Related Research Articles

The subjunctive is a grammatical mood, a feature of an utterance that indicates the speaker's attitude toward it. Subjunctive forms of verbs are typically used to express various states of unreality such as wish, emotion, possibility, judgment, opinion, obligation, or action that has not yet occurred; the precise situations in which they are used vary from language to language. The subjunctive is one of the irrealis moods, which refer to what is not necessarily real. It is often contrasted with the indicative, a realis mood which principally indicates that something is a statement of fact.

Insular Celtic languages are the group of Celtic languages spoken in Brittany, Great Britain, Ireland, and the Isle of Man. All surviving Celtic languages are in the Insular group, including Breton, which is spoken on continental Europe in Brittany, France. The Continental Celtic languages, although once widely spoken in mainland Europe and in Anatolia, are extinct.

Old Irish, also called Old Gaelic, is the oldest form of the Goidelic/Gaelic language for which there are extensive written texts. It was used from c. 600 to c. 900. The main contemporary texts are dated c. 700–850; by 900 the language had already transitioned into early Middle Irish. Some Old Irish texts date from the 10th century, although these are presumably copies of texts written at an earlier time. Old Irish is thus forebear to Modern Irish, Manx and Scottish Gaelic.

Irish syntax is rather different from that of most Indo-European languages, especially because of its VSO word order.

Swampy Cree is a variety of the Algonquian language, Cree. It is spoken in a series of Swampy Cree communities in northern Manitoba, central northeast of Saskatchewan along the Saskatchewan River and along the Hudson Bay coast and adjacent inland areas to the south and west, and Ontario along the coast of Hudson Bay and James Bay. Within the group of dialects called "West Cree", it is referred to as an "n-dialect", as the variable phoneme common to all Cree dialects appears as "n" in this dialect.

Tariana is an endangered Maipurean language spoken along the Vaupés River in Amazonas, Brazil by approximately 100 people. Another approximately 1,500 people in the upper and middle Vaupés River area identify themselves as ethnic Tariana but do not speak the language fluently.

The Ojibwe language is an Algonquian North American indigenous language spoken throughout the Great Lakes region and westward onto the northern plains. It is one of the largest indigenous language north of Mexico in terms of number of speakers, and exhibits a large number of divergent dialects. For the most part, this article describes the Minnesota variety of the Southwestern dialect. The orthography used is the Fiero Double-Vowel System.

Tiipai (Tipay) is a Native American language belonging to the Delta–California branch of the Yuman language family, which spans Arizona, California, and Baja California. As part of the Yuman family, Tiipai has also been consistently included in the controversial quasi-stock Hokan. Tiipai is spoken by a number of Kumeyaay tribes in northern Baja California and southern San Diego County, California. There were, conservatively, 200 Tiipai speakers in the early 1990s; the number of speakers has since declined steadily, numbering roughly 100 speakers in Baja California in a 2007 survey.

Araki is a nearly extinct language spoken in the small island of Araki, south of Espiritu Santo Island in Vanuatu. Araki is gradually being replaced by Tangoa, a language from a neighbouring island.

Early Middle Japanese is a stage of the Japanese language between 794 and 1185, which is known as the Heian period (平安時代). The successor to Old Japanese (上代日本語), it is also known as Late Old Japanese. However, the term "Early Middle Japanese" is preferred, as it is closer to Late Middle Japanese than to Old Japanese.

Misantla Totonac, also known as Yecuatla Totonac and Southeastern Totonac, is an indigenous language of Mexico, spoken in central Veracruz in the area between Xalapa and Misantla. It belongs to the Totonacan family and is the southernmost variety of Totonac. Misantla Totonac is highly endangered, with fewer than 133 speakers, most of whom are elderly. The language has largely been replaced by Spanish.

Maliseet-Passamaquoddy is an endangered Algonquian language spoken by the Wolastoqey and Passamaquoddy peoples along both sides of the border between Maine in the United States and New Brunswick, Canada. The language consists of two major dialects: Maliseet, which is mainly spoken in the Saint John River Valley in New Brunswick; and Passamaquoddy, spoken mostly in the St. Croix River Valley of eastern Maine. However, the two dialects differ only slightly, mainly in their phonology. The indigenous people widely spoke Maliseet-Passamaquoddy in these areas until around the post-World War II era when changes in the education system and increased marriage outside of the speech community caused a large decrease in the number of children who learned or regularly used the language. As a result, in both Canada and the U.S. today, there are only 600 speakers of both dialects, and most speakers are older adults. Although the majority of younger people cannot speak the language, there is growing interest in teaching the language in community classes and in some schools.

