The Indian Ocean brown cloud or Asian brown cloud is a layer of air pollution that recurrently covers parts of South Asia, namely the northern Indian Ocean, India, and Pakistan. [1] [2] Viewed from satellite photos, the cloud appears as a giant brown stain hanging in the air over much of the Indian subcontinent and the Indian Ocean every year between October and February, possibly also during earlier and later months. The term was coined in reports from the UNEP Indian Ocean Experiment (INDOEX). It was found to originate mostly due to farmers burning stubble in northern Indian states such as Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh, as well as in the Punjab region of Pakistan. The debilitating air quality in Delhi is also due to the stubble burning in Punjab. [3]

The term atmospheric brown cloud is used for a more generic context not specific to the Asian region. [4]

The Asian brown cloud is created by a range of airborne particles and pollutants from combustion (e.g., woodfires, cars, and factories), biomass burning [5] and industrial processes with incomplete burning. [6] The cloud is associated with the winter monsoon (October/November to February/March) during which there is no rain to wash pollutants from the air. [7]

This pollution layer was observed during the Indian Ocean Experiment (INDOEX) intensive field observation in 1999 and described in the UNEP impact assessment study published 2002. [3] Scientists in India claimed that the Asian Brown cloud is not something specific to Asia. [8] Subsequently, when the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) organized a follow-up international project, the subject of study was renamed the Atmospheric Brown Cloud with focus on Asia.

The cloud was also reported by NASA in 2004 [9] and 2007. [10]

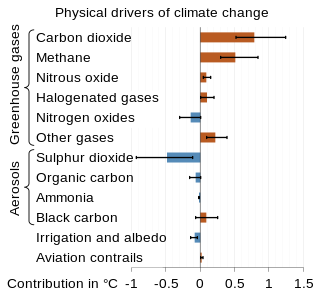

Although aerosol particles are generally associated with a global cooling effect, recent studies have shown that they can actually have a global warming effect in certain regions such as the Himalayas. [11]

One major impact is on health. A 2002 study indicated nearly two million people die each year, in Asia alone, from conditions related to the brown cloud. [12]

A second assessment study was published in 2008. [13] It highlighted regional concerns regarding:

A 2011 study found that pollution is making Arabian Sea cyclones more intense as the atmospheric brown clouds has been producing weakening wind patterns which prevent wind shear patterns that historically have prohibited cyclones in the Arabian Sea from becoming major storms. This phenomenon was found responsible for the formation of stronger storms in 2007 and 2010 that were the first recorded storms to enter the Gulf of Oman. [17] [18]

The 2008 report also addressed the global concern of warming and concluded that the brown clouds have masked 20 to 80 percent of greenhouse gas forcing in the past century. The report suggested that air pollution regulations can have large amplifying effects on global warming.[ clarification needed ]

Another major impact is on the polar ice caps. Black carbon (soot) in the Asian Brown Cloud may be reflecting sunlight and dimming Earth below but it is warming other places by absorbing incoming radiation and warming the atmosphere and whatever it touches. [19] Black carbon is three times more effective than carbon dioxide—the most common greenhouse gas—at melting polar ice and snow. [20] Black carbon in snow causes about three times the temperature change as carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. On snow—even at concentrations below five parts per billion–dark carbon triggers melting, and may be responsible for as much as 94 percent of Arctic warming. [21]

The scientific community has been investigating the causes of climate change for decades. After thousands of studies, it came to a consensus, where it is "unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land since pre-industrial times." This consensus is supported by around 200 scientific organizations worldwide, The dominant role in this climate change has been played by the direct emissions of carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels. Indirect CO2 emissions from land use change, and the emissions of methane, nitrous oxide and other greenhouse gases play major supporting roles.

Cloud feedback is a type of climate change feedback, where the overall cloud frequency, height, and the relative fraction of the different types of clouds are altered due to climate change, and these changes then affect the Earth's energy balance. On their own, clouds are already an important part of the climate system, as they consist of water vapor, which acts as a greenhouse gas and so contributes to warming; at the same time, they are bright and reflective of the Sun, which causes cooling. Clouds at low altitudes have a stronger cooling effect, and those at high altitudes have a stronger warming effect. Altogether, clouds make the Earth cooler than it would have been without them.

