The hanbok is a traditional clothing of the Korean people. The term hanbok is primarily used by South Koreans; North Koreans refer to the clothes as chosŏn-ot. The clothes are also worn in the Korean diaspora, especially by Koreans in China.

Durumagi is a variety of po, or overcoat, in hanbok, the traditional Korean attire. It is a form of outerwear which is usually worn as the topmost layer of clothing, over a jeogori (jacket) and baji (pants). It also goes by the names jumagui, juchaui, or juui,

Zhiduo, also known as zhishen when it is decorated with outside pendulums, and haiqing, refers to two types of traditional changyi or paofu which were worn as outer robes by men in the broad sense; i.e. the casual zhiduo in Hanfu and the priests’ zhiduo, in the broad sense. As a specific term, the zhiduo refers to the former. The zhiduo was also called daopao by Wang Zhishen in the Ming dynasty although the daopao refers to another kind of paofu. Nowadays, the haiqing is sometimes referred as daopao. In present days Taiwan, the haiqing is also worn by the Zhenyi Taoist priests. The term "haiqing" can also be a specific term which refers to the long black or yellow robe worn by Buddhist monks.

A yuanlingshan is a type of round-collared upper garment in the traditional Chinese style of clothing known as Hanfu; it is also referred to as a yuanlingpao or a panlingpao when used as a robe. The yuanlingshan and yuanlingpao were both developed under the influence of ancient Chinese clothing, known as Hufu, originating from the Donghu people during the early Han dynasty and later by the Wuhu, including the Xianbei people, during the Six Dynasties period. The yuanlingpao is an article of formal attire primarily worn by men, although in certain dynasties, such as the Tang dynasty, it was also fashionable for women to wear. In the Tang dynasty, the yuanlingpao could be transformed into the fanlingpao using buttons.

Diyi, also called known as huiyi and miaofu, is the historical Chinese attire worn by the empresses of the Song dynasty and by the empresses and crown princesses in the Ming Dynasty. The diyi also had different names based on its colour, such as yudi, quedi, and weidi. It is a formal wear meant only for ceremonial purposes. It is a form of shenyi, and is embroidered with long-tail pheasants and circular flowers. It is worn with guan known as fengguan which is typically characterized by the absence of dangling string of pearls by the sides. It was first recorded as Huiyi in the Zhou dynasty.

Daxiushan, also referred as dianchailiyi, dashan, daxiu, is a form of shan, a traditional Chinese upper garment, with broad sleeves in Hanfu. It was most popular during the Tang dynasty, particularly among the members of royalty. The daxiushan was mainly worn for special ceremonial occasions and had different variations, mainly the result of different collar formations. The daxiushan could be worn under a skirt or as an outerwear. After the Tang dynasty, it continued to be worn in the Song and Ming dynasties.

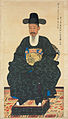

Myeonbok is a kind of ceremonial clothing worn by the kings of Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) in Korea. Myeonbok was adopted from Chinese Mianfu, and is worn by kings at special events such as the coronation, morning audience, Lunar New Year's audience, ancestral rites at Jongmyo and the soil and grain rite at Sajikdan. Myeonbok symbolizes the dignity of king when conducting important ceremonies.

Dragon robes, also known as gunlongpao or longpao for short, is a form of everyday clothing which had a Chinese dragon, called long (龍), as the main decoration; it was worn by the emperors of China. Dragon robes were also adopted by the rulers of neighbouring countries, such as Korea, Vietnam, and the Ryukyu Kingdom.

Hanfu are the traditional styles of clothing worn by the Han Chinese. There are several representative styles of hanfu, such as the ruqun, the aoqun, the beizi and the shenyi, and the shanku.

The Round collar robe, also called yuanlingpao and yuanlingshan in China, danryeong in Korea, was a style of paofu, a Chinese robe, worn in ancient China, which was long enough to cover the entire body of its wearer. The Chinese yuanlingpao was developed under the influences of the Hufu worn by the Donghu people and by the Wuhu. Depending on time period, the Chinese yuanlingpao also had some traces of influences from the Hufu worn by the Sogdian. The Chinese yuanlingpao continued to evolve, developing distinctive Chinese characteristics with time and lost its Hufu connotation. It eventually became fully integrated in the Hanfu system for the imperial and court dress attire. Under the influence of ancient China, the Chinese yuanlingpao was adopted by the rest of the East Asian cultural sphere.

Mianfu is a kind of Chinese clothing in hanfu; it was worn by emperors, kings, and princes, and in some instances by the nobles in historical China from the Shang to the Ming dynasty. The mianfu is the highest level of formal dress worn by Chinese monarchs and the ruling families in special ceremonial events such as coronation, morning audience, ancestral rites, worship, new year's audience and other ceremonial activities. There were various forms of mianfu, and the mianfu also had its own system of attire called the mianfu system which was developed back in the Western Zhou dynasty. The mianfu was used by every dynasty from Zhou dynasty onward until the collapse of the Ming dynasty. The Twelve Ornaments were used on the traditional imperial robes in China, including on the mianfu. These Twelve Ornaments were later adopted in clothing of other ethnic groups; for examples, the Khitan and the Jurchen rulers adopted the Twelve ornaments in 946 AD and in 1140 AD respectively. The Korean kings have also adopted clothing embellished with nine out of the Twelve ornaments since 1065 AD after the Liao emperor had bestowed a nine-symbol robe to the Korean king, King Munjong, in 1043 AD where it became known as gujangbok.

