliferous and geologically important geological group of the Karoo Supergroup in South Africa. This biozone has outcrops located in the Teekloof Formation north-west of Beaufort West in the Western Cape, in the upper Middleton and lower Balfour Formations respectively from Colesberg of the Northern Cape to east of Graaff-Reinet in the Eastern Cape. The Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone is one of eight biozones found in the Beaufort Group, and is considered to be Late Permian in age.

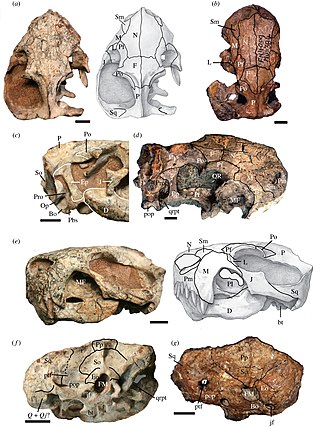

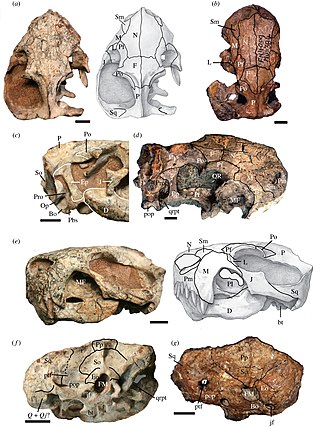

Euchambersia is an extinct genus of therocephalian therapsids that lived during the Late Permian in what is now South Africa and China. The genus contains two species. The type species E. mirabilis was named by paleontologist Robert Broom in 1931 from a skull missing the lower jaw. A second skull, belonging to a probably immature individual, was later described. In 2022, a second species, E. liuyudongi, was named by Jun Liu and Fernando Abdala from a well-preserved skull. It is a member of the family Akidnognathidae, which historically has also been referred by as the synonymous Euchambersiidae.

Moschorhinus is an extinct genus of therocephalian synapsid in the family Akidnognathidae with only one species: M. kitchingi, which has been found in the Late Permian to Early Triassic of the South African Karoo Supergroup. It was a large carnivorous therapsid, reaching 1.1–1.5 metres (3.6–4.9 ft) in total body length with the largest skull comparable to that of a lion in size, and had a broad, blunt snout which bore long, straight canines.

Aelurognathus is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids from the Permian of South Africa and Zambia.

Rubidgea is a genus of gorgonopsian from the upper Permian of South Africa and Tanzania, containing the species Rubidgea atrox. The generic name Rubidgea is sometimes believed to be derived from the surname of renowned Karoo paleontologist, Professor Bruce Rubidge, who has contributed to much of the research conducted on therapsids of the Karoo Basin. However, this generic name was actually erected in honor of Rubidge's paternal grandfather, Sidney Rubidge, who was a renowned fossil hunter. Its species name atrox is derived from Latin, meaning “fierce, savage, terrible”. Rubidgea is part of the gorgonopsian subfamily Rubidgeinae, a derived group of large-bodied gorgonopsians restricted to the Late Permian (Lopingian). The subfamily Rubidgeinae first appeared in the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone. They reached their highest diversity in the Cistecephalus and Daptocephalus assemblage zones of the Beaufort Group in South Africa.

Theriognathus is an extinct genus of therocephalian therapsid belonging to the family Whaitsiidae, known from fossils from South Africa, Zambia, and Tanzania. Theriognathus has been dated as existing during the Late Permian. Although Theriognathus means mammal jaw, the lower jaw is actually made up of several bones as seen in modern reptiles, in contrast to mammals. Theriognathus displayed many different reptilian and mammalian characteristics. For example, Theriognathus had canine teeth like mammals, and a secondary palate, multiple bones in the mandible, and a typical reptilian jaw joint, all characteristics of reptiles. It is speculated that Theriognathus was either carnivorous or omnivorous based on its teeth, and was suited to hunting small prey in undergrowth. This synapsid adopted a sleek profile of a mammalian predator, with a narrow snout and around 1 meter long. Theriognathus is represented by 56 specimens in the fossil record.

