The Philippine Independent Church, officially referred to by its Spanish name Iglesia Filipina Independiente (IFI) and colloquially called the Aglipayan Church, is an independent Christian denomination, in the form of a nationalist church, in the Philippines. Its nationalist schism from the Roman Catholic Church was proclaimed during the American colonial period in 1902, following the end of the Philippine–American War, by members of the Unión Obrera Democrática Filipina due to the pronounced mistreatment of Filipinos by Spanish priests and partly influenced by the unjust executions of José Rizal and Filipino priests and prominent secularization movement figures Mariano Gomez, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, during earlier Spanish colonial rule when Roman Catholicism was the state religion in the country.

Gregorio Aglipay Cruz y Labayán was a Filipino former Roman Catholic priest and revolutionary during the Philippine Revolution and Philippine–American War who became the first head of the Iglesia Filipina Independiente (IFI), the first-ever wholly Filipino-led independent Christian Church in the Philippines in the form of a nationalist church.

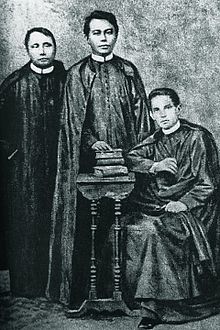

José Apolonio Burgos y García was a Filipino Catholic priest, accused of mutiny by the Spanish colonial authorities in the Philippines in the 19th century. He was tried and executed in Manila along with two other clergymen, Mariano Gomez and Jacinto Zamora, who are collectively known as the Gomburza.

Gomburza, alternatively stylized as GOMBURZA or GomBurZa. "Gom" meaning Gómes, "Bur" meaning Burgos, and "Za" for Zamora. <refname="remembering-the-MaJohan ">Agbayani III, Eufemio O.. "Remembering the GOMBURZA throughout the Years". National Historical Commission of the Philippines. Retrieved August 31, 2022.</ref> refers to three Filipino Catholic priests, Mariano Gómes, José Burgos, and Jacinto Zamora, who were executed by a garrote on February 17, 1872, in Bagumbayan, Philippines by Spanish colonial authorities on charges of subversion arising from the 1872 Cavite mutiny. The name is a portmanteau of the priests' surnames.

The Archdiocese of Manila is the archdiocese of the Latin Church of the Catholic Church in Metro Manila, Philippines, encompassing the cities of Manila, Makati, San Juan, Mandaluyong, Pasay, Taguig, and Quezon City. Its cathedral is the Minor Basilica and Metropolitan Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, also known as the Manila Cathedral, located in Intramuros, which comprises the old city of Manila. The Blessed Virgin Mary, under the title Immaculate Conception, is the principal patroness of the archdiocese.

Freedom of religion in the Philippines is guaranteed by the Constitution of the Philippines.

As part of the worldwide Catholic Church, the Catholic Church in the Philippines, or the Philippine Catholic Church, is part of the worldwide Catholic Church, under the spiritual leadership of the Pope in Rome. The Philippines is one of the two nations in Asia having a substantial portion of the population professing the Catholic faith, along with East Timor, and has the third largest Catholic population in the world after Brazil and Mexico. The episcopal conference responsible in governing the faith is the Catholic Bishops' Conference of the Philippines (CBCP).

In Christianity, the term secular clergy refers to deacons and priests who are not monastics or otherwise members of religious life. Secular priests are priests who commit themselves to a certain geographical area and are ordained into the service of the residents of a diocese or equivalent church administrative region. That includes serving the everyday needs of the people in parishes, but their activities are not limited to that of their parish.

The Order of Augustinian Recollects (OAR) is a mendicant Catholic religious order of friars and nuns. It is a reformist offshoot from the Augustinian hermit friars and follows the same Rule of St. Augustine. They have also been known as the "Discalced Augustinians".

The Cavite mutiny was an uprising of Filipino military personnel of Fort San Felipe, the Spanish arsenal in Cavite, Philippine Islands on January 20, 1872. Around 200 locally recruited colonial troops and laborers rose up in the belief that it would elevate to a national uprising. The mutiny was unsuccessful, and government soldiers executed many of the participants and began to crack down on a burgeoning Philippines nationalist movement. Many scholars believed that the Cavite mutiny was the beginning of Filipino nationalism that would eventually lead to the Philippine Revolution.