The fashion in the Yuan dynasty of Mongol (1271–1368) showed cultural diversity with the coexistence of various ethnic clothing, such as Mongol clothing, Han clothing and Korean clothing. The Mongol dress was the clothing of elite for both genders. Mongol attire worn in the 13th-14th century was different from the Han clothing from the Tang and Song dynasties. The Yuan dynasty court clothing also allowed the mixed of Mongol and Han style, and the official dress code of the Yuan dynasty also became a mixture of Han and Mongol clothing styles. After the founding of the Yuan dynasty, the Mongols strongly influenced the lifestyle and customs of the Han people.

Paofu, also known as pao for short, is a form of a long, one-piece robe in Hanfu, which is characterized by the natural integration of the upper and lower part of the robe which is cut from a single fabric. The term is often used to refer to the jiaolingpao and the yuanlingpao. The jiaolingpao was worn since the Zhou dynasty and became prominent in the Han dynasty. The jiaolingpao was a unisex, one-piece robe; while it was worn mainly by men, women could also wear it. It initially looked similar to the ancient shenyi; however, these two robes are structurally different from each other. With time, the ancient shenyi disappeared while the paofu evolved gaining different features in each succeeding dynasties; the paofu continues to be worn even in present day. The term paofu refers to the "long robe" worn by ancient Chinese, and can include several form of Chinese robes of various origins and cuts, including Changshan,Qipao, Shenyi,Tieli, Zhisun, Yesa.

Terlig, also known as tieli or bianxianao or Yaoxianao[zi] in Chinese, or commonly referred as Mongol dress or plait-line robe, is an archetypal type of Mongol clothing for men.

Xiapei, also known as hapi in Korea, is a type of Chinese clothing accessory in either the form of a long scarf, a neckband, or in the shape of waistcoat depending on the time period. It was also referred as xiapeizhui when it was ornamented with a peizhui at its front end; the peizhui ornament could be made of diverse materials, such as silver, jade, and gold.

Bixi, also known as fu, is generic term which refers to a type of traditional Chinese decorative piece of fabric, which acts as a knee covering, in Hanfu. The bixi originated in China where it originated from the primitive clothing of the ancient; since then, it continued to be worn by both men and women, and eventually became part of the Chinese ceremonial attire. The bixi was later introduced in Korea during Goryeo and Joseon by the Ming dynasty, along with many garments for royalties.

Dapho (Korean: 답호), also known as dapbok or dapo, is either a sleeveless or short sleeved garment, The dapo originated in the Yuan dynasty and was introduced in Korea during the late Goryeo. With time the structure of the dapho changed in shape structure although it maintained the same name. Some form of dapho was introduced from China's Ming dynasty in the form of dahu during the Joseon period, when the clothing was bestowed to various Joseon kings.

Xuanduan, also known as yuanduan, is a form of Chinese court dress which was made of dark or black fabric. It is a form of yichang. It was worn since the Western Zhou dynasty. During the Ming dynasty, under the reign of Emperor Jiajing, the xuanduan became a model for the regulations reforms related to yanfu worn by the Emperor and officials.

Daojiao fushi, also known as Taoist clothing, are religious clothing and adornment worn by devotees and practitioners of Taoism, an indigenous religion and life philosophy in China. Chinese culture attaches great importance to "cap and gown" are seen as important signs of levels of etiquettes; it is also a visible marker of the Taoist identity. Taoist ritual garments (sometimes referred as daoyi are forms of ritual clothing. These clothing worn by the Taoist priests are inherited from the Han Chinese traditional clothing and holds clear Taoist cultural meaning. When performing rituals and important rituals, Taoist priests wear ceremonial attires which appear to be aligned with elements of Chinese cosmology; these ceremonial attires are therefore strong spiritual intermediaries acting on the part of the Taoist devotees community. Different forms of clothing will be worn by Taoist priests in accordance to ritual types and obvious distinctions are found in the attire of Taoist priests based on their different positions to the altar. There were also codes which would stipulate the appropriate Taoist attire to be worn during both ritual performance and when being off duty.

Guan, literally translated as hat or cap or crown in English, is a general term which refers to a type of headwear in Hanfu which covers a small area of the upper part of the head instead of the entire head. The guan was typically a formal form of headwear which was worn together with its corresponding court dress attire. There were sumptuary laws which regulated the wearing of guan; however, these laws were not fixed; and thus, they would differ from dynasty to dynasty. There were various forms and types of guan.