Aelurosaurus is a small, carnivorous, extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. It was discovered in the Karoo Basin of South Africa, and first named by Richard Owen in 1881. It was named so because it appeared to be an ancestor for cat-like marsupials, but not yet a mammal itself. It contains five species, A. felinus, A. whaitsi, A. polyodon, A. wilmanae, and A.? watermeyeri. A. felinus, the type species, is generally well described with established features, while the other four species are not due to their poorly preserved holotypes.

Clelandina is an extinct genus of rubidgeine gorgonopsian from the Late Permian of Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone of South Africa. It was first named by Broom in 1948. The type and only species is C. rubidgei. It is relatively rare, with only four known specimens.

Smilesaurus is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian known from South Africa. It lived during the Late Permian. It contains the single species S. ferox.

"Dixeya" nasuta is a extinct species of gorgonopsian that lived during the Late Permian of East Africa, known from fossils found in what is now Tanzania. The species has a complicated taxonomic history, it was originally named as a second species of the genus Dixeya which is now considered a junior synonym of Aelurognathus. "D." nasuta itself, however, was not moved to Aelurognathus, and although it was instead tentatively referred to Arctognathus at first it has since been recognised to not belong to this genus either. This situation leaves "Dixeya" nasuta without a formal genus name. It was proposed to belong to a new distinct genus, named "Njalila", that was informally proposed for the species in a PhD thesis, but this name has not yet been formally published and is currently a nomen nudum. "D." nasuta has been characterised from other gorgonopsians by a combination of its straight snout profile, upturned and "pinched" nose, and curved jaw margin. The fossil record of the Usili Formation shows that the taxon was contemporary with many other gorgonopsians, even alongside large representatives such as Inostrancevia and rubidgeines.

Ictidodraco is an extinct genus of therocephalian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. The type species Ictidodraco longiceps was named by South African paleontologists Robert Broom and John T. Robinson in 1948 from the Cistecephalus Assemblage Zone. Ictidodraco was once classified as a scaloposaurian in the family Silpholestidae. Scaloposauria and Silpholestidae are no longer regarded as valid groups, and Ictidodraco is now classified as a basal member of the clade Baurioidea.

Rubidgeinae is an extinct subfamily of gorgonopsid therapsids known only from Africa. They were among the largest gorgonopsians, and their fossils are common in the Cistecephalus and Daptocephalus assemblage zones of the Karoo Basin. They lived during the Late Permian, and became extinct at the end of the Permian.

Bulbasaurus is an extinct genus of dicynodont that is known from the Lopingian epoch of the Late Permian period of what is now South Africa, containing the type and only species B. phylloxyron. It was formerly considered as belonging to Tropidostoma; however, due to numerous differences from Tropidostoma in terms of skull morphology and size, it has been reclassified the earliest known member of the family Geikiidae, and the only member of the group known from the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone. Within the Geikiidae, it has been placed close to Aulacephalodon, although a more basal position is not implausible.

Nochnitsa is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids who lived during an uncertain stage of the Permian in what is now European Russia. Only one species is known, N. geminidens, described in 2018 from a single specimen including a complete skull and some postcranial remains, discovered in the red beds of Kotelnich, Kirov Oblast. The genus is named in reference to Nocnitsa, a nocturnal creature from Slavic mythology. This name is intended as a parallel to the Gorgons, which are named after many genera among gorgonopsians, as well as for the nocturnal behavior inferred for the animal. The only known specimen of Nochnitsa is one of the smallest gorgonopsians identified to date, with a skull measuring close to 8 cm (3.1 in) in length. The rare postcranial elements indicate that the animal's skeleton should be particularly slender.

Phorcys is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian that lived during the Middle Permian period (Guadalupian) of what is now South Africa. It is known from two specimens, both portions from the back of the skull, that were described and named in 2022 as a new genus and species P. dubei by Christian Kammerer and Bruce Rubidge. Phorcys was recovered from the lowest strata of the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone (AZ) of the Beaufort Group, making it one of the oldest known gorgonopsians in the fossil record—second only to fragmentary remains of an indeterminate specimen from the older underlying Eodicynodon Assemblage Zone. The generic name is from Phorcys of Greek mythology, the father of the Gorgons from which the gorgonopsians are named after, and refers to its status as one of the oldest representatives of the group.