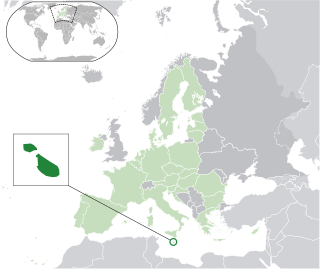

In law, sex characteristic refers to an attribute defined for the purposes of protecting individuals from discrimination due to their sexual features. The attribute of sex characteristics was first defined in national law in Malta in 2015. The legal term has since been adopted by United Nations, European, and Asia-Pacific institutions, and in a 2017 update to the Yogyakarta Principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression and sex characteristics.

Intersex Human Rights Australia (IHRA) is a voluntary organisation for intersex people that promotes the human rights and bodily autonomy of intersex people in Australia, and provides education and information services. Established in 2009 and incorporated as a charitable company in 2010, it was formerly known as Organisation Intersex International Australia, or OII Australia. It is recognised as a Public Benevolent Institution.

Intersex civil society organizations have existed since at least the mid-1980s. They include peer support groups and advocacy organizations active on health and medical issues, human rights, legal recognition, and peer and family support. Some groups, including the earliest, were open to people with specific intersex traits, while others are open to people with many different kinds of intersex traits.

The International Intersex Forum is an annual event organised, then later supported, by the ILGA and ILGA-Europe that and organisations from multiple regions of the world, and it is believed to be the first and only such intersex event.

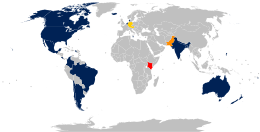

Human Rights between the Sexes is an analysis of the human rights of intersex people in 12 countries. It was written by Dan Christian Ghattas of the Internationalen Vereinigung Intergeschlechtlicher Menschen and published in October 2013 by the Heinrich Böll Foundation. The countries studied were Australia, Belgium, France, Germany, New Zealand, Serbia, South Africa, Taiwan, Turkey, Uganda, Ukraine and Uruguay.

Zwischengeschlecht is a human rights advocacy group campaigning on intersex bodily autonomy issues. The group demonstrates outside medical events where surgical interventions are discussed or performed, engages with the media, and participates in consultations with human rights institutions.

Dan Christian Ghattas is an intersex activist, university lecturer and author who co-founded OII Europe in 2012 and is now executive director. In 2013, he authored Human Rights between the Sexes, a first comparative international analysis of the human rights situation of intersex people.

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, or genitals, that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies."

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, or genitals that, according to the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies".

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, or genitals that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies". "Because their bodies are seen as different, intersex children and adults are often stigmatized and subjected to multiple human rights violations".

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics that "do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies". They are substantially more likely to identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) than endosex people. According to a study done in Australia of Australian citizens with intersex conditions, participants labeled 'heterosexual' as the most popular single label with the rest being scattered among various other labels. According to another study, an estimated 8.5% to 20% experiencing gender dysphoria. Although many intersex people are heterosexual and cisgender, and not all of them identify as LGBTQ+, this overlap and "shared experiences of harm arising from dominant societal sex and gender norms" has led to intersex people often being included under the LGBT umbrella, with the acronym sometimes expanded to LGBTI. Some intersex activists and organisations have criticised this inclusion as distracting from intersex-specific issues such as involuntary medical interventions.

The following is a timeline of intersex history.

Intersex rights in Australia are protections and rights afforded to intersex people through statutes, regulations, and international human rights treaties, including through the Sex Discrimination Act 1984 (Cth) which makes it unlawful to discriminate against a person based upon that person's intersex status in contexts such as work, education, provision of services, and accommodation.

The Malta declaration is the statement of the Third International Intersex Forum, which took place in Valletta, Malta, in 2013. The event was supported by the ILGA and ILGA-Europe and brought together 34 people representing 30 organisations from multiple regions of the world.

Intersex rights in Malta since 2015 are among the most progressive in the world. Intersex children in Malta have world-first protections from non-consensual cosmetic medical interventions, following the passing into law of the Gender Identity, Gender Expression and Sex Characteristics Act in 2015. All Maltese intersex persons have protection from discrimination. Individuals who seek it can access simple administrative methods of changing sex assignment, with binary and non-binary forms of identification available.

Intersex people in the United Kingdom face significant gaps in legal protections, particularly in protection from non-consensual medical interventions, and protection from discrimination. Actions by intersex civil society organisations aim to eliminate unnecessary medical interventions and harmful practices, promote social acceptance, and equality in line with Council of Europe and United Nations demands. Intersex civil society organisations campaign for greater social acceptance, understanding of issues of bodily autonomy, and recognition of the human rights of intersex people.

Intersex people in France face significant gaps in protection from non-consensual medical interventions and protection from discrimination. The birth of Abel Barbin, a nineteenth-century intersex woman, is marked in Intersex Day of Remembrance. Barbin may have been the first intersex person to write a memoir, later published by Michel Foucault.

Intersex people are born with sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, hormones, or genitals that, according to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, "do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies". Such variations may involve genital ambiguity, and combinations of chromosomal genotype and sexual phenotype other than XY-male and XX-female.

Intersex people in Argentina have no recognition of their rights to physical integrity and bodily autonomy, and no specific protections from discrimination on the basis of sex characteristics. Cases also exist of children being denied access to birth certificates without their parents consenting to medical interventions. The National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism and civil society organizations such as Justicia Intersex have called for the prohibition of unnecessary medical interventions and access to redress.

Intersex people in Switzerland have no recognition of rights to physical integrity and bodily autonomy, and no specific protections from discrimination on the basis of sex characteristics. In 2012, the Swiss National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics published a report on the medical management of differences of sex development or intersex variations.