An anticyclone is a weather phenomenon defined as a large-scale circulation of winds around a central region of high atmospheric pressure, clockwise in the Northern Hemisphere and counterclockwise in the Southern Hemisphere as viewed from above. Effects of surface-based anticyclones include clearing skies as well as cooler, drier air. Fog can also form overnight within a region of higher pressure.

Global cooling was a conjecture, especially during the 1970s, of imminent cooling of the Earth culminating in a period of extensive glaciation, due to the cooling effects of aerosols or orbital forcing. Some press reports in the 1970s speculated about continued cooling; these did not accurately reflect the scientific literature of the time, which was generally more concerned with warming from an enhanced greenhouse effect.

Global dimming is a decline in the amount of sunlight reaching the Earth's surface. It is caused by atmospheric particulate matter, predominantly sulfate aerosols, which are components of air pollution. Global dimming was observed soon after the first systematic measurements of solar irradiance began in the 1950s. This weakening of visible sunlight proceeded at the rate of 4–5% per decade until the 1980s. During these years, air pollution increased due to post-war industrialization. Solar activity did not vary more than the usual during this period.

James Edward Hansen is an American adjunct professor directing the Program on Climate Science, Awareness and Solutions of the Earth Institute at Columbia University. He is best known for his research in climatology, his 1988 Congressional testimony on climate change that helped raise broad awareness of global warming, and his advocacy of action to avoid dangerous climate change. In recent years, he has become a climate activist to mitigate the effects of global warming, on a few occasions leading to his arrest.

Black carbon (BC) is the light-absorbing refractory form of elemental carbon remaining after pyrolysis or produced by incomplete combustion.

Earth's climate system is a complex system with five interacting components: the atmosphere (air), the hydrosphere (water), the cryosphere, the lithosphere and the biosphere. Climate is the statistical characterization of the climate system. It represents the average weather, typically over a period of 30 years, and is determined by a combination of processes, such as ocean currents and wind patterns. Circulation in the atmosphere and oceans transports heat from the tropical regions to regions that receive less energy from the Sun. Solar radiation is the main driving force for this circulation. The water cycle also moves energy throughout the climate system. In addition, certain chemical elements are constantly moving between the components of the climate system. Two examples for these biochemical cycles are the carbon and nitrogen cycles.

Arctic haze is the phenomenon of a visible reddish-brown springtime haze in the atmosphere at high latitudes in the Arctic due to anthropogenic air pollution. A major distinguishing factor of Arctic haze is the ability of its chemical ingredients to persist in the atmosphere for significantly longer than other pollutants. Due to limited amounts of snow, rain, or turbulent air to displace pollutants from the polar air mass in spring, Arctic haze can linger for more than a month in the northern atmosphere.

The chemical equator term and concept was coined in 2008 when researchers from University of York discovered a distinct divide between the polluted air and haze over Indonesia from the largely uncontaminated atmosphere over Australia. This divide is distinguishable by a rapid increase in atmospheric levels of carbon monoxide and other pollutants from the Tropical Warm Pool region northward. The divide of the atmosphere of the northern hemisphere from the atmosphere of the southern hemisphere is different from that of the Intertropical Convergence Zone.

Veerabhadran "Ram" Ramanathan is Edward A. Frieman Endowed Presidential Chair in Climate Sustainability Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of California, San Diego. He has contributed to many areas of the atmospheric and climate sciences including developments to general circulation models, atmospheric chemistry, and radiative transfer. He has been a part of major projects such as the Indian Ocean Experiment (INDOEX) and the Earth Radiation Budget Experiment (ERBE), and is known for his contributions to the areas of climate physics, Climate Change and atmospheric aerosols research. He is now the Chair of Bending the Curve: Climate Change Solutions education project of University of California. He has received numerous awards, and is a member of the US National Academy of Sciences. He has spoken about the topic of global warming, and written that "the effect of greenhouse gases on global warming is, in my opinion, the most important environmental issue facing the world today."

Stratospheric aerosol injection (SAI) is a proposed method of solar geoengineering to reduce global warming. This would introduce aerosols into the stratosphere to create a cooling effect via global dimming and increased albedo, which occurs naturally from volcanic winter. It appears that stratospheric aerosol injection, at a moderate intensity, could counter most changes to temperature and precipitation, take effect rapidly, have low direct implementation costs, and be reversible in its direct climatic effects. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concludes that it "is the most-researched [solar geoengineering] method that it could limit warming to below 1.5 °C (2.7 °F)." However, like other solar geoengineering approaches, stratospheric aerosol injection would do so imperfectly and other effects are possible, particularly if used in a suboptimal manner.

