A Martian meteorite is a rock that formed on Mars, was ejected from the planet by an impact event, and traversed interplanetary space before landing on Earth as a meteorite. As of September 2020, 277 meteorites had been classified as Martian, less than half a percent of the 72,000 meteorites that have been classified. The largest complete, uncut Martian meteorite, Taoudenni 002, was recovered in Mali in early 2021. It weighs 14.5 kilograms and is on display at the Maine Mineral and Gem Museum.

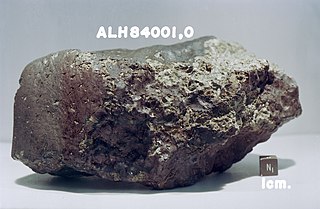

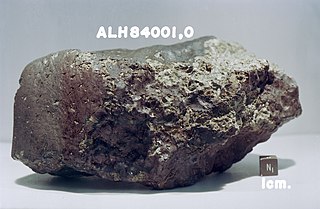

Allan Hills 84001 (ALH84001) is a fragment of a Martian meteorite that was found in the Allan Hills in Antarctica on December 27, 1984, by a team of American meteorite hunters from the ANSMET project. Like other members of the shergottite–nakhlite–chassignite (SNC) group of meteorites, ALH84001 is thought to have originated on Mars. However, it does not fit into any of the previously discovered SNC groups. Its mass upon discovery was 1.93 kilograms (4.3 lb).

The possibility of life on Mars is a subject of interest in astrobiology due to the planet's proximity and similarities to Earth. To date, no conclusive evidence of past or present life has been found on Mars. Cumulative evidence suggests that during the ancient Noachian time period, the surface environment of Mars had liquid water and may have been habitable for microorganisms, but habitable conditions do not necessarily indicate life.

The Astrobiology Field Laboratory (AFL) was a proposed NASA rover that would have conducted a search for life on Mars. This proposed mission, which was not funded, would have landed a rover on Mars in 2016 and explore a site for habitat. Examples of such sites are an active or extinct hydrothermal deposit, a dry lake or a specific polar site.

NASA's 2003 Mars Exploration Rover Mission has amassed an enormous amount of scientific information related to the Martian geology and atmosphere, as well as providing some astronomical observations from Mars. This article covers information gathered by the Opportunity rover during the initial phase of its mission. Information on science gathered by Spirit can be found mostly in the Spirit rover article.

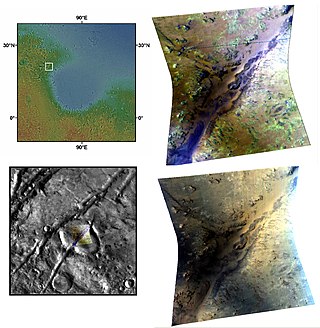

The Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars (CRISM) was a visible-infrared spectrometer aboard the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter searching for mineralogic indications of past and present water on Mars. The CRISM instrument team comprised scientists from over ten universities and was led by principal investigator Scott Murchie. CRISM was designed, built, and tested by the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

The formation of carbonates on Mars have been suggested based on evidence of the presence of liquid water and atmospheric carbon dioxide in the planet's early stages. Moreover, due to their utility in registering changes in environmental conditions such as pH, temperature, fluid composition, carbonates have been considered as a primary target for planetary scientists' research. However, since their first detection in 2008, the large deposits of carbonates that were once expected on Mars have not been found, leading to multiple potential explanations that can explain why carbonates did not form massively on the planet.

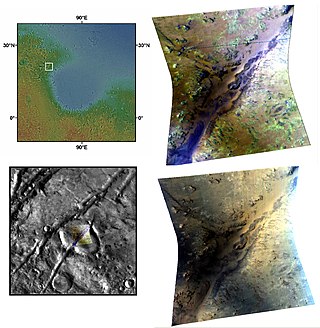

Nili Fossae is a group of large, concentric grabens on Mars, in the Syrtis Major quadrangle. They have been eroded and partly filled in by sediments and clay-rich ejecta from a nearby giant impact crater, the Isidis basin. It is at approximately 22°N, 75°E, and has an elevation of −0.6 km (−0.37 mi).

