This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations .(January 2019) |

The Treaty of Fort Meigs, also called the Treaty of the Maumee Rapids, formally titled, "Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., 1817", was the most significant Indian treaty by the United States in Ohio since the Treaty of Greenville in 1795. It resulted in cession by bands of several tribes of nearly all their remaining Indian lands in northwestern Ohio. It was the largest wholesale purchase by the United States of Indian land in the Ohio area. It was also the penultimate one; a small area below the St. Mary's River and north of the Greenville Treaty Line was ceded in the Treaty of St. Mary's in 1818.

Contents

The Treaty was signed September 29, 1817 at Fort Meigs between those chiefs and warriors of the Wyandot, Seneca, Delaware, Shawnee, Potawatomi, Ottawa and Chippewa (also known as the Ojibwe) tribes of Native Americans and official representatives of the United States of America: Lewis Cass, governor of Michigan Territory, and Gen. Duncan McArthur of Ohio. These historic tribes spoke a variety of distinct Iroquoian and Algonquian languages. The tribes were highly decentralized; others of their members lived in other regions around the Great Lakes.

The accord contained twenty-one articles and an addendum specifying land cession, allocation of Indian reservations and individual land grants, cash compensation to be paid by the United States, and acceptance of the terms by the various tribes.

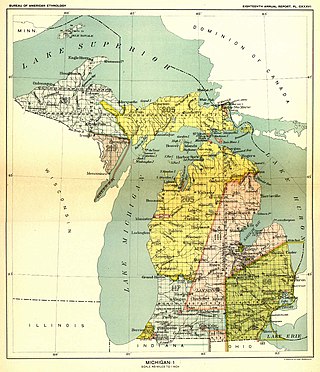

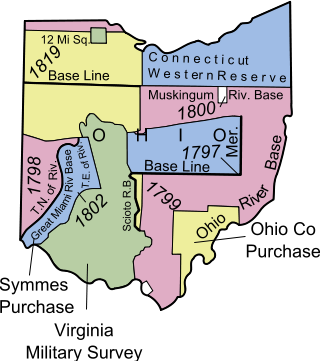

In this treaty the affiliated tribes relinquished their claim to 4.6 million acres of land in northwestern Ohio (almost 1/6 of the land area of the state), and chunks of northeastern Indiana and southern Michigan as well. The area was bounded by the Fort Industry Treaty Line in the East and the Greenville Treaty Line in the south; the western boundary angled northerly from the northwest corner of the Greenville Line (skipping around a small reservation near Loramie's store) to Kekionga, then zigzagged awkwardly northwest to Lake Erie, clipping off a chunk of southeastern Michigan; the northeastern boundary was Lake Erie. In a figurative way, the land cession was the inverse of that in the pre-Greenville Treaty of Fort McIntosh: in the Fort McIntosh Treaty, the circumscribed area, which included most of northwestern and central northern Ohio, was land reserved to the Indians; in the Fort Meigs Treaty, the circumscribed area, which included most of northwestern Ohio, is land ceded to the United States. After the treaty, with the exception of some tiny Indian reservations, Ohio was owned border to border by a United States dominated by European Americans (commonly referred to as whites). The border between ancestral Indian lands to the northwest and United States lands dominated by European Americans to the south and east shifted to Indiana. There the frontier was defined by the Treaty of Fort Wayne (1809).

The treaty of Fort Meigs reserved: for the Wyandot 12 miles square in Upper Sandusky around Fort Ferree; for the Seneca, thirty thousand acres on the Sandusky River near Wolf Creek; for the Shawnee, 10 miles square around Wapakoneta, also for the Shawnee, 25 square miles around Wapakoneta, also for the Shawnee, 48 square miles near of the headwaters of the Little Miami and Scioto Rivers. The Ottawa were granted use but not occupancy as reservations of two tracts, one 5 miles square on the Great Auglaize River and one 3 miles square on the Little Auglaize River. The Delaware, who occupied territory south of the Wabash River; the Chippewa or Ojibwe, who had migrated from northern Wisconsin and Minnesota; and the Potawatomi from the upper Mississippi Valley, were not allocated any reservations in Ohio.

In compensation, the United States agreed to pay annuities of various amounts for different lengths of time to the different tribes depending on their relative occupancy of the land. In addition, some tribes were paid cash amounts for damages they suffered as a result of allying with the United States against Great Britain in the War of 1812.

The treaty introduced the practice of making grants of land to individual Indians and sometimes to European Americans to encourage them to settle and farm the land. But these Indians were nomadic. As the resettlement and assimilation scheme to reservations failed, the government bought back the lands of the reservations, and resold them to whites. This resulted in speculation and fraud.

The Treaty was signed five days after the laying of the cornerstone for the fledgling University of Michigan campus in Detroit. Among the treaty's provisions was the ceding of 1,920 acres (7.8 km2) of land by the Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi tribes to the "college at Detroit" for either use or sale, and an equal amount to St. Anne's Catholic Church in Detroit, where Father Gabriel Richard was rector. French-Canadian settlers had established this church well before the territory became part of the US.

No college had officially been created yet by the Michigan territorial legislature, so the next month Reverend John Monteith and Father Richard decreed the creation of the " Catholepistemiad [2] of Michigania" at Detroit. It was renamed as the University of Michigan in 1821. It moved to a new campus developed in Ann Arbor, Michigan in 1837.