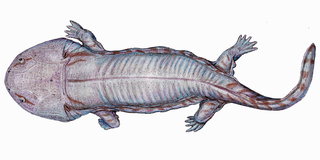

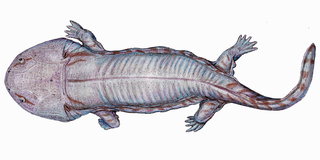

Temnospondyli or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered primitive amphibians—that flourished worldwide during the Carboniferous, Permian and Triassic periods, with fossils being found on every continent. A few species continued into the Jurassic and Early Cretaceous periods, but all had gone extinct by the Late Cretaceous. During about 210 million years of evolutionary history, they adapted to a wide range of habitats, including freshwater, terrestrial, and even coastal marine environments. Their life history is well understood, with fossils known from the larval stage, metamorphosis and maturity. Most temnospondyls were semiaquatic, although some were almost fully terrestrial, returning to the water only to breed. These temnospondyls were some of the first vertebrates fully adapted to life on land. Although temnospondyls are amphibians, many had characteristics such as scales and armour-like bony plates that distinguish them from the modern soft-bodied lissamphibians.

Mastodonsaurus is an extinct genus of temnospondyl from the Middle Triassic of Europe. It belongs to a Triassic group of temnospondyls called Capitosauria, characterized by their large body size and presumably aquatic lifestyles. Mastodonsaurus remains one of the largest amphibians known, and may have exceeded 6 meters in length.

The Stereospondyli are a group of extinct temnospondyl amphibians that existed primarily during the Mesozoic period. They are known from all seven continents and were common components of many Triassic ecosystems, likely filling a similar ecological niche to modern crocodilians prior to the diversification of pseudosuchian archosaurs.

Cochleosaurus (“spoon lizard”, from the Latin cochlear "spoon" and Greek sauros “lizard”_ were medium-sized edopoid temnospondyls that lived in Euramerica during the Muscovian period. Two species, C. bohemicus and C. florensis, have been identified from the fossil record.

Uranocentrodon is an extinct genus of temnospondyls in the family Rhinesuchidae. Known from a 50 centimetres (20 in) skull, Uranocentrodon was a large predator with a length up to 3.75 metres (12.3 ft). Originally named Myriodon by van Hoepen in 1911, it was transferred to a new genus on account of the name being preoccupied in 1917. It has been synonymized with Rhinesuchus, but this has not been widely supported. It was also originally considered to be of Triassic age, but more recent analysis has placed its age as just below the Permian-Triassic boundary.

Sclerocephalus is an extinct genus of temnospondyl amphibian from the lowermost Permian of Germany and Czech Republic with four valid species, including the type species S. haeuseri. It is one of the most completely preserved and most abundant Palaeozoic tetrapods. Sclerocephalus was once thought to be closely related to eryopoid temnospondyls, but it is now thought to be more closely related to archegosauroids. It is the only genus in the family Sclerocephalidae.

Laidleria is an extinct genus of temnospondyl that likely lived between the Early to Middle Triassic, though its exact stratigraphic range is less certain. Laidleria has been found in the Karoo Basin in South Africa, in Cynognathus Zone A or B. The genus is represented by only one species, L. gracilis, though the family Laidleriidae does include other genera, such as Uruyiella, sister taxon to Laidleria, which was discovered and classified in 2007.

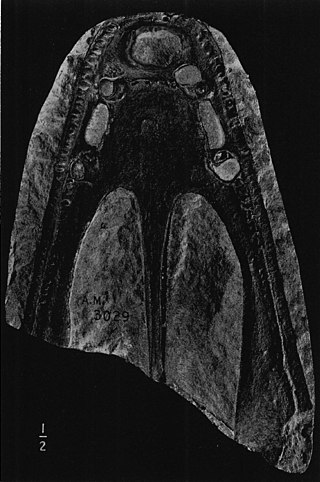

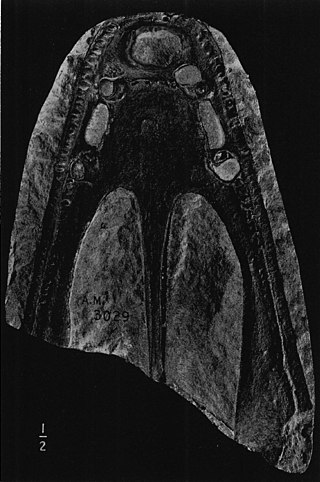

Spathicephalus is an extinct genus of stem tetrapods that lived during the middle of the Carboniferous Period. The genus includes two species: the type species S. mirus from Scotland, which is known from two mostly complete skulls and other cranial material, and the species S. pereger from Nova Scotia, which is known from a single fragment of the skull table. Based on the S. mirus material, the appearance of Spathicephalus is unlike that of any other early tetrapod, with a flattened, square-shaped skull and jaws lined with hundreds of very small chisel-like teeth. However, Spathicephalus shares several anatomical features with a family of stem tetrapods called Baphetidae, leading most paleontologists who have studied the genus to place it within a larger group called Baphetoidea, often as part of its own monotypic family Spathicephalidae. Spathicephalus is thought to have fed on aquatic invertebrates through a combination of suction feeding and filter feeding.

Eocyclotosaurus is an extinct genus of mastodonsauroid temnospondyl from the Middle Triassic (Anisian). The name Eocyclotosaurus means "dawn round-eared lizard". It is characterized as a capitosauroid with a long and slender snout, closed otic fenestra, and small orbits. It measured over one metre and had a 22 cm skull.

