Related Research Articles

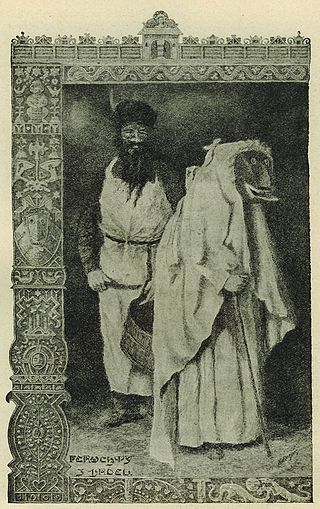

Perchta or Berchta, also commonly known as Percht and other variations, was once known as a goddess in Alpine paganism in the Upper German and Austrian regions of the Alps. Her name may mean "the bright one" and is probably related to the name Berchtentag, meaning the feast of the Epiphany. Eugen Mogk provides an alternative etymology, attributing the origin of the name Perchta to the Old High German verb pergan, meaning "hidden" or "covered".

"Frau Holle" is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm in Children's and Household Tales in 1812. It is of Aarne-Thompson type 480.

The moss people or moss folk, also referred to as the wood people or wood folk or forest folk, are a class of fairy folk, variously compared to dwarfs, elves, or spirits, described in German folklore as having an intimate connection to trees and the forest. In German, the words Schrat and Waldschrat are also used for a moss person. The diminutive Schrätlein also serves as synonym for a nightmare creature.

Knésetja is the Old Norse expression for a custom in Germanic law, by which adoption was formally expressed by setting the fosterchild on the knees of the foster-father.

The Schrat or Schratt, also Schraz or Waldschrat, is a rather diverse German legendary creature with aspects of either a wood sprite, domestic sprite and a nightmare demon.

The aufhocker or huckup is a shapeshifter in German folklore.

Getting lost is the occurrence of a person or animal losing spatial reference. This situation consists of two elements: the feeling of disorientation and a spatial component. While getting lost, being lost or totally lost, etc. are popular expressions for someone in a desperate situation, getting lost is also a positive term for a goal some travellers have in exploring without a plan. Getting lost can also occur in metaphorical senses, such as being unable to follow a conversation.

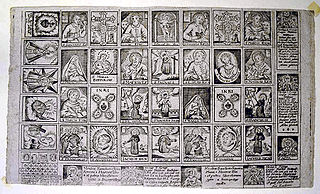

Schluckbildchen; from German, which means literally "swallowable pictures", are small notes of paper that have a sacred image on them with the purpose of being swallowed. They were used as a religious practice in the folk medicine throughout the eighteenth to twentieth century, and were believed to possess curative powers. Frequently found in the "spiritual medicine chests" of devout believers at that time, by swallowing them they wished to gain these curative powers. They are to be distinguished from Esszettel; from German, meaning "edible notes of paper", the latter only having text written on them.

The Buschgroßmutter is a legendary creature from German folklore, especially found in folktales from the regions Thuringia, Saxony, former German-speaking Silesia and the former German-speaking parts of Bohemia. She is called various regional names such as Pusch-Grohla and Buschmutter in Silesia, 's Buschkathel and Buschweibchen in Bohemia, Buschweiblein and Buschweibel in Silesia again. Buschweibchen, Buschweiblein, and Buschweibel all mean "shrub woman", with Weibchen, Weiblein or Weibel being the diminutive of Weib, "woman".

A Bieresel is a type of kobold of German folklore.

The Irrwurz, Irrwurzel or Irrkraut is a legendary plant from German-speaking countries. In France it is known as herbe d'égarement among other names.

The Niß Puk or Nis Puk is a legendary creature, a kind of Kobold, from Danish-, Low German- and North Frisian-speaking areas of areas of Northern Germany and Southern Denmark, among them Schleswig, today divided into the German Southern Schleswig and Danish Northern Schleswig. An earlier saying says Nissen does not want to go over the Eideren, i.e. not to Holstein to the South of Schleswig. Depending on the place, it can either appear as a domestic spirit or take on the role of a being generally called Drak or Kobold in Danish and German mythology, an infernal spirit making its owner wealthy by bringing them stolen goods.

