Gorgonopsia is an extinct clade of sabre-toothed therapsids from the Middle to the Upper Permian, roughly between 270 and 252 million years ago. They are characterised by a long and narrow skull, as well as elongated upper and sometimes lower canine teeth and incisors which were likely used as slashing and stabbing weapons. Postcanine teeth are generally reduced or absent. For hunting large prey, they possibly used a bite-and-retreat tactic, ambushing and taking a debilitating bite out of the target, and following it at a safe distance before its injuries exhausted it, whereupon the gorgonopsian would grapple the animal and deliver a killing bite. They would have had an exorbitant gape, possibly in excess of 90°, without having to unhinge the jaw.

Inostrancevia is an extinct genus of large carnivorous therapsids which lived during the Late Permian in what is now European Russia and Southern Africa. The first-known fossils of this gorgonopsian were discovered in the context of a long series of excavations carried out from 1899 to 1914 in the Northern Dvina, Russia. Among these are two near-complete skeletons embodying the first described specimens of this genus, being also the first gorgonopsian identified in Russia. Several other fossil materials were discovered there, and the various finds led to confusion as to the exact number of valid species, before only two of them were formally recognized, namely I. alexandri and I. latifrons. A third species, I. uralensis, was erected in 1974, but the fossil remains of this taxon are very thin and could come from another genus. More recent research carried out in South Africa and Tanzania has discovered specimens identified as belonging to this genus, with the South African specimens being classified within the species I. africana. The genus name honors Alexander Inostrantsev, professor of Vladimir P. Amalitsky, the paleontologist who described the taxon.

Dinogorgon is a genus of gorgonopsid from the Late Permian of South Africa and Tanzania. The generic name Dinogorgon is derived from Greek, meaning "terrible gorgon", while its species name rubidgei is taken from the surname of renowned Karoo paleontologist, Professor Bruce Rubidge, who has contributed to much of the research conducted on therapsids of the Karoo Basin. The type species of the genus is D. rubidgei.

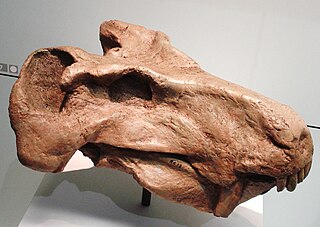

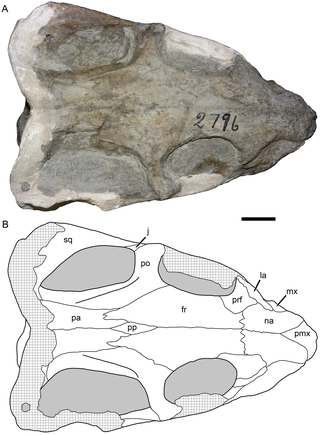

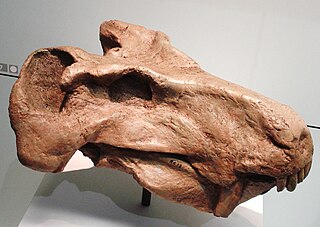

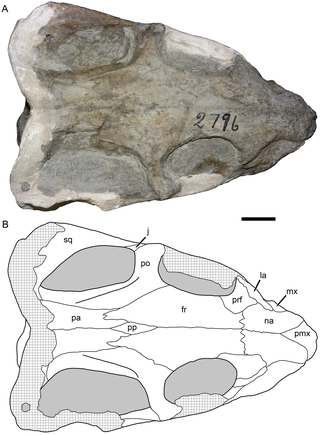

Anteosaurus is an extinct genus of large carnivorous dinocephalian synapsid. It lived at the end of the Guadalupian during the Capitanian age, about 265 to 260 million years ago in what is now South Africa. It is mainly known by cranial remains and few postcranial bones. Measuring 5–6 m (16–20 ft) long and weighing about 600 kg (1,300 lb), Anteosaurus was the largest known carnivorous non-mammalian synapsid and the largest terrestrial predator of the Permian period. Occupying the top of the food chain in the Middle Permian, its skull, jaws and teeth show adaptations to capture large prey like the giants titanosuchids and tapinocephalids dinocephalians and large pareiasaurs.

Viatkogorgon is a genus of gorgonopsian that lived during the Permian period in what is now Russia. The first fossil was found at the Kotelnich locality near the Vyatka River and was made the holotype of the new genus and species V. ivachnenkoi in 1999. The generic name refers to the river and the related genus Gorgonops—the gorgons of Greek mythology are often referenced in the names of the group. The specific name honors the paleontologist Mikhail F. Ivakhnenko. The holotype skeleton is one of the most complete gorgonopsian specimens known and includes rarely preserved elements such as gastralia and a sclerotic ring. A larger, but poorly preserved specimen has also been assigned to the species.

