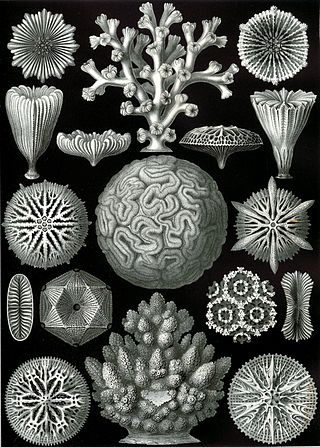

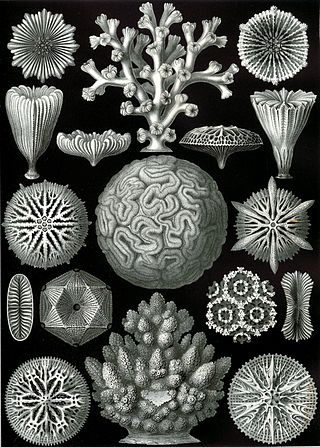

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and secrete calcium carbonate to form a hard skeleton.

Scleractinia, also called stony corals or hard corals, are marine animals in the phylum Cnidaria that build themselves a hard skeleton. The individual animals are known as polyps and have a cylindrical body crowned by an oral disc in which a mouth is fringed with tentacles. Although some species are solitary, most are colonial. The founding polyp settles and starts to secrete calcium carbonate to protect its soft body. Solitary corals can be as much as 25 cm (10 in) across but in colonial species the polyps are usually only a few millimetres in diameter. These polyps reproduce asexually by budding, but remain attached to each other, forming a multi-polyp colony of clones with a common skeleton, which may be up to several metres in diameter or height according to species.

The Staghorn coral is a branching, stony coral, within the Order Scleractinia. It is characterized by thick, upright branches which can grow in excess of 2 meters in height and resemble the antlers of a stag, hence the name, Staghorn. It grows within various areas of a reef but is most commonly found within shallow fore and back reefs, as well as patch reefs, where water depths rarely exceed 20 meters. Staghorn corals can exhibit very fast growth, adding up to 5 cm in new skeleton for every 1 cm of existing skeleton each year, making them one of the fastest growing fringe coral species in the Western Atlantic. Due to this fast growth, Acropora cervicornis, serve as one of the most important reef building corals, functioning as marine nurseries for juvenile fish, buffer zones for erosion and storms, and center points of biodiversity in the Western Atlantic.

Montipora is a genus of Scleractinian corals in the phylum Cnidaria. Members of the genus Montipora may exhibit many different growth morphologies. With eighty five known species, Montipora is the second most species rich coral genus after Acropora.

Millepora dichotoma, the net fire coral, is a species of hydrozoan, consisting of a colony of polyps with a calcareous skeleton.

Galaxea fascicularis is a species of colonial stony coral in the family Euphylliidae, commonly known as Octopus coral, Fluorescence grass coral, and Galaxy coral among various vernacular names.

Millepora platyphylla is a species of fire coral, a type of hydrocoral, in the family Milleporidae. It is also known by the common names blade fire coral and plate fire coral. It forms a calcium carbonate skeleton and has toxic, defensive polyps that sting. It obtains nutrients by consuming plankton and via symbiosis with photosynthetic algae. The species is found from the Red Sea and East Africa to northern Australia and French Polynesia. It plays an important role in reef-building in the Indo-Pacific region. Depending on its environment, it can have a variety of different forms and structures.

Diploria is a monotypic genus of massive reef building stony corals in the family Mussidae. It is represented by a single species, Diploria labyrinthiformis, commonly known as grooved brain coral and is found in the western Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean Sea. It has a familiar, maze-like appearance.

Euphyllia ancora is a species of hard coral in the family Euphylliidae. It is known by several common names, including anchor coral and hammer coral, or less frequently as sausage coral, ridge coral, or bubble honeycomb coral.

A mesophotic coral reef or mesophotic coral ecosystem (MCE), originally from the Latin word meso (meaning middle) and photic (meaning light), is characterized by the presence of both light-dependent coral and algae, and organisms that can be found in water with low light penetration. Mesophotic coral ecosystems occur at depths beyond those typically associated with coral reefs as the mesophotic ranges from brightly lit to some areas where light does not reach. Mesophotic coral ecosystem (MCEs) is a new, widely-adopted term used to refer to mesophotic coral reefs, as opposed to other similar terms like "deep coral reef communities" and "twilight zone", since those terms sometimes are confused due to their unclear, interchangeable nature. Many species of fish and corals are endemic to the MCEs making these ecosystems a crucial component in maintaining global diversity. Recently, there has been increased focus on the MCEs as these reefs are a crucial part of the coral reef systems serving as a potential refuge area for shallow coral reef taxa such as coral and sponges. Advances in recent technologies such as remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs) have enabled humans to conduct further research on these ecosystems and monitor these marine environments.

