The Schrat or Schratt, also Schraz [1] or Waldschrat (forest Schrat), [2] is a rather diverse German and Slavic legendary creature with aspects of either a wood sprite, domestic sprite and a nightmare demon. [1]

The Schrat or Schratt, also Schraz [1] or Waldschrat (forest Schrat), [2] is a rather diverse German and Slavic legendary creature with aspects of either a wood sprite, domestic sprite and a nightmare demon. [1]

The word Schrat originates in the same Germanic word root as Old Norse skrati, skratti (sorcerer, giant), Icelandic skratti (devil) and vatnskratti (water sprite), Swedish skratte (fool, sorcerer, devil), and English scrat (devil). [3]

The German term entered Slavic languages and (via North Germanic languages) Finno-Ugric ones as well. Examples are Polish skrzat, skrzot (domestic sprite, dwarf), Czech škrat, škrátek, škrítek (domestic sprite, gold bringing devil), Slovene škrat, škratek, škratelj (domestic sprite, mining sprite), and škratec (whirlwind, Polish plait) as well as Estonian krat (domestic sprite, Drak). [4]

The Schrat is first attested in Medieval sources. Old High German sources have scrato, [5] scrat, [2] scraz, scraaz, skrez, [1] screiz, waltscrate (walt = forest), screzzolscratto, sklezzo, slezzo, and sletto (pl. scrazza, screzza, screza, waltscraze, waltsraze). [3]

Middle High German sources give the forms schrat, schrate, [5] waltschrate, [3] waltschrat, [2] schretel, schretelîn, [1] schretlin, [2] schretlein, [6] schraz, schrawaz, schreczl, [1] schreczlein, [6] schreczlîn [1] or schreczlin, [6] and waltscherekken (forest terror; also the pl. schletzen). [3]

In Old High German sources, the word is used to translate the Latin terms referring to wood sprites and nightmare demons, such as pilosi (hairy sprites), fauni (fauns), satiri, (satyrs), silvestres homines (forest humans), incubus , incubator, and larva (spirit of the dead). [7] Accordingly, the earliest known Schrat was likely a furry or hairy fiend [5] or an anthropomorphic or theriomorphic spirit dwelling in the woods and causing nightmares. [8]

Middle High German sources continue to translate satyrus and incubus as Schrat, indicating it as a wood sprite and nightmare demon, but further use the term to translate penates too, denoting the Schrat as domestic sprite. [6]

The Waldschrat is a solitary wood sprite looking scraggily, shaggily, partially like an animal, with eyebrows grown together, and wolf teeth in its mouth. [2]

The Austrian Schrat or Waldkobold (pl. Schratln) looks like described above, is small and usually solitary. The Schratln love the deep, dark forest and will move away if the forest is logged. The Schrat likes to play malicious pranks and tease evilly. If offended, it breaks the woodcutters' axes in two and lets trees fall in the wrong direction. [9]

In the Swiss valley Muotatal, before 1638 there was an Epiphany procession called Greifflete associated with two female wood sprites, Strudeli and Strätteli, the latter being a derivative of Schrat. [5]

In Southern Germany and Switzerland, especially in regions with Alemannic dialect, the Schrat is rather an Alp , a nightmare demon. [10] As such it is rather known under diminutive names such as Schrätlein, Schrättlein, [1] Schrättele, [10] Schrätele, Schrätel, Schrattl, Schrattel,Schratel, Schrättlig, [10] Schrättling, [1] Schrattele, Schrettele, [11] Schrötele, Schröttele, Schröttlich, Schreitel, [1] Schrätzel, [10] Schrätzlein, [1] Schrecksel, [10] Schrecksele [1] and Schreckle [10] (corrupted forms based on German Schreck = fear or fright), Scherzel (a corrupted form reminiscent of German Scherz = jest), Schrätzmännel (sg., pl.; ‚Schrat manikin), Strädel, [10] Schlaarzla, Schrähelein, [1] Rettele, Rätzel, Ritzel, [10] Letzel, and Letzekäppel (Käppel = little cap), [1] Drückerle (presser), and Nachtmännle (night manikin). [11] In Baden, the Schrättele enters by crawling through the keyhole and sits on the sleeper's chest. [12] It enters and exits through the keyhole in Swabia as well. [11] It can also enter through the window as a black hen. [13]

Often, the nightmare demon Schrat is in truth a living human. This Schrättlich or Schrätelhexe (Schrat witch) can easily be identified due to their characteristic of eyebrows grown together, the so-called Räzel. [14]

In Swabia, the Schratt is a woman suffering from an hereditary ailment known as schrättleweis gehen or Schrattweisgehen (both: going in the manner of a Schrat) which is an affliction usually inherited from one's mother. The afflicted person will have to step out every night at midnight, i.e. the body will lie around as if dead but the soul will have left it in the shape of a white mouse. The Schratt is impelled to "press" (German drücken) something or someone, be it human, cattle, or tree. The nightly Drücken is very exhausting, making the Schratt ill. Only one thing can free the Schratt from her condition. She must be allowed to press the best horse in the stable to death. [15]