Rubidgea is a genus of gorgonopsian from the upper Permian of South Africa and Tanzania, containing the species Rubidgea atrox. The generic name Rubidgea is sometimes believed to be derived from the surname of renowned Karoo paleontologist, Professor Bruce Rubidge, who has contributed to much of the research conducted on therapsids of the Karoo Basin. However, this generic name was actually erected in honor of Rubidge's paternal grandfather, Sidney Rubidge, who was a renowned fossil hunter. Its species name atrox is derived from Latin, meaning “fierce, savage, terrible”. Rubidgea is part of the gorgonopsian subfamily Rubidgeinae, a derived group of large-bodied gorgonopsians restricted to the Late Permian (Lopingian). The subfamily Rubidgeinae first appeared in the Tropidostoma Assemblage Zone. They reached their highest diversity in the Cistecephalus and Daptocephalus assemblage zones of the Beaufort Group in South Africa.

Lemurosaurus is a genus of extinct biarmosuchian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. The generic epithet Lemursaurus is a mix of Latin, lemures “ghosts, spirits”, and Greek, sauros, “lizard”. Lemurosaurus is easily identifiable by its prominent eye crests, and large eyes. The name Lemurosaurus pricei was coined by paleontologist Robert Broom in 1949, based on a single small crushed skull, measured at approximately 86 millimeters in length, found on the Dorsfontein farm in Graaff-Reinet. To date, only two skulls of the Lemurosaurus have been discovered, so body size is unknown. The second larger, more intact, skull was found in 1974 by a team from the National Museum, Bloemfontein.

Styracocephalus platyrhynchus is an extinct genus of dinocephalian therapsid that existed during the mid-Permian throughout South Africa, but mainly in the Karoo Basin. It is often referred to by its single known species Styracocephalus platyrhynchus. The Dinocephalia clade consisted of the largest land vertebrates and herbivores during the early to mid-Permian. This period is often also referred to as the Guadalupian epoch, approximately 270 to 260 million years ago.

Aelurosaurus is a small, carnivorous, extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. It was discovered in the Karoo Basin of South Africa, and first named by Richard Owen in 1881. It was named so because it appeared to be an ancestor for cat-like marsupials, but not yet a mammal itself. It contains five species, A. felinus, A. whaitsi, A. polyodon, A. wilmanae, and A.? watermeyeri. A. felinus, the type species, is generally well described with established features, while the other four species are not due to their poorly preserved holotypes.

Scylacops is an extinct genus of Gorgonopsia. It was first named by Broom in 1913, and contains two species, S. bigendens, and S. capensis. Its fossils have been found in South Africa and Zambia. It is believed to be closely related to the Gorgonopsian Sauroctonus progressus. Scylacops was a moderately sized Gorgonopsid.

Eriphostoma is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids known from the Middle Permian of Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone, South Africa. It has one known species, Eriphostoma microdon, and was first named by Robert Broom in 1911. It is the oldest known gorgonopsian and among the smallest and most basal members of the clade.

Scymnosaurus is a dubious genus of therocephalian therapsids based upon various fossils of large early therocephalians. The genus was described by Robert Broom in 1903 with S. ferox, followed by S. watsoni in 1915 and a third, S. major, by Lieuwe Dirk Boonstra in 1954. Each of these species are considered nomen dubia today and based upon specimens belonging to two separate families of therocephalians. S. ferox and S. major represent specimens of Lycosuchidae incertae sedis, while S. watsoni is Scylacosauridae incertae sedis. Broom named a fourth species in 1907 from KwaZulu-Natal, S. warreni, though he later referred it to Moschorhinus as a valid species in 1932 but now is recognised as being synonymous with M. kitchingi.

Trochosuchus is a dubious genus of therocephalian therapsid from the middle Permian (Capitanian) of South Africa based on a weathered and poorly preserved undiagnostic fossil of a lycosuchid therocephalian. It includes the type and only species, T. acutus. Trochosuchus was named by palaeontologist Robert Broom in 1908 based on its supposedly unique proportions of the simulatenous 'double' functional canines thought to be characteristic of lycosuchids, with the pair in front being noticeably smaller than the second pair behind.

