Anaximander was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus, a city of Ionia. He belonged to the Milesian school and learned the teachings of his master Thales. He succeeded Thales and became the second master of that school where he counted Anaximenes and, arguably, Pythagoras amongst his pupils.

Anaximenes of Miletus was an Ancient Greek, Pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Anatolia. He was the last of the three philosophers of the Milesian School, after Thales and Anaximander. These three are regarded by historians as the first philosophers of the Western world. Anaximenes is known for his belief that air is the arche, or the basic element of the universe from which all things are created. Little is known of Anaximenes's life and work, as all of his original texts are lost. Historians and philosophers have reconstructed information about Anaximenes by interpreting texts about him by later writers. All three Milesian philosophers were monists who believed in a single foundational source of everything: Anaximenes believed it to be air, while Thales and Anaximander believed it to be water and an undefined infinity, respectively. It is generally accepted that Anaximenes was instructed by Anaximander, and many of their philosophical ideas are similar. While Anaximenes was the preeminent Milesian philosopher in Ancient Greece, he is often given lower importance than the others in the modern day.

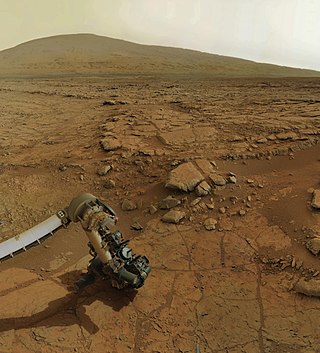

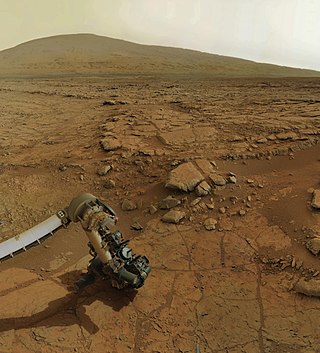

Extraterrestrial life, or alien life, is life which does not originate from Earth. No extraterrestrial life has yet been scientifically conclusively detected. Such life might range from simple forms such as prokaryotes to intelligent beings, possibly bringing forth civilizations that might be far more advanced than humans. The Drake equation speculates about the existence of sapient life elsewhere in the universe. The science of extraterrestrial life is known as astrobiology.

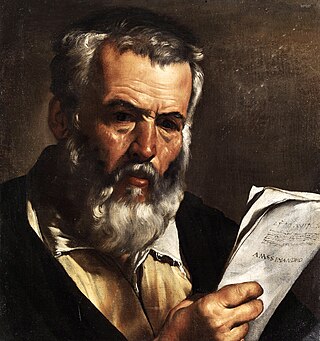

Giordano Bruno was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which conceptually extended to include the then-novel Copernican model. He practiced Hermeticism and gave a mystical stance to exploring the universe. He proposed that the stars were distant suns surrounded by their own planets (exoplanets), and he raised the possibility that these planets might foster life of their own, a cosmological position known as cosmic pluralism. He also insisted that the universe is infinite and could have no center.

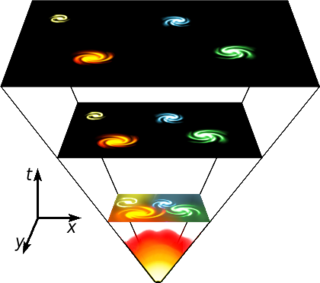

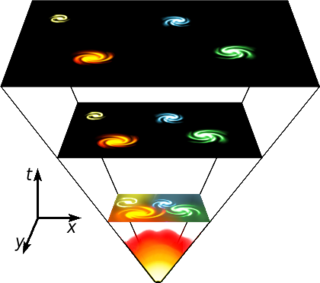

The multiverse is the hypothetical set of all universes. Together, these universes are presumed to comprise everything that exists: the entirety of space, time, matter, energy, information, and the physical laws and constants that describe them. The different universes within the multiverse are called "parallel universes", "flat universes", "other universes", "alternate universes", "multiple universes", "plane universes", "parent and child universes", "many universes", or "many worlds". One common assumption is that the multiverse is a "patchwork quilt of separate universes all bound by the same laws of physics."

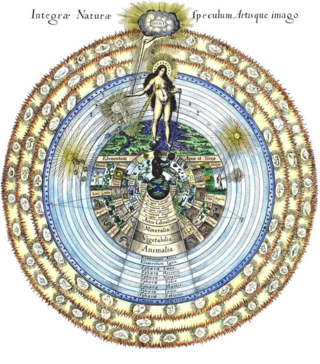

The cosmos is an alternative name for the universe or its nature or order. Usage of the word cosmos implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

This timeline of cosmological theories and discoveries is a chronological record of the development of humanity's understanding of the cosmos over the last two-plus millennia. Modern cosmological ideas follow the development of the scientific discipline of physical cosmology.

