El Cortez | |

El Cortez in 2009 | |

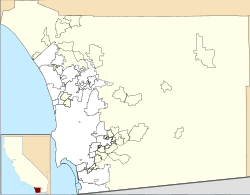

| Location | San Diego, California |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 32°43′13″N117°9′29″W / 32.72028°N 117.15806°W |

| Built | 1927 |

| Architect | Walker & Eisen; Simpson, William, Construction Co. |

| Architectural style | Mission/Spanish Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 01001458 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | January 17, 2002 |

El Cortez is a condominium building in San Diego, California. Built from 1926 to 1927, El Cortez was the tallest building in San Diego when it opened. It sits atop a hill at the north end of downtown San Diego, where it dominated the city skyline for many years and became a landmark hotel. The building is the 40th tallest building in San Diego, based on its height of 310 ft (94 m).

Contents

- Early history (1927–1949)

- Construction and architecture

- World War II

- Handlery years (1950–1978)

- Harry Handlery

- Glass elevator and Travolator

- Paul Handlery

- Pueblo incident

- Cerullo's evangelism center (1978–1981)

- Later years

- Considine years and convention center proposal

- Preservation efforts

- Redevelopment into condominiums

- Intellectual property

- Impact

- References

- External links

From its opening in 1927 through the 1950s, it was a renowned apartment-hotel in San Diego. The large "El Cortez" sign, which is illuminated at night, was added in 1937 and could be seen for miles. In the 1950s, the world's first outside glass elevator was built at El Cortez. During the late 1960s and 1970s, El Cortez fell on harder times.

El Cortez closed as a hotel in 1978 when it was purchased by evangelist Morris Cerullo to serve as an evangelism school. Cerullo sold the property in 1981, and El Cortez was threatened with demolition until the San Diego Historic Site Board designated it as a historic site in 1990. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. Many of the original elements remain in place, though substantial interior modifications have been made.