Space Exploration Technologies Corp. (SpaceX) is an American aerospace manufacturer, space transportation services and communications corporation headquartered in Hawthorne, California. SpaceX was founded in 2002 by Elon Musk with the goal of reducing space transportation costs to enable the colonization of Mars. SpaceX manufactures the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launch vehicles, several rocket engines, Dragon cargo, crew spacecraft and Starlink communications satellites.

Launch Complex 39A (LC-39A) is the first of Launch Complex 39's two launch pads, located at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Merritt Island, Florida. The pad, along with Launch Complex 39B, were first designed for the Saturn V launch vehicle, which is still the United States' most powerful rocket. Typically used to launch NASA's crewed spaceflight missions since the late 1960s, the pad was leased by SpaceX and has been modified to support their launch vehicles.

Launch Complex 39 (LC-39) is a rocket launch site at the John F. Kennedy Space Center on Merritt Island in Florida, United States. The site and its collection of facilities were originally built as the Apollo program's "Moonport" and later modified for the Space Shuttle program.

Falcon 9 is a partially reusable two-stage-to-orbit medium-lift launch vehicle designed and manufactured by SpaceX in the United States. The latest version of the first stage can return to Earth and be flown again multiple times. Both the first and second stages are powered by SpaceX Merlin engines, using cryogenic liquid oxygen and rocket-grade kerosene (RP-1) as propellants. Its name is derived from the fictional Star Wars spacecraft, the Millennium Falcon, and the nine Merlin engines of the rocket's first stage. The rocket evolved with versions v1.0 (2010–2013), v1.1 (2013–2016), v1.2 Full Thrust (2015–present), including the Block 5 Full Thrust variant, flying since May 2018. Unlike most rockets in service, which are expendable launch systems, since the introduction of the Full Thrust version, Falcon 9 is partially reusable, with the first stage capable of re-entering the atmosphere and landing vertically after separating from the second stage. This feat was achieved for the first time on flight 20 in December 2015. Since then, SpaceX has successfully landed boosters dozens of times, with individual first stages flying as many as ten times.

Space Launch Complex 40 (SLC-40), previously Launch Complex 40 (LC-40) is a launch pad for rockets located at the north end of Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, Florida.

Vertical takeoff, vertical landing (VTVL) is a form of takeoff and landing for rockets. Multiple VTVL craft have flown. The most widely known and commercially successful VTVL rocket is SpaceX's Falcon 9 first stage.

Launch Complex 13 (LC-13) was a launch complex at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, the third-most southerly of the original launch complexes known as Missile Row, lying between LC-12 and LC-14. In 2015, the LC-13 site was leased by SpaceX and was renovated for use as Landing Zone 1 and Landing Zone 2, the company's East Coast landing location for returning Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launch vehicle booster stages.

Falcon 9 prototypes were experimental flight test reusable rockets that performed vertical takeoffs and landings. The project was privately funded by SpaceX, with no funds provided by any government until later on. Two prototypes were built, and both were launched from the ground.

SpaceX manufactures launch vehicles to operate its launch provider services and to execute its various exploration goals. SpaceX currently manufactures and operates the Falcon 9 Full Thrust family of medium-lift launch vehicles and the Falcon Heavy family of heavy-lift launch vehicles – both of which powered by SpaceX Merlin engines and employing VTVL technologies to reuse the first stage. As of 2020, the company is also developing the fully reusable Starship launch system, which will replace the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy.

The SpaceX reusable launch system development program is a privately funded program to develop a set of new technologies for an orbital launch system that may be reused many times in a manner similar to the reusability of aircraft. SpaceX has been developing the technologies over several years to facilitate full and rapid reusability of space launch vehicles. The project's long-term objectives include returning a launch vehicle first stage to the launch site in minutes and to return a second stage to the launch pad following orbital realignment with the launch site and atmospheric reentry in up to 24 hours. SpaceX's long term goal is that both stages of their orbital launch vehicle will be designed to allow reuse a few hours after return.