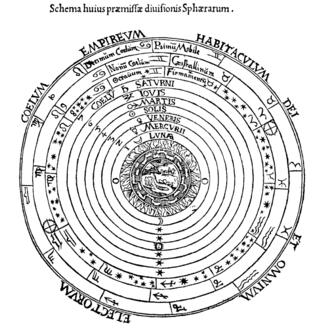

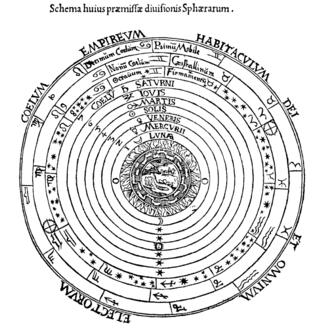

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the apparent motions of the fixed stars and planets are accounted for by treating them as embedded in rotating spheres made of an aetherial, transparent fifth element (quintessence), like gems set in orbs. Since it was believed that the fixed stars did not change their positions relative to one another, it was argued that they must be on the surface of a single starry sphere.

Nicolas Camille Flammarion FRAS was a French astronomer and author. He was a prolific author of more than fifty titles, including popular science works about astronomy, several notable early science fiction novels, and works on psychical research and related topics. He also published the magazine L'Astronomie, starting in 1882. He maintained a private observatory at Juvisy-sur-Orge, France.

The term "exotheology" was coined in the 1960s or early 1970s for the examination of theological issues as they pertain to extraterrestrial intelligence. It is primarily concerned with either conjecture about possible theological beliefs that extraterrestrials might have, or how our own theologies would be influenced by evidence of and/or interaction with extraterrestrials.

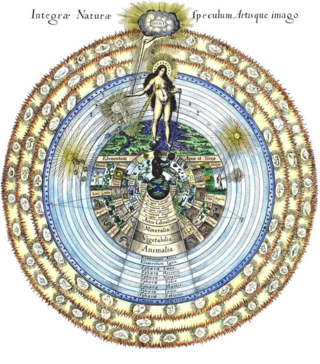

The concept of the anima mundi (Latin), world soul, or soul of the world posits an intrinsic connection between all living beings, suggesting that the world is animated by a soul much like the human body. Rooted in ancient Greek and Roman philosophy, the idea holds that the world soul infuses the cosmos with life and intelligence. This notion has been influential across various systems of thought, including Stoicism, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, and Hermeticism, shaping metaphysical and cosmological frameworks throughout history.

Creatio ex nihilo is the doctrine that matter is not eternal but had to be created by some divine creative act. It is a theistic answer to the question of how the universe came to exist. It is in contrast to creation ex materia, sometimes framed in terms of the dictum Ex nihilo nihil fit or "nothing comes from nothing", meaning all things were formed ex materia.

Cosmology is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term cosmology was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's Glossographia, and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher Christian Wolff in Cosmologia Generalis. Religious or mythological cosmology is a body of beliefs based on mythological, religious, and esoteric literature and traditions of creation myths and eschatology. In the science of astronomy, cosmology is concerned with the study of the chronology of the universe.

In ancient near eastern cosmology, the firmament means a celestial barrier that separated the heavenly waters above from the Earth below. In biblical cosmology, the firmament is the vast solid dome created by God during the Genesis creation narrative to separate the primal sea into upper and lower portions so that the dry land could appear.

The Ionian school of pre-Socratic philosophy refers to Ancient Greek philosophers, or a school of thought, in Ionia in the 6th century B.C, the first in the Western tradition.

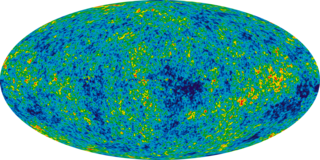

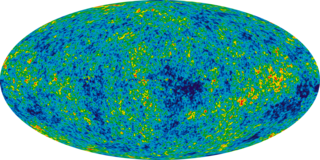

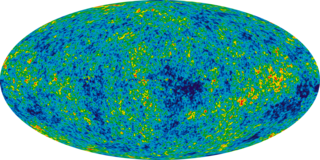

The history of the Big Bang theory began with the Big Bang's development from observations and theoretical considerations. Much of the theoretical work in cosmology now involves extensions and refinements to the basic Big Bang model. The theory itself was originally formalised by Father Georges Lemaître in 1927. Hubble's law of the expansion of the universe provided foundational support for the theory.

Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds is a popular science book by French author Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle, published in 1686.

Philosophers throughout the history of philosophy have been held in courts and tribunals for various offenses, often as a result of their philosophical activity, and some have even been put to death. The most famous example of a philosopher being put on trial is the case of Socrates, who was tried for, amongst other charges, corrupting the youth and impiety.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to extraterrestrial life:

The existence of extraterrestrial life is a scientific idea that has been debated for centuries. Initially, the question was purely speculative; in modern times a limited amount of scientific evidence provides some answers. The idea was first proposed in Ancient Greece, where it was supported by atomists and rejected by Aristotelians. The debate continued during the Middle Ages, when the discussion centered upon whether the notion of extraterrestrial life was compatible with the doctrines of Christianity. The Copernican Revolution radically altered mankind's image of the architecture of the cosmos by removing Earth from the center of the universe, which made the concept of extraterrestrial life more plausible. Today we have no conclusive evidence of extraterrestrial life, but experts in many different disciplines gather to study the idea under the scientific umbrella of astrobiology.