Plagiosauridae is a clade of temnospondyls of the Middle to Late Triassic. Deposits of the group are most commonly found in non-marine aquatic depositional environments from central Europe and Greenland, but other remains have been found in Russia, Scandinavia, and possibly Thailand.

Rhinesuchidae is a family of tetrapods that lived primarily in the Permian period. They belonged to the broad group Temnospondyli, a successful and diverse collection of semiaquatic tetrapods which modern amphibians are probably descended from. Rhinesuchids can be differentiated from other temnospondyls by details of their skulls, most notably the interior structure of their otic notches at the back of the skull. They were among the earliest-diverging members of the Stereospondyli, a subgroup of temnospondyls with flat heads and aquatic habits. Although more advanced stereospondyls evolved to reach worldwide distribution in the Triassic period, rhinesuchids primarily lived in the high-latitude environments of Gondwana during the Guadalupian and Lopingian epochs of the Permian. The taxonomy of this family has been convoluted, with more than twenty species having been named in the past; a 2017 review recognized only eight of them to be valid. While several purported members of this group have been reported to have lived in the Triassic period, most are either dubious or do not belong to the group. However, at least one valid genus of rhinesuchid is known from the early Triassic, a small member known as Broomistega. The most recent formal definition of Rhinesuchidae, advocated by Mariscano et al. (2017) is that of a stem-based clade containing all taxa more closely related to Rhinesuchus whaitsi than to Lydekkerina huxleyi or Peltobatrachus pustulatus. A similar alternate definition is that Rhinesuchidae is a stem-based clade containing all taxa more closely related to Uranocentrodon senekalensis than to Lydekkerina huxleyi, Trematosaurus brauni, or Mastodonsaurus giganteus.

Mastodonsauridae is a family of capitosauroid temnospondyls. Fossils belonging to this family have been found in North America, Greenland, Europe, Asia, and Australia. The family Capitosauridae is synonymous with Mastodonsauridae.

Rhineceps is an extinct genus of temnospondyl amphibian in the family Rhinesuchidae. Rhineceps was found in Northern Malawi in Southern Africa known only from its type species R. nyasaensis. Rhineceps was a late Permian semi-aquatic carnivore that lived in streams, rivers, lakes or lagoons. Rhineceps is an early divergent Stereopondyl within the family Rhinesuchidae, which only existed in the late Permian (Lopingian) and failed to survive the Permian-Triassic extinction unlike other stereospondyl families.

Plagiosuchus is an extinct genus of plagiosaurid temnospondyl. It is known from several collections from the Middle Triassic of Germany.

Stanocephalosaurus is an extinct genus of large-sized temnospondyls living through the early to mid Triassic. The etymology of its name most likely came from its long narrow skull when compared to other temnospondyls. Stanocephalosaurus lived an aquatic lifestyle, with some species even living in salt lakes. There are currently three recognized species and another that needs further material to establish its legitimacy. The three known species are Stanocephalosaurus pronus from the Middle Triassic in Tanzania, Stanocephalosaurus amenasensis from the Lower Triassic in Algeria, and Stanocephalosaurus birdi, from the middle Triassic in Arizona. Stanocephalosaurus rajareddyi from the Middle Triassic in central India needs further evidence in order to establish its relationship among other Stanocephalosaurs. Like other temnospondyls, Stanocephalosaurus was an aquatic carnivore. Evidence of multiple species discovered in a wide range of localities proves that Stanocephalosaurus were present all across Pangea throughout the early to mid Triassic.

Branchiosauridae is an extinct family of small amphibamiform temnospondyls with external gills and an overall juvenile appearance. The family has been characterized by hundreds of well-preserved specimens from the Permo-Carboniferous of Middle Europe. Specimens represent well defined ontogenetic stages and thus the taxon has been described to display paedomorphy (perennibranchiate). However, more recent work has revealed branchiosaurid taxa that display metamorphosing trajectories. The name Branchiosauridae refers to the retention of gills.

The Erfurt Formation, also known as the Lower Keuper, is a stratigraphic formation of the Keuper group and the Germanic Trias supergroup. It was deposited during the Ladinian stage of the Triassic period. It lies above the Upper Muschelkalk and below the Middle Keuper.

Megalophthalma is an extinct genus of temnospondyl amphibian belonging to the family Plagiosauridae. It is represented by the single type species Megalophthalma ockerti from the Middle Triassic Erfurt Formation in southern Germany, which is itself based on a single partial skull and a fragment of the lower jaw. Megalophthalma is distinguished from other temnospondyls by its very large orbits or eye sockets, which occupy most of the skull and are bordered by thin struts of bone. Like those of most plagiosaurids, the skull flat, wide, and roughly triangular. The orbits are pentagon-shaped. The bones at the back of the skull are highly modified and show similarities with those of the plagiosaurid Plagiosternum. Both Megalophthalma and Plagiosternum lack prefrontal and postfrontal bones. In fact, Megalophthalma and Plagiosternum are thought to form their own clade or evolutionary grouping within Plagiosauridae called Plagiosterninae. In overall form Megalophthalma and Plagiosternum are intermediate between the basal plagiosaurid Plagiosuchus and the derived Gerrothorax.

This list of fossil amphibians described in 2018 is a list of new taxa of fossil amphibians that were described during the year 2018, as well as other significant discoveries and events related to amphibian paleontology that occurred in 2018.