Savannah is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the British colonial capital of the Province of Georgia and later the first state capital of Georgia. A strategic port city in the American Revolution and during the American Civil War, Savannah is today an industrial center and an important Atlantic seaport. It is Georgia's fifth-most-populous city, with a 2020 U.S. census population of 147,780. The Savannah metropolitan area, Georgia's third-largest, had a 2020 population of 404,798.

Madison is a city in Morgan County, Georgia, United States. It is part of the Atlanta-Athens-Clarke-Sandy Springs combined statistical area. The population was 4,447 at the 2020 census, up from 3,979 in 2010. The city is the county seat of Morgan County and the site of the Morgan County Courthouse.

Athens is a consolidated city-county in the U.S. state of Georgia. Downtown Athens lies about 70 miles (110 km) northeast of downtown Atlanta. The University of Georgia, the state's flagship public university and an R1 research institution, is in Athens and contributed to its initial growth. In 1991, after a vote the preceding year, the original City of Athens abandoned its charter to form a unified government with Clarke County, referred to jointly as Athens–Clarke County where it is the county seat.

Harriet Powers was an American folk artist and quilter born into slavery in rural northeast Georgia. Powers used traditional appliqué techniques to make quilts that expressed local legends, Bible stories, and astronomical events. Powers married young and had a large family. After the American Civil War and emancipation, she and her husband became landowners by the 1880s, but lost their land due to financial problems.

Rose Hill Cemetery is a 50-acre cemetery located on the banks of the Ocmulgee River in Macon, Georgia, United States, that opened in 1840. Simri Rose, a horticulturist and designer of the cemetery, was instrumental in the planning of the city of Macon and planned Rose Hill Cemetery in return for being able to choose his own burial plot. The cemetery is named in his honor.

The Prospect Hill Cemetery, located at 3202 Parker Street in the Prospect Hill neighborhood of North Omaha, Nebraska, United States, is believed to be the oldest pioneer cemetery in Omaha. It is between 31st and 33rd Streets and Parker and Grant Streets.

The Moore's Ford lynchings, also known as the 1946 Georgia lynching, refers to the July 25, 1946, murders of four young African Americans by a mob of white men. Tradition says that the murders were committed on Moore's Ford Bridge in Walton and Oconee counties between Monroe and Watkinsville, but the four victims, two married couples, were shot and killed on a nearby dirt road.

The Decatur Cemetery is a historic graveyard within the city of Decatur, Georgia, United States.

The Morton Theatre, located in downtown Athens, Georgia, at 195 West Washington Street, is one of the first vaudeville theatres in the United States uniquely built, owned, and operated by an African-American businessman: Monroe Morton. In 2001, its location was termed Athens' "Hot Corner". The Theatre currently operates as a rental facility that hosts a wide range of dramatic, musical, and dance performances as well as special events.

Jackson Street Cemetery, also known as Old Athens Cemetery, was the original cemetery for Athens, Georgia and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It was in official use as the town cemetery from about 1810 to 1856, until Oconee Hill Cemetery opened. The last known burial was in 1898.

Woodlawn Cemetery is a historic cemetery in the Benning Ridge neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States. The 22.5-acre (91,000 m2) cemetery contains approximately 36,000 burials, nearly all of them African Americans. The cemetery was added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 20, 1996.

Mount Zion Cemetery/Female Union Band Society Cemetery is a historic cemetery located at 27th Street NW and Mill Road NW in the Georgetown neighborhood of Washington, D.C., in the United States. The cemetery is actually two adjoining burial grounds: the Mount Zion Cemetery and Female Union Band Society Cemetery. Together these cemeteries occupy approximately three and a half acres of land. The property fronts Mill Road NW and overlooks Rock Creek Park to the rear. Mount Zion Cemetery, positioned to the East, is approximately 67,300 square feet in area; the Female Union Band Cemetery, situated to the West, contains approximately 66,500 square feet. Mount Zion Cemetery, founded in 1808 as The Old Methodist Burial Ground, was leased property later sold to Mount Zion United Methodist Church. Although the cemetery buried both White and Black persons since its inception, it served an almost exclusively African American population after 1849. In 1842, the Female Union Band Society purchased the western lot to establish a secular burying ground for African Americans. Both cemeteries were abandoned by 1950.