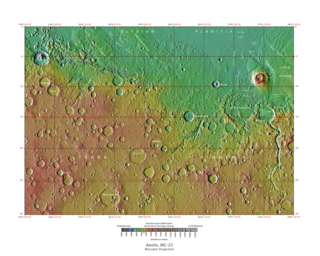

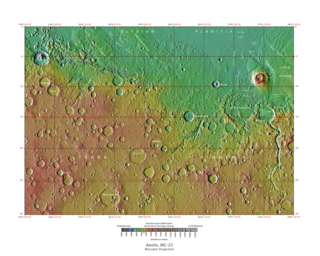

The Aeolis quadrangle is one of a series of 30 quadrangle maps of Mars used by the United States Geological Survey (USGS) Astrogeology Research Program. The Aeolis quadrangle is also referred to as MC-23 . The Aeolis quadrangle covers 180° to 225° W and 0° to 30° south on Mars, and contains parts of the regions Elysium Planitia and Terra Cimmeria. A small part of the Medusae Fossae Formation lies in this quadrangle.

Almost all water on Mars today exists as polar permafrost ice, though it also exists in small quantities as vapor in the atmosphere.

Mars may contain ores that would be very useful to potential colonists. The abundance of volcanic features together with widespread cratering are strong evidence for a variety of ores. While nothing may be found on Mars that would justify the high cost of transport to Earth, the more ores that future colonists can obtain from Mars, the easier it would be to build colonies there.

Nakhlites are a group of Martian meteorites, named after the first one, Nakhla meteorite.

The composition of Mars covers the branch of the geology of Mars that describes the make-up of the planet Mars.

The Tissint meteorite is a Martian meteorite that fell in Tata Province in the Guelmim-Es Semara region of Morocco on July 18, 2011. Tissint is the fifth Martian meteorite that people have witnessed falling to Earth, and the first since 1962. Pieces of the meteorite are on display at several museums, including the Museum of Natural History of Vienna and the Natural History Museum in London.

Northwest Africa 7034 is a Martian meteorite. It contains portions estimated to be 4.43 billion years old and contains the most water of any Martian meteorite found on Earth. Although it is from Mars it does not fit into any of the three SNC meteorite categories, and forms a new Martian meteorite group named "Martian ". Nicknamed "Black Beauty", it was purchased in Morocco and a slice of it was donated to the University of New Mexico by its American owner. The image of the original NWA 7034 was photographed in 2012 by Carl Agee, University of New Mexico.

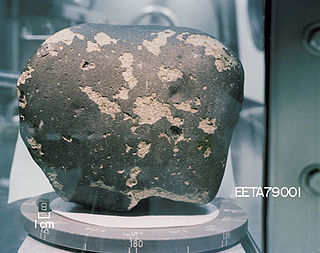

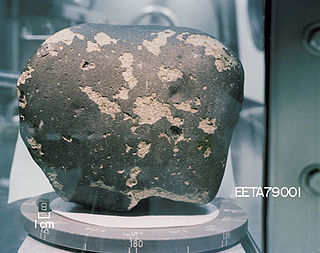

Elephant Moraine 79001, also known as EETA 79001, is a Martian meteorite. It was found in Elephant Moraine, in the Antarctic during the 1979–1980 collecting season.

Yamato 000593 is the second largest meteorite from Mars found on Earth. Studies suggest the Martian meteorite was formed about 1.3 billion years ago from a lava flow on Mars. An impact occurred on Mars about 11 million years ago and ejected the meteorite from the Martian surface into space. The meteorite landed on Earth in Antarctica about 50,000 years ago. The mass of the meteorite is 13.7 kg (30 lb) and has been found to contain evidence of past water alteration.

Bethany List Ehlmann is an American geologist and a professor of Planetary Science at California Institute of Technology. A leading researcher in planetary geology, Ehlmann is also the President of The Planetary Society, Director of the Keck Institute for Space Studies, and a Research Scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Allan Hills 77005 is a Martian meteorite that was found in the Allan Hills of Antarctica in 1977 by a Japanese National Institute of Polar Research mission team and ANSMET. Like other members of the group of SNCs, ALH-77005 is thought to be from Mars.