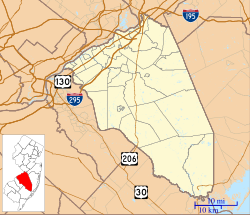

The school was founded in 1886 in the New Brunswick house of the Rev. Walter A. Rice, a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and former slave from Laurens, South Carolina. Born in 1845, Rice had fought as a volunteer with the Union Army during the American Civil War and went to New Jersey to get an education, after completing his military service. [3] [4] When it was first founded, it was known as "The Ironsides Normal School". [4] The school's mission was to train African-American students "in such industries as shall enable them to become self-supporting". [5] The state passed legislation in 1894 to designate the school as the state's instructional institution for vocational education. With this legislation, the school was placed under the aegis of a board of trustees composed of state and county officials. The school came under the direct auspices of the New Jersey Board of Education in 1903, with its capital expenditures, curriculum and staffing under state approval. [4] In 1886, the school moved to Bordentown and moved in 1896 to a 400-acre (1.6 km2) tract there that had been owned by United States Navy Admiral Charles Stewart and known as the Parnell Estate. [3] [5] The state originally leased the land, and purchased it in 1901. [4]

The school operated on a year-round basis. It had its own farm, cattle, and orchards that supplied the school with its food; scholarship students could work on the farm to cover their tuition. The school was selective and initially offered its 500 to 600 students an education in the Classics and Latin as part of its overall curriculum, which earned accolades from both W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Among notable lecturers at the school were Albert Einstein and Paul Robeson. [3] In 1897, James Monroe Gregory became principal at Bordentown. Gregory had been a Latin Professor and Dean at Howard University. [6] [7] Gregory served until 1915. [8] In 1913, Booker T. Washington recommended that the school identify occupations prevalent among African-Americans as a guide to developing a curriculum for the school, suggesting that training in automobile repairs for boys would help meet the growing demand for chauffeurs, while girls should be offered "domestic science" training. [9] Students were instructed in a trade in addition to the educational curriculum, with boys instructed in agriculture, auto mechanics, and steam boiler operation, and girls being taught beauty culture, dressmaking, and sewing. During the Great Depression, Bordentown graduates were better able than many to find jobs using the skills they had learned at the school. [10]

Because of financial difficulties, the school accepted state aid and was ultimately taken over by the State of New Jersey in 1897 and placed under the supervision of the New Jersey Department of Education in 1945. William R. Valentine, a graduate of both Columbia University and Harvard University, served as the school's principal from 1915 at least until 1948. Valentine stressed the approach of offering practical job training as a means to prevent students from becoming juvenile delinquents. [11]

Demise and closure

After the passage of the 1947 New Jersey State Constitution, the term "for Colored Youth" was removed from the school's name and it became formally known as the "State of New Jersey Manual Training School" or "Manual Training and Industrial School for Youth" and was opened to students of all races as of 1948. [4] [11] In what was called "an example of desegregation in reverse" by The New York Times , Governor of New Jersey Robert B. Meyner ordered that the school be closed in June 1955, citing the school's failure to recruit and retain white students. [12] The closing of the school ended segregation in the state's schools, which had persisted in many South Jersey school districts as late as 1952. In 1956, the site was slated to undergo a conversion to become a school for the developmentally disabled, which was estimated to cost as much as $3 million. The New York Times noted that the facilities were in disrepair, and that some buildings would require extensive repairs, while at least two minor structures were to be demolished. [13] As of 2000, the buildings on the site were being used by the New Jersey Department of Corrections; many of the original buildings were in a dilapidated state. [3]

The school was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998. [14] It was the subject of David Davidson's 2009 documentary film A Place Out of Time — The Bordentown School, narrated by Ruby Dee and broadcast on PBS in May 2010. [10]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.