The history of the scientific discovery of climate change began in the early 19th century when ice ages and other natural changes in paleoclimate were first suspected and the natural greenhouse effect was first identified. In the late 19th century, scientists first argued that human emissions of greenhouse gases could change Earth's energy balance and climate. The existence of the greenhouse effect, while not named as such, was proposed as early as 1824 by Joseph Fourier. The argument and the evidence were further strengthened by Claude Pouillet in 1827 and 1838. In 1856 Eunice Newton Foote demonstrated that the warming effect of the sun is greater for air with water vapour than for dry air, and the effect is even greater with carbon dioxide.

Tectonic–climatic interaction is the interrelationship between tectonic processes and the climate system. The tectonic processes in question include orogenesis, volcanism, and erosion, while relevant climatic processes include atmospheric circulation, orographic lift, monsoon circulation and the rain shadow effect. As the geological record of past climate changes over millions of years is sparse and poorly resolved, many questions remain unresolved regarding the nature of tectonic-climate interaction, although it is an area of active research by geologists and palaeoclimatologists.

The Climate and Clean Air Coalition to Reduce Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (CCAC) was launched by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and six countries—Bangladesh, Canada, Ghana, Mexico, Sweden, and the United States—on 16 February 2012. The CCAC aims to catalyze rapid reductions in short-lived climate pollutants to protect human health, agriculture and the environment. To date, more than $90 million has been pledged to the Climate and Clean Air Coalition from Canada, Denmark, the European Commission, Germany, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and the United States. The program is managed out of the United Nations Environmental Programme through a Secretariat in Paris, France.

The Indian Ocean Experiment (INDOEX) was a 1999 multinational scientific study designed to measure the transport of air pollution from Southeast Asia into the Indian Ocean. The project was led by Veerabhadran Ramanathan.

Sreedharan Krishnakumari Satheesh is an Indian meteorologist and a professor at the Centre for Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences of the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). He holds the chair of the Divecha Centre for Climate Change, a centre under the umbrella of the IISc for researches on climate variability, climate change and their impact on the environment. He is known for his studies on atmospheric aerosols and is an elected fellow of all the three major Indian science academies viz. Indian Academy of Sciences Indian National Science Academy and the National Academy of Sciences, India as well as The World Academy of Sciences. The Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, the apex agency of the Government of India for scientific research, awarded him the Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar Prize for Science and Technology, one of the highest Indian science awards for his contributions to Earth, Atmosphere, Ocean and Planetary Sciences in 2009. He received the TWAS Prize of The World Academy of Sciences in 2011. In 2018, he received the Infosys Prize, one of the highest monetary awards in India that recognize excellence in science and research, for his work in the field of climate change.

The Dr. Neil Trivett Global Atmosphere Watch Observatory is an atmospheric baseline station operated by Environment and Climate Change Canada located about 6 km (3.7 mi) south south-west of Alert, Nunavut, on the north-eastern tip of Ellesmere Island, about 800 km (500 mi) south of the geographic North Pole.

Heavy fuel oil (HFO) is a category of fuel oils of a tar-like consistency. Also known as bunker fuel, or residual fuel oil, HFO is the result or remnant from the distillation and cracking process of petroleum. For this reason, HFO is contaminated with several different compounds including aromatics, sulfur, and nitrogen, making emissions upon combustion more polluting compared to other fuel oils. HFO is predominantly used as a fuel source for marine vessel propulsion using marine diesel engines due to its relatively low cost compared to cleaner fuel sources such as distillates. The use and carriage of HFO on-board vessels presents several environmental concerns, namely the risk of oil spill and the emission of toxic compounds and particulates including black carbon. The use of HFOs is banned as a fuel source for ships travelling in the Antarctic as part of the International Maritime Organization's (IMO) International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters (Polar Code). For similar reasons, an HFO ban in Arctic waters is currently being considered.

Johannes "Jos" Lelieveld is a Dutch atmospheric chemist. Since 2000, he has been a Scientific Member of the Max Planck Society and director of the Atmospheric Chemistry Department at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry in Mainz. He is also professor at the University of Mainz and at the Cyprus Institute in Nicosia.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)