In mathematics and computer science, mutual recursion is a form of recursion where two mathematical or computational objects, such as functions or datatypes, are defined in terms of each other. Mutual recursion is very common in functional programming and in some problem domains, such as recursive descent parsers, where the datatypes are naturally mutually recursive.

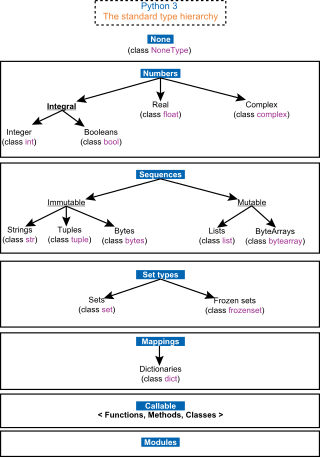

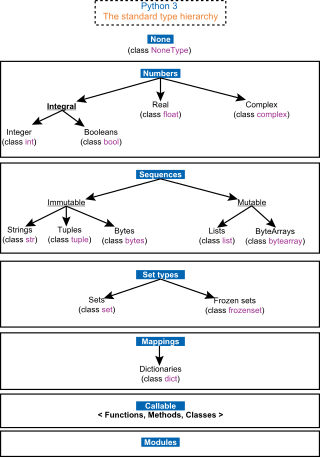

In computer science and computer programming, a data type is a collection or grouping of data values, usually specified by a set of possible values, a set of allowed operations on these values, and/or a representation of these values as machine types. A data type specification in a program constrains the possible values that an expression, such as a variable or a function call, might take. On literal data, it tells the compiler or interpreter how the programmer intends to use the data. Most programming languages support basic data types of integer numbers, floating-point numbers, characters and Booleans.

Standard ML (SML) is a general-purpose, high-level, modular, functional programming language with compile-time type checking and type inference. It is popular for writing compilers, for programming language research, and for developing theorem provers.

In computer science, pattern matching is the act of checking a given sequence of tokens for the presence of the constituents of some pattern. In contrast to pattern recognition, the match usually has to be exact: "either it will or will not be a match." The patterns generally have the form of either sequences or tree structures. Uses of pattern matching include outputting the locations of a pattern within a token sequence, to output some component of the matched pattern, and to substitute the matching pattern with some other token sequence.

In computer science, a tagged union, also called a variant, variant record, choice type, discriminated union, disjoint union, sum type, or coproduct, is a data structure used to hold a value that could take on several different, but fixed, types. Only one of the types can be in use at any one time, and a tag field explicitly indicates which type is in use. It can be thought of as a type that has several "cases", each of which should be handled correctly when that type is manipulated. This is critical in defining recursive datatypes, in which some component of a value may have the same type as that value, for example in defining a type for representing trees, where it is necessary to distinguish multi-node subtrees and leaves. Like ordinary unions, tagged unions can save storage by overlapping storage areas for each type, since only one is in use at a time.

In computer science, tree traversal is a form of graph traversal and refers to the process of visiting each node in a tree data structure, exactly once. Such traversals are classified by the order in which the nodes are visited. The following algorithms are described for a binary tree, but they may be generalized to other trees as well.

In computer science, a parsing expression grammar (PEG) is a type of analytic formal grammar, i.e. it describes a formal language in terms of a set of rules for recognizing strings in the language. The formalism was introduced by Bryan Ford in 2004 and is closely related to the family of top-down parsing languages introduced in the early 1970s. Syntactically, PEGs also look similar to context-free grammars (CFGs), but they have a different interpretation: the choice operator selects the first match in PEG, while it is ambiguous in CFG. This is closer to how string recognition tends to be done in practice, e.g. by a recursive descent parser.

In computer science, corecursion is a type of operation that is dual to recursion. Whereas recursion works analytically, starting on data further from a base case and breaking it down into smaller data and repeating until one reaches a base case, corecursion works synthetically, starting from a base case and building it up, iteratively producing data further removed from a base case. Put simply, corecursive algorithms use the data that they themselves produce, bit by bit, as they become available, and needed, to produce further bits of data. A similar but distinct concept is generative recursion, which may lack a definite "direction" inherent in corecursion and recursion.

In computer programming languages, a recursive data type is a data type for values that may contain other values of the same type. Data of recursive types are usually viewed as directed graphs.

In computer science, recursion is a method of solving a computational problem where the solution depends on solutions to smaller instances of the same problem. Recursion solves such recursive problems by using functions that call themselves from within their own code. The approach can be applied to many types of problems, and recursion is one of the central ideas of computer science.

The power of recursion evidently lies in the possibility of defining an infinite set of objects by a finite statement. In the same manner, an infinite number of computations can be described by a finite recursive program, even if this program contains no explicit repetitions.

In functional programming, the concept of catamorphism denotes the unique homomorphism from an initial algebra into some other algebra.

In many programming languages, map is a higher-order function that applies a given function to each element of a collection, e.g. a list or set, returning the results in a collection of the same type. It is often called apply-to-all when considered in functional form.

In functional programming, fold refers to a family of higher-order functions that analyze a recursive data structure and through use of a given combining operation, recombine the results of recursively processing its constituent parts, building up a return value. Typically, a fold is presented with a combining function, a top node of a data structure, and possibly some default values to be used under certain conditions. The fold then proceeds to combine elements of the data structure's hierarchy, using the function in a systematic way.

In functional programming, a generalized algebraic data type is a generalization of a parametric algebraic data type (ADT).

In computer programming, an anamorphism is a function that generates a sequence by repeated application of the function to its previous result. You begin with some value A and apply a function f to it to get B. Then you apply f to B to get C, and so on until some terminating condition is reached. The anamorphism is the function that generates the list of A, B, C, etc. You can think of the anamorphism as unfolding the initial value into a sequence.

A zipper is a technique of representing an aggregate data structure so that it is convenient for writing programs that traverse the structure arbitrarily and update its contents, especially in purely functional programming languages. The zipper was described by Gérard Huet in 1997. It includes and generalizes the gap buffer technique sometimes used with arrays.

In computing, a rose tree is a term for the value of a tree data structure with a variable and unbounded number of branches per node. The term is mostly used in the functional programming community, e.g., in the context of the Bird–Meertens formalism. Apart from the multi-branching property, the most essential characteristic of rose trees is the coincidence of bisimilarity with identity: two distinct rose trees are never bisimilar.

In computer science, and in particular functional programming, a hylomorphism is a recursive function, corresponding to the composition of an anamorphism followed by a catamorphism. Fusion of these two recursive computations into a single recursive pattern then avoids building the intermediate data structure. This is an example of deforestation, a program optimization strategy. A related type of function is a metamorphism, which is a catamorphism followed by an anamorphism.

In computer science, polymorphic recursion refers to a recursive parametrically polymorphic function where the type parameter changes with each recursive invocation made, instead of staying constant. Type inference for polymorphic recursion is equivalent to semi-unification and therefore undecidable and requires the use of a semi-algorithm or programmer-supplied type annotations.

In mathematical logic, a term denotes a mathematical object while a formula denotes a mathematical fact. In particular, terms appear as components of a formula. This is analogous to natural language, where a noun phrase refers to an object and a whole sentence refers to a fact.