The Hopewell tradition, also called the Hopewell culture and Hopewellian exchange, describes a network of precontact Native American cultures that flourished in settlements along rivers in the northeastern and midwestern Eastern Woodlands from 100 BCE to 500 CE, in the Middle Woodland period. The Hopewell tradition was not a single culture or society but a widely dispersed set of populations connected by a common network of trade routes.

The Great Serpent Mound is a 1,348-feet-long (411 m), three-feet-high prehistoric effigy mound located in Peebles, Ohio. It was built on what is known as the Serpent Mound crater plateau, running along the Ohio Brush Creek in Adams County, Ohio. The mound is the largest serpent effigy known in the world.

The Fort Ancient culture is a Native American archaeological culture that dates back to c. 1000–1750 CE. Members of the culture lived along the Ohio River valley, in an area running from modern-day Ohio and western West Virginia through to northern Kentucky and parts of southeastern Indiana. A contemporary of the neighboring Mississippian culture, Fort Ancient is considered to be a separate "sister culture". Mitochondrial DNA evidence collected from the area suggests that the Fort Ancient culture did not directly descend from the older Hopewell Culture.

Many pre-Columbian cultures in North America were collectively termed "Mound Builders", but the term has no formal meaning. It does not refer to specific people or archaeological culture but refers to the characteristic mound earthworks that indigenous peoples erected for an extended period of more than 5,000 years. The "Mound Builder" cultures span the period of roughly 3500 BCE to the 16th century CE, including the Archaic period, Woodland period, and Mississippian period. Geographically, the cultures were present in the region of the Great Lakes, the Ohio River Valley, Florida, and the Mississippi River Valley and its tributary waters.

Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, Southeastern cultures, or Southeast Indians are an ethnographic classification for Native Americans who have traditionally inhabited the area now part of the Southeastern United States and the northeastern border of Mexico, that share common cultural traits. This classification is a part of the Eastern Woodlands. The concept of a southeastern cultural region was developed by anthropologists, beginning with Otis Mason and Franz Boas in 1887. The boundaries of the region are defined more by shared cultural traits than by geographic distinctions. Because the cultures gradually instead of abruptly shift into Plains, Prairie, or Northeastern Woodlands cultures, scholars do not always agree on the exact limits of the Southeastern Woodland culture region. Shawnee, Powhatan, Waco, Tawakoni, Tonkawa, Karankawa, Quapaw, and Mosopelea are usually seen as marginally southeastern and their traditional lands represent the borders of the cultural region.

This is a timeline of in North American prehistory, from 1000 BC until European contact.

The Kincaid Mounds Historic Site c. 1050–1400 CE, is a Mississippian culture archaeological site located at the southern tip of present-day U.S. state of Illinois, along the Ohio River. Kincaid Mounds has been notable for both its significant role in native North American prehistory and for the central role the site has played in the development of modern archaeological techniques. The site had at least 11 substructure platform mounds, and 8 other monuments.

Albany Mounds State Historic Site, also known as Albany Mounds Site, is a historic site operated by the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency. It spans over 205 acres of land near the Mississippi River at the northwest edge of the state of Illinois in the United States. In 1974, the site was added to the National Register of Historic Places list. The historical site is under the provision of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, a governmental agency founded in 1985 for the maintaining of historical sites within the state. In the 1990s, the site underwent a restoration project that aimed to return its appearance to its original condition.

The Prehistory of West Virginia spans ancient times until the arrival of Europeans in the early 17th century. Hunters ventured into West Virginia's mountain valleys and made temporary camp villages since the Archaic period in the Americas. Many ancient human-made earthen mounds from various mound builder cultures survive, especially in the areas of Moundsville, South Charleston, and Romney. The artifacts uncovered in these areas give evidence of a village society with a tribal trade system culture that included limited cold worked copper. As of 2009, over 12,500 archaeological sites have been documented in West Virginia.

The archaeology of Iowa is the study of the buried remains of human culture within the U.S. state of Iowa from the earliest prehistoric through the late historic periods. When the American Indians first arrived in what is now Iowa more than 13,000 years ago, they were hunters and gatherers living in a Pleistocene glacial landscape. By the time European explorers visited Iowa, American Indians were largely settled farmers with complex economic, social, and political systems. This transformation happened gradually. During the Archaic period American Indians adapted to local environments and ecosystems, slowly becoming more sedentary as populations increased. More than 3,000 years ago, during the Late Archaic period, American Indians in Iowa began utilizing domesticated plants. The subsequent Woodland period saw an increase on the reliance on agriculture and social complexity, with increased use of mounds, ceramics, and specialized subsistence. During the Late Prehistoric period increased use of maize and social changes led to social flourishing and nucleated settlements. The arrival of European trade goods and diseases in the Protohistoric period led to dramatic population shifts and economic and social upheaval, with the arrival of new tribes and early European explorers and traders. During the Historical period European traders and American Indians in Iowa gave way to American settlers and Iowa was transformed into an agricultural state.