Athens Christian School (ACS) is a private, PreK–12 non-denominational Christian school located in Athens, Georgia, United States.

Columbian Harmony Cemetery was an African-American cemetery that formerly existed at 9th Street NE and Rhode Island Avenue NE in Washington, D.C., in the United States. Constructed in 1859, it was the successor to the smaller Harmoneon Cemetery in downtown Washington. All graves in the cemetery were moved to National Harmony Memorial Park in Landover, Maryland, in 1959. The cemetery site was sold to developers, and a portion used for the Rhode Island Avenue – Brentwood Washington Metro station.

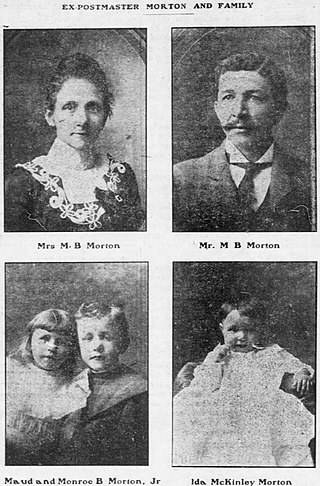

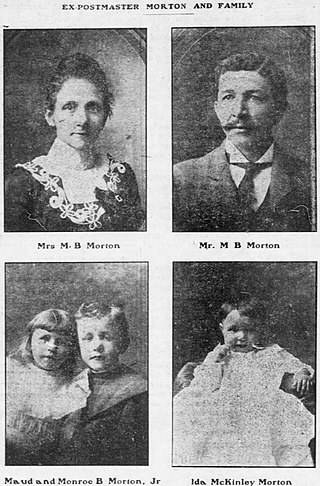

Monroe Bowers Morton, nicknamed Pink Morton was a prominent building owner, publisher, building contractor, developer, and postmaster in late 19th-century Georgia. An African American, he lived most of his life in Athens, Georgia, where he published a newspaper and built the Morton Building. The building included the Morton Theatre on its upper floors, a vaudeville venue, and offices for African-American professionals including doctors and druggists (pharmacists) on its ground floor. Occupants included Dr. Ida Mae Johnson Hiram, the first Black woman to be licensed to practice medicine (dentistry) in the state, and Dr. William H. Harris, one of the founders of the Georgia State Medical Association of Colored Physicians, Dentists and Druggists.

Madison "Mat" Davis was an American slave who became a member of the Georgia Assembly representing Clarke County, Georgia and the first African American postmaster in Athens, Georgia, after being emancipated. He was active in Republican Party politics.

Albert L. Hester was a professor of journalism at the University of Georgia (UGA), a columnist, historian, newspaper reporter, and author. He wrote more than ten books including Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery: An African-American Historical Site about the Gospel Pilgrim Cemetery for African Americans in Athens, Georgia, and Enduring Legacy: Clarke County, Georgia's Ex-Slave Legislators Madison Davis and Alfred Richardson about Madison Davis and Alfred Richardson. He wrote Athens, Georgia, Celebrating Two Hundred Years at the Millenium with his wife Conoly Hester, who is also a writer and editor. He also authored some 200 articles.

Alfred Richardson (1837?–1872) was a member of the Georgia Assembly in the U.S. State of Georgia, representing Clarke County. An African American, he entered government service after the U.S. Civil War during the Reconstruction era. Richardson faced hostility, intimidation, and physical attacks representing Clarke County. Richardson survived two shooting attacks by the Ku Klux Klan. In 1872 Richardson testified to a congressional committee that it was not safe for him to go home so he was staying in Athens, Georgia, and that many other "Colored" people had been forced to flee their farms in fear. He also spoke about being attacked and shot at at his house by men in disguise and said that he had been threatened, told of many instances of whippings, and that fellow "Colored" people were told that they should vote for Democrats or not vote at all.

William Anderson Pledger was a lawyer, newspaper publisher, and politician in Georgia. He is credited as the first African American lawyer in Atlanta and his political roles and efforts led the way for many who followed.