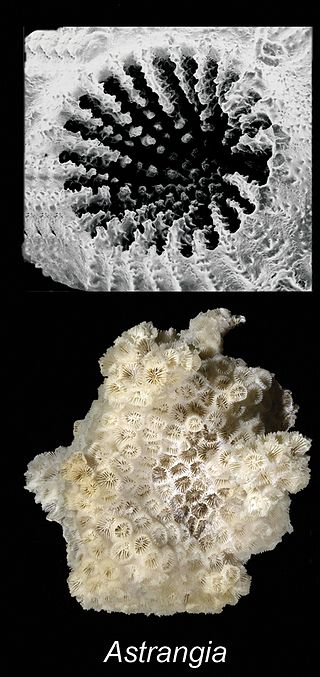

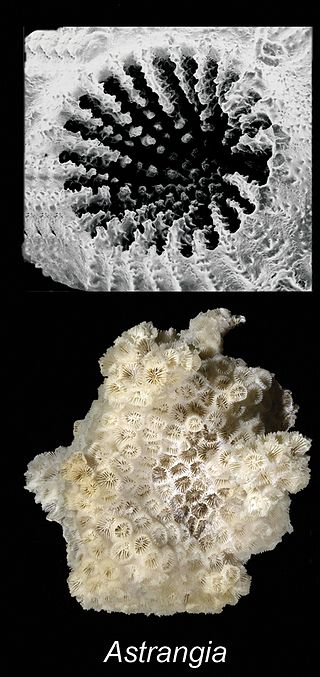

Astrangia poculata, the northern star coral or northern cup coral, is a species of non-reefbuilding stony coral in the family Rhizangiidae. It is native to shallow water in the western Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea. It is also found on the western coast of Africa. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists this coral as being of "least concern". Astrangia poculata is an emerging model organism for corals because it harbors a facultative photosymbiosis, is a calcifying coral, and has a large geographic range. Research on this emerging model system is showcased annually by the Astrangia Research Working Group, collaboratively hosted by Roger Williams University, Boston University, and Southern Connecticut State University

Coelastrea aspera is a species of stony coral in the family Merulinidae. It is a colonial species native to the Indo-Pacific region where it occurs in shallow water. It was first described by the American zoologist Addison Emery Verrill in 1866 as Goniastrea aspera but it has since been determined that it should be in a different genus and its scientific name has been changed to Coelastrea aspera. This is a common species throughout much of its wide range and the International Union for Conservation of Nature has rated its conservation status as being of "least concern".

Porites cylindrica, commonly known as Hump coral, is a stony coral belonging to the subclass Hexacorallia in the class Anthozoa. Hexacorallia differ from other subclasses in that they have six or fewer axes of symmetry. Members of this class possess colonial polyps which can be reef-building, secreting a calcium carbonate skeleton. They are dominant in both inshore reefs and midshelf reefs.

Euphylliidae are known as a family of polyped stony corals under the order Scleractinia.

A corallivore is an animal that feeds on coral. Corallivores are an important group of reef organism because they can influence coral abundance, distribution, and community structure. Corallivores feed on coral using a variety of unique adaptations and strategies. Known corallivores include certain mollusks, annelids, fish, crustaceans, flatworms and echinoderms. The first recorded evidence of corallivory was presented by Charles Darwin in 1842 during his voyage on HMS Beagle in which he found coral in the stomach of two Scarus parrotfish.

Oxypora glabra is a species of large polyp stony coral in the family Lobophylliidae. It is a colonial coral with thin encrusting laminae. It is native to the central Indo-Pacific.

Pocillopora capitata, commonly known as the Cauliflower coral, is a principal hermatypic coral found in the Eastern Tropical Pacific. P. capitata is a colonial species of stony coral of the class Anthozoa, the order Scleractinia, and the family Pocilloporidae. This species was first documented and described by Addison Emery Verrill in 1864. P. capitata is threatened by many of the effects of climate change, including — but not limited to — increased temperatures that cause bleaching and hypoxic conditions.

Heterocyathus is a genus of coral of the family Caryophylliidae.

Heteropsammia is a genus of apozooxanthellate corals that belong to the family Dendrophylliidae.

Miguel Mies is a Brazilian academic, oceanographer, and researcher. He is currently a professor at the Oceanographic Institute of the University of São Paulo (IO-USP) and leads the Coral Reefs and Climate Change Laboratory (LARC). He also serves as the research coordinator for the Coral Vivo Project and is the vice president of the Coral Vivo Institute.