| Athlete | Country | Sport | Games | Medal(s) | Details | Regulations and verification |

|---|

| Stanisława Walasiewicz (a.k.a. Stella Walsh) ‡ |  Poland Poland | Athletics | 1932, 1936 |   | Won a gold medal in 1932 and a silver medal in 1936. An autopsy discovered that Walsh was intersex and experienced mosaicism; it was determined she likely did not know, and her achievements have not been expunged. [15] [17] [50] [51] [52] [1] | There were no formal regulations before 1936; from 1936, the IOC was able to examine athletes whose sex was questioned. [2] Anecdotally, Walsh's rival Helen Stephens reported that in 1936, Adolf Hitler personally groped her as a form of sex verification. [16] |

| Heinrich Ratjen † |  Nazi Germany Nazi Germany | Athletics | 1936 | | Ratjen's sex characteristics were ambiguous from birth. Though he was raised as female, and for many years competed as "Dora Ratjen" (including at the Olympics), he said he was conscious that he was somewhat biologically male from childhood. In 1938, he was arrested and held in Hohenlychen Sanatorium for a year, being examined by SS doctors who found Ratjen to have some intersex characteristics (not just male genitalia). Upon release, he was ordered to stop participating in sport and to assume a male identity. In later life, however, Ratjen (likely erroneously) claimed that the Nazis had ordered him to pose as female in order to bring sporting glory to the nation at their home Olympics. [18] [53] [54] [19] | From 1936, the IOC was able to examine athletes whose sex was questioned. [2] After years of speculation and reportedly refusing to use changing rooms with other people present, Ratjen was accosted on a train and made to strip before being arrested. [18] |

| Erik Schinegger † |  Austria Austria | Alpine skiing | 1968 [d] | | Schinegger was raised as Erika and competed in skiing as a woman until 1968, when his intersex condition was discovered. He was removed from participation, [19] going on to live as a man and father a child. [55] He was not retroactively stripped of his 1966 World Championship title, but the original runner-up Marielle Goitschel was retroactively awarded the gold medal as well. In 1988 Schinegger himself presented his World Championship gold medal to Goitschel, [56] though she gave it back to him. [57] | Formal medical testing, using the X-Chromatin test, was first trialled by the IOC at the 1968 Winter Olympics, before being implemented at the 1968 Summer Olympics. [19] |

| Nancy Navalta † |  Philippines Philippines | Athletics | 1996 [d] | | Navalta was named part of the Philippines' delegation for the 1996 Summer Olympics after attaining a qualifying time. However her career ended after she learned about her intersex condition in 1996 and she was removed from the team. [27] | In 1992, the majority of the sports federations under the IOC stopped performing any type of gender testing, and the IOC itself replaced the chromosome testing with a DNA-based test. This test was carried out on all female athletes in 1996. [58] |

| Edinanci Silva Δ |  Brazil Brazil | Judo | 1996, 2000, 2004, 2008 | | Silva was born intersex but had surgery in the 1990s to allow her to compete in women's sport, before any Olympics appearance. She went on to compete at four Games. [59] [1] | In 1992, the majority of the sports federations under the IOC stopped performing any type of gender testing. Judo was one of the five federations that continued testing, and the IOC itself replaced the chromosome testing with a DNA-based test. This test was carried out on all female athletes in 1996. In 1999, the IOC stopped universal testing but reserved the right to test suspicious individuals. [58] The same test was used up to and including the 2008 Summer Olympics, but only when suspicions were raised. Athletes who had undergone "sex reassignment surgery" were allowed to compete, two years after surgery and meeting all other requirements. [1] |

| Érika Coimbra Δ |  Brazil Brazil | Volleyball | 2000, 2004 |  | Coimbra was reported to have been born intersex but had surgery. She was subject to sex testing before being allowed to compete. [60] [61] | In 1992, the majority of the sports federations under the IOC stopped performing any type of gender testing. [58] Volleyball was one of the five federations that continued testing, [62] and the IOC itself replaced the chromosome testing with a DNA-based test. In 1999, the IOC stopped universal testing but reserved the right to test suspicious individuals. [58] The same test was used up to and including the 2008 Summer Olympics, but only when suspicions were raised. Athletes who had undergone "sex reassignment surgery" were allowed to compete, two years after surgery and meeting all other requirements. [1] |

| Francine Niyonsaba Δ |  Burundi Burundi | Athletics | 2012, 2016, 2020 |  | Niyonsaba won silver in the 800 m race in 2016; unable to contest this event at the 2020 Games due to restrictions, she qualified and competed in the 10,000 m race. [63] Her intersex condition was revealed upon the ruling in 2019. [64] | In 2012, the IOC introduced testing based on measuring testosterone. [5]