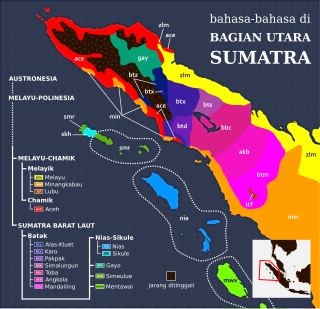

The Nias language is an Austronesian language spoken on Nias Island and the Batu Islands off the west coast of Sumatra in Indonesia. It is known as Li Niha by its native speakers. It belongs to the Northwest Sumatra–Barrier Islands subgroup which also includes Mentawai and the Batak languages. It had about 770,000 speakers in 2000. There are three main dialects: northern, central and southern. It is an open-syllable language, which means there are no syllable-final consonants.

In linguistics, grammatical mood is a grammatical feature of verbs, used for signaling modality. That is, it is the use of verbal inflections that allow speakers to express their attitude toward what they are saying. The term is also used more broadly to describe the syntactic expression of modality – that is, the use of verb phrases that do not involve inflection of the verb itself.

The Pauna language, Paunaca, Paunaka, is an Arawakan language in South America. It is an extremely endangered language, which belongs to the southern branch of the Arawakan language family and it is spoken in the Bolivian area of the Chiquitanía, near Santa Cruz and north of the Chaco region. The suffix -ka is a plural morpheme of the Chiquitano language, but has been assimilated into Pauna.

Tawala is an Oceanic language of the Milne Bay Province, Papua New Guinea. It is spoken by 20,000 people who live in hamlets and small villages on the East Cape peninsula, on the shores of Milne Bay and on areas of the islands of Sideia and Basilaki. There are approximately 40 main centres of population each speaking the same dialect, although through the process of colonisation some centres have gained more prominence than others.

Torricelli, Anamagi or Lou, is a Torricelli language of East Sepik province, Papua New Guinea. Drinfield describes it as containing three distinct, but related languages: Mukweym, Orok, and Aro.

Neverver (Nevwervwer), also known as Lingarak, is an Oceanic language. Neverver is spoken in Malampa Province, in central Malekula, Vanuatu. The names of the villages on Malekula Island where Neverver is spoken are Lingarakh and Limap.

This article describes the grammar of the Old Irish language. The grammar of the language has been described with exhaustive detail by various authors, including Thurneysen, Binchy and Bergin, McCone, O'Connell, Stifter, among many others.

The grammar of the Manx language has much in common with related Indo-European languages, such as nouns that display gender, number and case and verbs that take endings or employ auxiliaries to show tense, person or number. Other morphological features are typical of Insular Celtic languages but atypical of other Indo-European languages. These include initial consonant mutation, inflected prepositions and verb–subject–object word order.

References

- 1 2 3 4 McCone, Kim (1987). The Early Irish Verb. Maynooth: An Sagart. ISBN 1-870684-00-1 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- 1 2 Thurneysen, Rudolf (1993) [1946]. A Grammar of Old Irish. Translated by D. A. Binchy and Osborn Bergin. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 1-85500-161-6 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- 1 2 McCone, Kim (2005). A First Old Irish Grammar and Reader. Maynooth: Department of Old and Middle Irish, National University of Ireland. ISBN 0-901519-36-7 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ↑ Green, Antony (1995). Old Irish Verbs and Vocabulary. Somerville, Mass.: Cascadilla Press. p. 73. ISBN 1-57473-003-7 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ↑ Cowgill, Warren (1975). "The origins of the Insular Celtic conjunct and absolute verbal endings". In H. Rix (ed.). Flexion und Wortbildung: Akten der V. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, Regensburg, 9.–14. September 1973. Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 40–70. ISBN 3-920153-40-5.

- 1 2 Calder, George (1923). A Gaelic Grammar. Glasgow: MacLaren & Sons. Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ↑ Mackinnon, Roderick. Gaelic. London: Teach Yourself Books. ISBN 0-340-15153-6 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ↑ Broderick, George (1993). "Manx". In M.J. Ball; J. Fife (eds.). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 228–85. ISBN 0-415-01035-7 . Retrieved 2013-04-06.

- ↑ Broderick, George (1984–86). A Handbook of Late Spoken Manx. Vol. 1. Tübingen: Niemeyer. ISBN 3-484-42903-8 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- 1 2 McManus, Damian (1994). "An Nua-Ghaeilge Chlasaiceach". In K. McCone; D. McManus; C. Ó. Háinle; N. Williams; L. Breatnach (eds.). Stair na Gaeilge in ómós do Pádraig Ó Fiannachta (in Irish). Maynooth: Department of Old Irish, St. Patrick's College. pp. 335–445. ISBN 0-901519-90-1 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- 1 2 Christian Brothers (1994). New Irish Grammar. Dublin: C. J. Fallon. ISBN 0-7144-1298-8 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.

- ↑ Ó Siadhail, Mícheál (1989). Modern Irish: Grammatical structure and dialectal variation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37147-3 . Retrieved 2009-03-05.