The Pisgah phase is an archaeological phase of the South Appalachian Mississippian culture in Southeast North America. It is associated with the Appalachian Summit area of southeastern Tennessee, Western North Carolina, and northwestern South Carolina in what is now the United States.

The Oak Mounds is a large prehistoric earthwork mound, and a smaller mound to the west. They are located outside Clarksburg, in Harrison County, West Virginia. These mounds have never been totally excavated but they were probably built between 1 and 1000 CE by the Hopewell culture mound builders, prehistoric indigenous peoples of eastern North America. The larger mound is about 12 feet high and 60 feet in diameter. A number of burials of important persons of the culture probably occurred in these mounds.

The Point Peninsula complex was an indigenous culture located in Ontario and New York from 600 BCE to 700 CE. Point Peninsula ceramics were first introduced into Canada around 600 BCE then spread south into parts of New England around 200 BCE. Some time between 300 BCE and 1 CE, Point Peninsula pottery first appeared in Maine, and "over the entire Maritime Peninsula." Little evidence exists to show that it was derived from the earlier, thicker pottery, known as Vinette I, Adena Thick, etc... Point Peninsula pottery represented a new kind of technology in North America and has also been called Vinette II. Compared to existing ceramics that were thicker and less decorated, this new pottery has been characterized by "superior modeling of the clay with vessels being thinner, better fired and containing finer grit temper." Where this new pottery technology originated is not known for sure. The origin of this pottery is "somewhat of a problem." The people are thought to have been influenced by the Hopewell traditions of the Ohio River valley. This influence seems to have ended about 250 CE, after which they no longer practiced burial ceremonialism.

The Laurel complex or Laurel tradition is an archaeological culture which was present in what is now southern Quebec, southern and northwestern Ontario and east-central Manitoba in Canada, and northern Michigan, northwestern Wisconsin and northern Minnesota in the United States. They were the first pottery using people of Ontario north of the Trent–Severn Waterway. The complex is named after the former unincorporated community of Laurel, Minnesota. It was first defined by Lloyd Wilford in 1941.

The Kansas City Hopewell were the farthest west regional variation of the Hopewell tradition of the Middle Woodland period. Sites were located in Kansas and Missouri around the mouth of the Kansas River where it enters the Missouri River. There are 30 recorded Kansas City Hopewell sites.

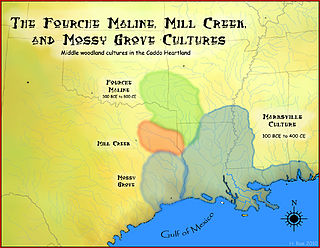

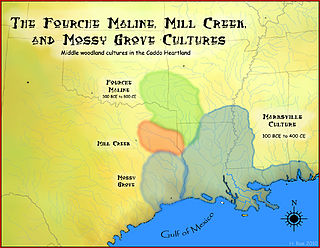

The Marksville culture was an archaeological culture in the lower Lower Mississippi valley, Yazoo valley, and Tensas valley areas of present-day Louisiana, Mississippi, Arkansas, and extended eastward along the Gulf Coast to the Mobile Bay area, from 100 BCE to 400 CE. This culture takes its name from the Marksville Prehistoric Indian Site in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana. Marksville Culture was contemporaneous with the Hopewell cultures within present-day Ohio and Illinois. It evolved from the earlier Tchefuncte culture and into the Baytown and Troyville cultures, and later the Coles Creek and Plum Bayou cultures. It is considered ancestral to the historic Natchez and Taensa peoples.

The Fourche Maline culture was a Woodland Period Native American culture that existed from 300 BCE to 800 CE, in what are now defined as southeastern Oklahoma, southwestern Arkansas, northwestern Louisiana, and northeastern Texas. They are considered to be one of the main ancestral groups of the Caddoan Mississippian culture, along with the contemporaneous Mill Creek culture of eastern Texas. This culture was named for the Fourche Maline Creek, a tributary of the Poteau River. Their modern descendants are the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma.

The Moccasin Bluff site is an archaeological site located along the Red Bud Trail and the St. Joseph River north of Buchanan, Michigan. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1977, and has been classified as a multi-component prehistoric site with the major component dating to the Late Woodland/Upper Mississippian period.

The Yellow Bluffs archeological site was occupied by people of the Middle Woodland Havana Tradition and consists of a habitation area and various burial mounds. The primary occupation of the Yellow Bluffs site, be it continuous or discrete, can be traced back to 200 B.C.E through 400 C.E. but the site represents activity from numerous prehistoric eras. The archaeological site can be found in Logan County, central Illinois and is closely linked to the Sangamon River drainage network. It is one of the larger known sites in the Sangamon River valley.