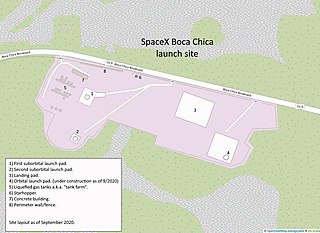

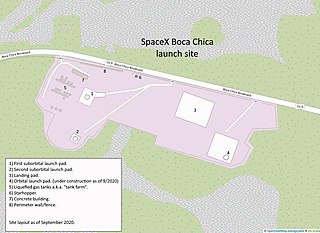

The SpaceX South Texas launch site, referred to by SpaceX as Starbase, and also known as the Boca Chica launch site, is a private rocket production facility, test site, and spaceport constructed by SpaceX, located at Boca Chica approximately 32 km (20 mi) east of Brownsville, Texas, on the US Gulf Coast. When conceptualized, its stated purpose was "to provide SpaceX an exclusive launch site that would allow the company to accommodate its launch manifest and meet tight launch windows." The launch site was originally intended to support launches of the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launch vehicles as well as "a variety of reusable suborbital launch vehicles", but in early 2018, SpaceX announced a change of plans, stating that the launch site would be used exclusively for SpaceX's next-generation launch vehicle, Starship. Between 2018 and 2020, the site added significant rocket production and test capacity. SpaceX CEO Elon Musk indicated in 2014 that he expected "commercial astronauts, private astronauts, to be departing from South Texas," and he foresaw launching spacecraft to Mars from the site.

Falcon 9 v1.1 was the second version of SpaceX's Falcon 9 orbital launch vehicle. The rocket was developed in 2011–2013, made its maiden launch in September 2013, and its final flight in January 2016. The Falcon 9 rocket was fully designed, manufactured, and operated by SpaceX. Following the second Commercial Resupply Services (CRS) launch, the initial version Falcon 9 v1.0 was retired from use and replaced by the v1.1 version.

The Dragon 2 DragonFly was a prototype suborbital rocket-powered test vehicle for a propulsively-landed version of the SpaceX Dragon 2. DragonFly underwent testing in Texas at the McGregor Rocket Test Facility in October 2015. However, the development eventually ceased as the verification burden imposed by NASA was too great to justify it.

The Falcon 9 first-stage landing tests were a series of controlled-descent flight tests conducted by SpaceX between 2013 and 2016. Since 2017, the first stage of Falcon 9 missions has been routinely landed if the rocket performance allowed it, and if SpaceX chose to recover the stage.

Falcon 9 Full Thrust is a partially reusable medium-lift launch vehicle, designed and manufactured by SpaceX. Designed in 2014–2015, Falcon 9 Full Thrust began launch operations in December 2015. As of 15 September 2021, Falcon 9 Full Thrust had performed 106 launches without any failures. Based on the Lewis point estimate of reliability, this rocket is the most reliable orbital launch vehicle currently in operation.

Landing Zone 1 and Landing Zone 2, also known as LZ-1 and LZ-2 respectively, are landing facilities on Cape Canaveral Space Force Station for recovering components of SpaceX's VTVL reusable launch vehicles. LZ-1 and LZ-2 were built on land leased in February 2015, on the site of the former Cape Canaveral Launch Complex 13. SpaceX built Landing Zone 2 at the facility to have a second landing pad, allowing two Falcon Heavy boosters to land simultaneously.

While the Starship program had only a small development team during the early years and a larger development and build team since late 2018, SpaceX CEO Elon Musk made Starship the top SpaceX development priority following the first human spaceflight launch of Crew Dragon in May 2020, except for anything related to reduction of crew return risk.

Starship is a family of reusable launch vehicles currently being developed by American private aerospace company SpaceX. It consists of a first stage named Super Heavy and a second stage named Starship. The stainless steel rocket consumes liquid oxygen and liquid methane for propulsion and moves its flaps for descent control. Starship can stack, launch and recover its stages via its launch pads and towers. During liftoff, 33 Raptor engines mounted under Super Heavy produce 72 meganewtons (16,000,000 lbf) of thrust, twice that of a Saturn V rocket. A Starship can launch more than 100 metric tons (220,000 lb) of payload to low Earth orbit, and place it to higher Earth orbits, the Moon, and Mars after being refueled by tanker Starships.

Raptor is a family of full-flow staged-combustion-cycle rocket engines developed and manufactured by SpaceX for use on the in-development SpaceX Starship. The engine is powered by cryogenic liquid methane and liquid oxygen (LOX), called methalox, rather than the RP-1 kerosene and LOX, called kerolox, used in SpaceX's prior Merlin and Kestrel rocket engines. The Raptor engine has more than twice the thrust of SpaceX's Merlin engine that powers their Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launch vehicles.

Boca Chica is an area on the eastern portion of a subdelta peninsula of Cameron County, at the far south of the US State of Texas along the Gulf Coast. It is bordered by the Brownsville Ship Channel to the north, the Rio Grande River and Mexico to the south, and the Gulf of Mexico to the east. The area extends approximately 25 miles (40 km) east of the city of Brownsville. The peninsula is served by Texas State Highway 4—also known as the Boca Chica Highway, or Boca Chica Boulevard within Brownsville city limits—which runs east-west, terminating at the Gulf and Boca Chica Beach.