The Uhaml is a spirit from German folktales. It was known among the former Germans of Bohemia and Silesia, now part of the Czech Republic and Poland respectively, particularly in the former Iglau language island of Bohemia. The Uhaml is an airy sprite, a ghost, or possibly some kind of demonic bird. Nothing is known about its appearance other than it having horse feet.

The Drak, Drâk, Dråk, Drakel or Fürdrak, in Oldenburg also Drake (f.), is a household spirit from German folklore often identified with the Kobold or the devil, both of which are also used as synonymous terms for Drak. Otherwise it is also known as Drache (dragon) but has nothing much to do with the reptilian monster in general.

The Klagmuhme or Klagemuhme is a female sprite from German folklore also known as Klagmutter or Klagemutter. She heralds imminent death through wailing and whining and is thus the German equivalent of the banshee.

The Fänggen are female wood sprites in German folklore exclusively found in Tyrol.

The witte Wiwer, witte Wîwer, witte Wiewer or witte Wiver are legendary creatures from German folklore similar to but distinct from the weiße Frauen. Other names are unterirdische Weiber in Mecklenburg and Sibyllen in Northwestern Germany.

The Feuermann, also Brennender, Brünnling, Brünnlinger, Brünnlig, brünnigs Mannli, Züsler, and Glühender is a fiery ghost from German folklore different from the will-o'-the-wisp, the main difference being its size: Feuermänner are rather big, Irrlichter rather small. An often recurring term for Feuermänner is that of glühende Männer.

The Hemann, also Homann, Hoymann, Hoimann, or Jochhoimann,, is a spirit from German folklore known to scare people through yelling, usually invisibly and at night. The first part of its name usually depicts the kind of yell heard from the Hemann. It can be found in former German-speaking Bohemia, former German-speaking Silesia, Upper Palatinate, the Fichtel Mountains, the Vogtland, Westphalia, and around Crailsheim in Baden-Württemberg.

The Gütel is a variant of and synonym for the Kobold in German folklore. Originating in the Middle High German term gütelgüttel signifying an idol, the name was later connected with the adjective gut = good.

References

- ↑ Riegler: Grille. In: Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli, Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer: Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens: Band 3 Freen-Hexenschuss. Berlin/New York 2000, p. 1162.

- 1 2 Riegler: Grille. In: Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli, Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer: Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens: Band 3 Freen-Hexenschuss. Berlin/New York 2000, p. 1166.

- ↑ Eckstein: Semmel. In: Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli, Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer: Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens: Band 7 Pflügen-Signatur. Berlin/New York 2000, p. 1638.

- ↑ Riegler: Grille. In: Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli, Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer: Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens: Band 3 Freen-Hexenschuss. Berlin/New York 2000, p. 1162 f.

- ↑ Ludwig Bechstein: Die goldene Schäferei. In: Ingeborg Haun, Jacob Grimm, Wilhelm Grimm, Hans Christian Andersen, Ludwig Bechstein, Wilhelm Hauff: Die schönsten Märchen. Unknown year and place, p. 295 ff., 301 ff.

- 1 2 3 Riegler: Grille. In: Hanns Bächtold-Stäubli, Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer: Handwörterbuch des Deutschen Aberglaubens: Band 3 Freen-Hexenschuss. Berlin/New York 2000, p. 1163.

- ↑ Ludwig Bechstein: Deutsches Sagenbuch. Meersbusch, Leipzig 1930, p. 377.

- ↑ Ludwig Bechstein: Deutsches Sagenbuch. Meersbusch, Leipzig 1930, p. 377 f.

- ↑ Ludwig Bechstein: Thüringer Sagenbuch: Band 2. Bad Langensalza 2014, p. 107.