"Dixeya" nasuta is an extinct species of gorgonopsian that lived during the Late Permian of East Africa, known from fossils found in what is now Tanzania. The species has a complicated taxonomic history, it was originally named as a second species of the genus Dixeya which is now considered a junior synonym of Aelurognathus. "D." nasuta itself, however, was not moved to Aelurognathus, and although it was instead tentatively referred to Arctognathus at first it has since been recognised to not belong to this genus either. This situation leaves "Dixeya" nasuta without a formal genus name. It was proposed to belong to a new distinct genus, named "Njalila", that was informally proposed for the species in a PhD thesis, but this name has not yet been formally published and is currently a nomen nudum. "D." nasuta has been characterised from other gorgonopsians by a combination of its straight snout profile, upturned and "pinched" nose, and curved jaw margin. The fossil record of the Usili Formation shows that the taxon was contemporary with many other gorgonopsians, even alongside large representatives such as Inostrancevia and rubidgeines.

Blattoidealestes is a dubious genus of therocephalian, an extinct therapsid from the Middle Permian of South Africa. The type species Blattoidealestes gracilis was named by South African paleontologist Lieuwe Dirk Boonstra from the Tapinocephalus Assemblage Zone in 1954. Dating back to the Middle Permian, Blattoidealestes is one of the oldest therocephalians. It is similar in appearance to the small therocephalian Perplexisaurus from Russia, and may be closely related.

Simorhinella is an extinct genus of therocephalian therapsids from the Late Permian of South Africa. It is known from a single species, Simorhinella baini, named by South African paleontologist Robert Broom in 1915. Broom named it on the basis of a single fossil collected by the British Museum of Natural History in 1878 that included the skull and jaws from the eye sockets forward. The skull is unusual in that it has an extremely short and deep snout, unlike the longer and lower snouts of most other therocephalians. Because of the skull's distinctiveness, the classification of Simorhinella within Therocephalia based on the holotype was deemed to be uncertain. However, a 2014 study describing the skull of a much larger therocephalian identified the new specimen as an adult of Simorhinella, based on a bony crest on the vomer of the palate found in both specimens. Based on its anatomy, they proposed that Simorhinella was closely related to the basal therocephalian Lycosuchus and placed it in the family Lycosuchidae.

Nochnitsa is an extinct genus of gorgonopsian therapsids who lived during an uncertain stage of the Permian in what is now European Russia. Only one species is known, N. geminidens, described in 2018 from a single specimen including a complete skull and some postcranial remains, discovered in the red beds of Kotelnich, Kirov Oblast. The genus is named in reference to Nocnitsa, a nocturnal creature from Slavic mythology. This name is intended as a parallel to the Gorgons, which are named after many genera among gorgonopsians, as well as for the nocturnal behavior inferred for the animal. The only known specimen of Nochnitsa is one of the smallest gorgonopsians identified to date, with a skull measuring close to 8 cm (3.1 in) in length. The rare postcranial elements indicate that the animal's skeleton should be particularly slender.

Thliptosaurus is an extinct genus of small kingoriid dicynodont from the latest Permian period of the Karoo Basin in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. It contains the type and only known species T. imperforatus. Thliptosaurus is from the upper Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone, making it one of the youngest Permian dicynodonts known, living just prior to the Permian mass extinction. It also represents one of the few small bodied dicynodonts to exist at this time, when most other dicynodonts had large body sizes and many small dicynodonts had gone extinct. The unexpected discovery of Thliptosaurus in a region of the Karoo outside of the historically sampled localities suggests that it may have been part of an endemic local fauna not found in these historic sites. Such under-sampled localities may contain 'hidden diversities' of Permian faunas that are unknown from traditional samples. Thliptosaurus is also unusual for dicynodonts as it lacks a pineal foramen, suggesting that it played a much less important role in thermoregulation than it did for other dicynodonts.

Vetusodon is an extinct genus of cynodonts belonging to the clade Epicynodontia. It contains one species, Vetusodon elikhulu, which is known from four specimens found in the Late Permian Daptocephalus Assemblage Zone of South Africa. With a skull length of about 18 centimetres (7.1 in), Vetusodon is the largest known cynodont from the Permian. Through convergent evolution, it possessed several unusual features reminiscent of the contemporary therocephalian Moschorhinus, including broad, robust jaws, large incisors and canines, and small, single-cusped postcanine teeth.

Nyaphulia is an extinct genus of dicynodont therapsid from the middle Permian of South Africa, containing only the type species N. oelofseni. The generic name is in honour of John Nyaphuli of the National Museum of Bloemfontein, who contributed extensively to South African palaeontology and discovered the holotype specimen of Nyaphulia in 1982. Nyaphulia was initially named as a second species of the basal dicynodont Eodicynodon by Professor Bruce Rubidge in 1990 as E. oelofseni, named after his mentor in palaeontology and geology Dr. Burger Oelofsen.