In grammar, the dative case is a grammatical case used in some languages to indicate the recipient or beneficiary of an action, as in "Maria Jacobo potum dedit", Latin for "Maria gave Jacob a drink". In this example, the dative marks what would be considered the indirect object of a verb in English.

A grammatical case is a category of nouns and noun modifiers that corresponds to one or more potential grammatical functions for a nominal group in a wording. In various languages, nominal groups consisting of a noun and its modifiers belong to one of a few such categories. For instance, in English, one says I see them and they see me: the nominative pronouns I/they represent the perceiver, and the accusative pronouns me/them represent the phenomenon perceived. Here, nominative and accusative are cases, that is, categories of pronouns corresponding to the functions they have in representation.

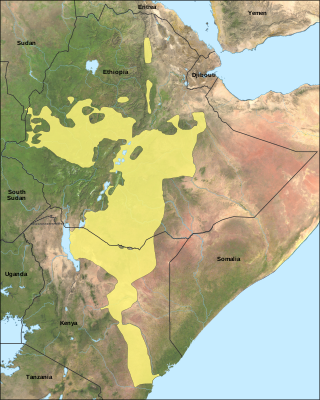

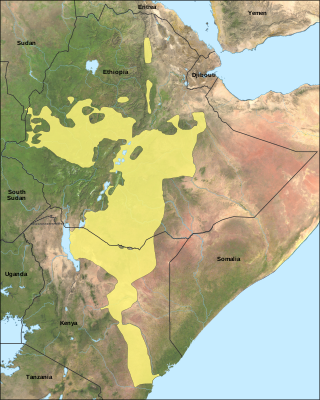

Oromo, historically also called Galla, which is regarded by the Oromo as pejorative, is an Afroasiatic language that belongs to the Cushitic branch. It is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia and northern Kenya and is spoken predominantly by the Oromo people and neighboring ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa. It is used as a lingua franca particularly in the Oromia Region and northeastern Kenya.

Aymara is an Aymaran language spoken by the Aymara people of the Bolivian Andes. It is one of only a handful of Native American languages with over one million speakers. Aymara, along with Spanish and Quechua, is an official language in Bolivia and Peru. It is also spoken, to a much lesser extent, by some communities in northern Chile, where it is a recognized minority language.

Russian grammar employs an Indo-European inflexional structure, with considerable adaptation.

Crimean Tatar, also called Crimean, is a Kipchak Turkic language spoken in Crimea and the Crimean Tatar diasporas of Uzbekistan, Turkey and Bulgaria, as well as small communities in the United States and Canada. It should not be confused with Tatar, spoken in Tatarstan and adjacent regions in Russia; the two languages are related, but belong to different subgroups of the Kipchak languages, while maintaining a significant degree of mutual intelligibility. Crimean Tatar has been extensively influenced by nearby Oghuz dialects and is also mutually intelligible with them to varying degrees.

A reflexive pronoun is a pronoun that refers to another noun or pronoun within the same sentence.

In linguistics, especially within generative grammar, phi features are the morphological expression of a semantic process in which a word or morpheme varies with the form of another word or phrase in the same sentence. This variation can include person, number, gender, and case, as encoded in pronominal agreement with nouns and pronouns. Several other features are included in the set of phi-features, such as the categorical features ±N (nominal) and ±V (verbal), which can be used to describe lexical categories and case features.

Personal pronouns are pronouns that are associated primarily with a particular grammatical person – first person, second person, or third person. Personal pronouns may also take different forms depending on number, grammatical or natural gender, case, and formality. The term "personal" is used here purely to signify the grammatical sense; personal pronouns are not limited to people and can also refer to animals and objects.

Hindustani, the lingua franca of Northern India and Pakistan, has two standardised registers: Hindi and Urdu. Grammatical differences between the two standards are minor but each uses its own script: Hindi uses Devanagari while Urdu uses an extended form of the Perso-Arabic script, typically in the Nastaʿlīq style.

Karitiana, otherwise known as Caritiana or Yjxa, is a Tupian language spoken in the State of Rondônia, Brazil, by 210 out of 320 Karitiana people, or 400 according to Cláudio Karitiana, in the Karitiana reserve 95 kilometres south of Porto Velho. The language belongs to the Arikém language family from the Tupi stock. It is the only surviving language in the family after the other two members, Kabixiâna and Arikém, became extinct.

Argentine Sign Language is used in Argentina. Deaf people attend separate schools, and use local sign languages out of class. A manual alphabet for spelling Spanish has been developed.

The Uwa language, Uw Cuwa, commonly known as Tunebo, is a Chibchan language spoken by between 1,800 and 3,600 of the Uwa people of Colombia, out of a total population of about 7,000.

The Hup language is one of the four Naduhup languages. It is spoken by the Hupda indigenous Amazonian peoples who live on the border between Colombia and the Brazilian state of Amazonas. There are approximately 1500 speakers of the Hup language. As of 2005, according to the linguist Epps, Hup is not seriously endangered – although the actual number of speakers is few, all Hupda children learn Hup as their first language.

This article deals with the grammar of the Udmurt language.

Colognian grammar describes the formal systems of the modern Colognian language or dialect cluster used in Cologne currently and during at least the past 150 years. It does not cover the Historic Colognian grammar, although similarities exist.

Tiri, or Mea, is an Oceanic language of New Caledonia.

Matis is a language spoken by the indigenous Matis people in the state of Amazonas in Brazil.

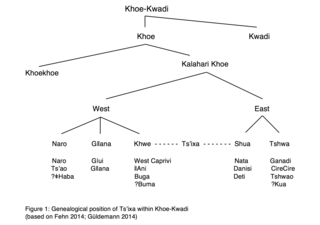

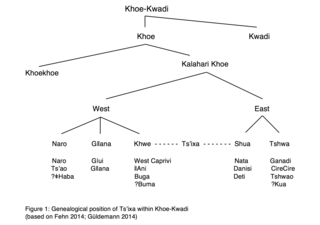

Tsʼixa is a critically endangered African language that belongs to the Kalahari Khoe branch of the Khoe-Kwadi language family. The Tsʼixa speech community consists of approximately 200 speakers who live in Botswana on the eastern edge of the Okavango Delta, in the small village of Mababe. They are a foraging society that consists of the ethnically diverse groups commonly subsumed under the names "San", "Bushmen" or "Basarwa". The most common term of self-reference within the community is Xuukhoe or 'people left behind', a rather broad ethnonym roughly equaling San, which is also used by Khwe-speakers in Botswana. Although the affiliation of Tsʼixa within the Khalari Khoe branch, as well as the genetic classification of the Khoisan languages in general, is still unclear, the Khoisan language scholar Tom Güldemann posits in a 2014 article the following genealogical relationships within Khoe-Kwadi, and argues for the status of Tsʼixa as a language in its own right. The language tree to the right presents a possible classification of Tsʼixa within Khoe-Kwadi:

Turkmen grammar is the grammar of the Turkmen language, whose dialectal variants are spoken in Turkmenistan, Iran, Afghanistan, Russia, China, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and others. Turkmen grammar, as described in this article, is the grammar of standard Turkmen as spoken and written by Turkmen people in Turkmenistan.