Mariano Gómes de los Ángeles, often known by his birth name Mariano Gómez y Custodio or Mariano Gomez in modern orthography, was a Filipino Catholic priest who was falsely accused of mutiny by the Spanish colonial authorities in the Philippines in the 19th century. He was placed in a mock trial and summarily executed in Manila along with two other clergymen collectively known as the Gomburza. Gomes was the oldest of the three priests and spent his life writing about abuses against Filipino priests.

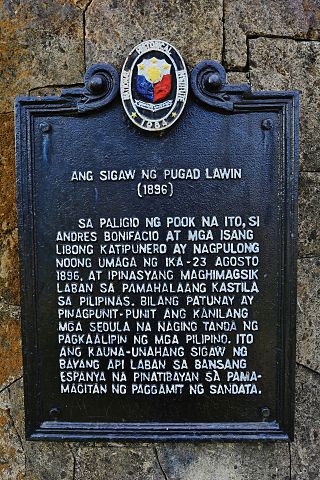

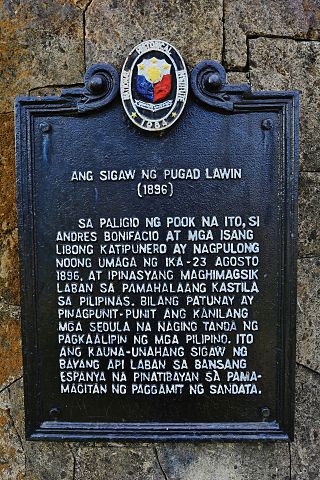

The Cry of Pugad Lawin was the beginning of the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish Empire.

The Philippine Propaganda Movement encompassed the activities of a group based in Spain but coming from the Philippines, composed of Indios, Mestizos, Insulares and Peninsulares who called for political reforms in the Philippines in the late 19th century, and produced books, leaflets, and newspaper articles to educate others about their goals and issues they were trying to solve. They were active approximately from 1880 to 1898, and especially between 1880 and 1895, before the Philippine Revolutionary War against Spain began.

Pedro Peláez y Sebastián was a Filipino Catholic priest who favored the rights for Filipino clergy during the 19th century. He was diocesan administrator of the Archdiocese of Manila for a brief period of time. In the early 19th century, Pelaez advocated for the secularization of Filipino priests and is considered the "Godfather of the Philippine Revolution." His cause towards beatification has been initiated; he is designated with the title "Servant of God."

The Augustinian Recollect Province of Saint Ezequiél Moreno is a division of the Order of Augustinian Recollects that has jurisdiction over the Philippines, Taiwan and Sierra Leone. It officially separated from the Province of Saint Nicholas de Tolentine on 28 November 1998. Today, the Provincialate House is located at the San Nicolas De Tolentino Parish Church on Neptune Street, Congressional Subdivision, Project 6, Quezon City.

Máximo F. Inocencio was a Filipino architect and businessman involved in construction, shipping, trade and lumber. He figured in the 1872 Cavite mutiny and was a financial supporter of the Philippine Revolution, leading to his execution by the Spaniards in 1896. Consequently, he and the other Filipinos executed came to be known as the Thirteen Martyrs of Cavite.

The Immaculate Conception Parish Church, also known as the Dasmariñas Church, is the first Roman Catholic parish church in the city of Dasmariñas, province of Cavite, Philippines. It is under the jurisdiction of the Diocese of Imus. The stone church was constructed right after the establishment of Dasmariñas as a separate parish in 1866. The church and convent was the site of bloodshed during the Battle of Perez Dasmari ñas of the Philippine revolution against Spain. It was declared as an important historical structure by the National Historical Institute with the placing of a historical marker in 1986.

José Julián de Aranguren was a young Spanish Augustinian missionary when he was sent to the Philippines in 1829. He became the 22nd Archbishop of the Philippine archdiocese of the Latin branch of the Catholic Church serving from 1847 to 1861.

GomBurZa is a 2023 Philippine historical biographical film co-written and directed by Pepe Diokno. Starring Dante Rivero, Cedrick Juan, and Enchong Dee, it features and follows the lives of the Gomburza, three native Filipino Roman Catholic priests executed during the latter years of the Spanish colonial era in the Philippines.