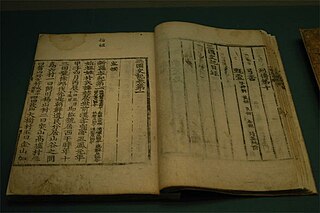

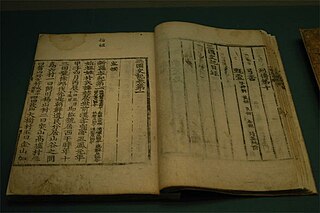

Samguk sagi is a historical record of the Three Kingdoms of Korea: Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla. Completed in 1145, it is well-known in Korea as the oldest surviving chronicle of Korean history.

Muryeong was the 25th king of Baekje, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. During his reign, Baekje remained allied with Silla against Goguryeo, and expanded its relationships with China and Japan.

Baekje or Paekche was a Korean kingdom located in southwestern Korea from 18 BCE to 660 CE. It was one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, together with Goguryeo and Silla. While the three kingdoms were in separate existence, Baekje had the highest population of approximately 3,800,000 people, which was much larger than that of Silla and similar to that of Goguryeo.

Gaya was a Korean confederacy of territorial polities in the Nakdong River basin of southern Korea, growing out of the Byeonhan confederacy of the Samhan period.

The Peninsular Japonic languages are now-extinct Japonic languages reflected in ancient placenames and glosses from central and southern parts of the Korean Peninsula. Most linguists believe that Japonic arrived in the Japanese archipelago from the Korean peninsula during the first millennium BCE. The placename evidence suggests that Japonic languages were still spoken in parts of the peninsula for several centuries before being replaced by the spread of Korean.

The Goguryeo language, or Koguryoan, was the language of the ancient kingdom of Goguryeo, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. Early Chinese histories state that the language was similar to those of Buyeo, Okjeo and Ye. Lee Ki-Moon grouped these four as the Puyŏ languages. The histories also stated that these languages were different from those of the Yilou and Mohe. All of these languages are unattested except for Goguryeo, for which evidence is limited and controversial.

Jinhan was a loose confederacy of chiefdoms that existed from around the 1st century BC to the 4th century AD in the southern Korean Peninsula, to the east of the Nakdong River valley, Gyeongsang Province. Jinhan was one of the Samhan, along with Byeonhan and Mahan. Apparently descending from the Jin state of southern Korea, Jinhan was absorbed by the later Silla, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.

The state of Jin was a confederacy of statelets which occupied some portion of the southern Korean peninsula from the 4th to 2nd centuries BCE, bordering the Korean Kingdom of Gojoseon to the north. Its capital was somewhere south of the Han River. It preceded the Samhan confederacies, each of which claimed to be the successor of the Jin state.

Samhan, or Three Han, is the collective name of the Byeonhan, Jinhan, and Mahan confederacies that emerged in the first century BC during the Proto–Three Kingdoms of Korea, or Samhan, period. Located in the central and southern regions of the Korean Peninsula, the Samhan confederacies eventually merged and developed into the Baekje, Gaya, and Silla kingdoms. The name "Samhan" also refers to the Three Kingdoms of Korea.

Korea's military history spans thousands of years, beginning with the ancient nation of Gojoseon and continuing into the present day with the countries of North Korea and South Korea, and is notable for its many successful triumphs over invaders.

Very little is known of the language of the Buyeo kingdom. Chapter 30 "Description of the Eastern Barbarians" in the Records of the Three Kingdoms records a survey carried out by the Chinese state of Wei after their defeat of Goguryeo in 244. The report states that the languages of Buyeo and those of its southern neighbours Goguryeo and Ye were similar, and that the language of Okjeo was only slightly different from them. Based on this text, Lee Ki-Moon grouped the four languages as the Puyŏ languages, contemporaneous with the Han languages of the Samhan confederacies in southern Korea.

Old Korean is the first historically documented stage of the Korean language, typified by the language of the Unified Silla period (668–935).

The traditional periodization of Korean distinguishes:

Gaya, also rendered Kaya, Kara or Karak, is the presumed language of the Gaya confederacy in ancient southern Korea. Only one word survives that is directly identified as being from the language of Gaya. Other evidence consists of place names, whose interpretation is uncertain.

Koreanic is a small language family consisting of the Korean and Jeju languages. The latter is often described as a dialect of Korean but is distinct enough to be considered a separate language. Alexander Vovin suggested that the Yukjin dialect of the far northeast should be similarly distinguished. Korean has been richly documented since the introduction of the Hangul alphabet in the 15th century. Earlier renditions of Korean using Chinese characters are much more difficult to interpret.

The Puyŏ or Puyo-Koguryoic languages are four languages of northern Korea and eastern Manchuria mentioned in ancient Chinese sources. The languages of Buyeo, Goguryeo, Dongye and Okjeo were said to be similar to one another but different from the language of the Yilou to the north . Other sources suggest that the ruling class of Baekje may have spoken a Puyŏ language.

The Government of Baekje, was the court system of Baekje (百濟), one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea which lasted from 18 BCE–660 CE.

The Han languages or Samhan languages were the languages of the Samhan of ancient southern Korea, the confederacies of Mahan, Byeonhan and Jinhan. They are mentioned in surveys of the peninsula in the 3rd century found in Chinese histories, which also contain lists of placenames, but are otherwise unattested. There is no consensus about the relationships between these languages and the languages of later kingdoms.

Chapter 37 of the Samguk sagi contains a list of place names and their meanings, from part of central Korea captured by Silla from the former state of Goguryeo (Koguryŏ). Some of the vocabulary extracted from these names provides the principal evidence that Japonic languages were formerly spoken in central and southern parts of the Korean peninsula. Other words resemble Korean or Tungusic words.

Mahan is the presumed ancient language of the Mahan confederacy in southern Korea. This language is virtually unattested.