Ahead of qualifying for the 2016 Summer Olympics, the IAAF was forced to suspend testosterone testing until at least 2017 due to losing a case brought by Dutee Chand. The IOC updated its policy around the same time and, in 2016, said they would also suspend testosterone testing while the IAAF was trying to support the tests. [65]

In 2019, World Athletics (IAAF) banned female athletes from competing in middle-distance running events and some others [e] if they: - have an XY karyotype and

- have ≥5 nmol/L testosterone and

- do not have androgen insensitivity

|

| Caster Semenya Δ |  South Africa South Africa | Athletics | 2012, 2016 |   | Semenya is an intersex woman with XY chromosomes. She has been subject to sex verification testing since the start of her professional career in 2009, at different times being allowed and disallowed to compete in events. A successful intersex sportswoman, she has been the focal point of debates and regulation regarding both intersex and trans athletes in the 21st century. She has refused to take hormone medication to reduce her natural testosterone, as instructed in 2019. [67] [38] She continues to mount legal battles against discriminatory athletic bodies. [68] |

| Dutee Chand Δ |  India India | Athletics | 2016, 2020 | | Chand experiences hyperandrogenism. [69] [70] In 2014, her elevated testosterone caused the Indian Athletics Federation to remove her from its programme and ban her from events. She appealed to higher athletic bodies, which overturned the ban. [71] [72] [73] As a sprinter, she was unaffected by the 2019 restrictions on intersex characteristics in middle distance events; she offered the services of her legal team to Caster Semenya. [74] |

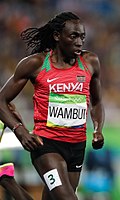

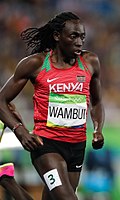

| Margaret Wambui † |  Kenya Kenya | Athletics | 2016 |  | Wambui has elevated testosterone levels, as revealed upon the intersex restriction ruling in 2019; refusing to take medication to reduce this, she was barred from competing in the 2020 Games. She has proposed athletic bodies introduce an open category to be inclusive of intersex athletes if they insist on the separation. [63] [64] [75] | Ahead of qualifying for the 2016 Summer Olympics, the IAAF was forced to suspend testosterone testing until at least 2017 due to losing a case brought by Dutee Chand. The IOC updated its policy around the same time and, in 2016, said they would also suspend testosterone testing while the IAAF was trying to support the tests. [65]

In 2019, World Athletics (IAAF) banned female athletes from competing in middle-distance running events and some others [e] if they: - have an XY karyotype and

- have ≥5 nmol/L testosterone and

- do not have androgen insensitivity

|

| Beatrice Masilingi Δ |  Namibia Namibia | Athletics | 2020 | | Condition announced by World Athletics ahead of appearing at the 2020 Games. [76] The Namibia National Olympic Committee criticised World Athletics for breaking a confidentiality agreement in naming teenage sprinters Beatrice Masilingi and Christine Mboma, who could (and would) both compete over a different distance. [77] | In 2019, World Athletics (IAAF) banned female athletes from competing in middle-distance running events and some others [e] if they: - have an XY karyotype and

- have ≥5 nmol/L testosterone and

- do not have androgen insensitivity

|

| Christine Mboma Δ |  Namibia Namibia | Athletics | 2020 |  |

| Aminatou Seyni Δ |  Niger Niger | Athletics | 2020 | | Seyni primarily contests sprint distances, but also ran 800 m sporadically and 400 m regularly until 2019, when she was told she had tested positive for intersex characteristics and would be unable to race middle distance. She ran in the 200 m event, a distance over which she holds the Nigerien national record, at the 2020 Games. [63] [78] |

| Pedro Spajari Δ |  Brazil Brazil | Swimming | 2020 | | Having broken the FINA World Junior Championship record for 100 m freestyle in 2015, [79] Spajari was diagnosed with Klinefelter syndrome, an XXY chromosomal condition in natural men, in 2016. He was aiming to qualify for that year's Games when decreased testosterone levels, which negatively affected his performances, was noticed. He was approved to take hormone supplements, and competed in 2020. [80] [81] | Sex verification is not conducted on athletes in the men's categories. [82] If a male athlete's performance is considered suspicious, doping controls are used. [42] |