According to other Swabian belief, the nightmare-bringing Schrat is a child died unbaptized. In Baden, it is a deceased relative of the nightmare victim. [16]

In Tyrol, however, it is believed that the Trud is the nightmare demon of humans while the Schrattl or Schrattel torments the cattle. [17]

In Switzerland, the Schrättlig sucks the udders of cows and goats dry and makes horses become schretig, i.e. fall ill. [18] In Swabia, the Schrettele also sucks human breasts and animal udders until they swell, tangles horse manes, and makes Polish plaits. [11] In Austria, The Schrat tangles horse tails and dishevels horse manes. [19]

The Schrat is further known to cause illnesses by shooting arrows. Its arrow is the belemnite (called Schrattenstein, Schrat stone) which is also used to ward it off. [20] Beside the Schrattenstein, it also fears the pentagram (called Schrattlesfuß, Schrat foot in Swabia) and stones of the same name with dinosaur footprints. [11] The Schrätteli can be exterminated by burning the bone whose appearance it takes when morning comes. [21] The same is true for burning the straw caught at night, for in the morning it will become a woman covered with burns and never return again. If it is cut with a Schreckselesmesser (Schrat knife), a knife with three crosses on its blade, the Schrettele will also never return again. [22] The Schrat can further be kept out of stables by placing a Schratlgatter (Schrat fence) above the stable door. This is an object made from five kinds of wood looking like an H written inside an X. A convex mirror called Schratspiegel (Schrat mirror) also works the same way. [19]

In Southeastern Germany and Austria, the Schrat is still more akin to a domestic Kobold , only occasionally appearing as an incubus. [23] The Schrat as domestic sprite is particularly known in Bavaria, the Vogtland, Upper Palatinate, the Fichtel Mountains, Styria, and Carinthia. [6]

In Styria and Carinthia, the Schratl dwells inside the stove, expecting to be given millet gruel for its services. [24] In Styria, this stove or oven (called Schratlofen; Schrat stove) might also be a solitary rock formation or rock hole rather than a true stove. [25] In Carinthia, the Schratl can be intentionally driven away by gifting it clothes. [26]

According to belief from the 15th century, every house has a schreczlein which, if honored by the inhabitants of the house, gives its human owners property and honor. [6] Accordingly, the schretlein or trut (i.e. Trud) was gifted little red shoes which was a sin according to Medieval clergy. [27]

In Carinthia, the Schratelmannel (Schrat manikin) knocks in the bedroom walls at night like a Kobold or rather poltergeist. [20]

Also in Carinthia, the Schratt appears as the play of the sun rays on the wall, as a blue flamelet, or as a red face looking out of the cellar window. [6] When summoned, it sits down on the doorstep. [28]

The Schretel takes on the appearance of a butterfly in Tyrol and the Sarganserland of the Canton of St. Gallen, in the latter also of a magpie, fox, or black cat. [29] Near Radenstein in Carinthia, the caterpillar is called and thus identified as Schratel. [30] The butterfly is sometimes called schrätteli, schrâtl, schràttele or schrèttele and accordingly identified [31] with the nightmare demon Schrätteli. [32]

The Alsatian Schrätzmännel also appear as dwarves (German Zwerge, sg. Zwerg) dwelling in caves in the woods and mountains. [6]

The same is true for the Razeln or Schrazeln in Upper Palatinate, whose cave dwellings are known as Razellöcher (Schrat holes). [6] Other names for them are Razen, Schrazen, Strazeln, Straseln, and Schraseln. They dwell in the mountains and help the humans with their work, acting as domestic sprites. This they do at night, for they dislike to be seen. They only enter the homes of good people and bring good fortune upon them, expecting but the food left over on the dishes as their payment. Any other form of gratitude, especially gifts, will drive them away instead, for they will think their service has been terminated, and they will leave with tears. First they wort, then they eat, and after that they go into the baking oven for dancing and threshing. Ten pairs or at least twelve Razen are said to fit inside an oven for threshing. [33]

A red secretion left behind at trees by butterflies is said to be the blood of the Schrätlein or Schretlein who are wounded and chased by the devil (German Teufel). [34] [31] Conversely, the Schrat can also be identified as the devil itself. [16]

Schrättlig is a synonym for witch (German Hexe). [35] In Tyrol and the Sarganserland, the Schrättlig also is thought to be the soul of a deceased evildoer living among people as an ordinary human, particularly an old woman. It is able to take on animal appearance, and often harms humans, animals and plants, further causes storm and tempest, but can also become a luck-bringing domestic sprite identified with lares and penates. [36]

The Schrat might also show behavior similar to the devil or witches. In Carinthia, whenever somebody wants to hang oneself, then a Schratt will come and nod in approval. [37] The Schrat travels in the whirlwind as well, hence the whirlwind is known as Schretel or schrádl in Bavaria and the Burgenland respectively. [38]

In Bavaria, and Tyrol, the souls of unbaptized children forming the retinue of Stempe (i.e. Perchta ) are called Schrätlein. Like Perchta, the schretelen were offered food on Epiphany Day in 15th century Bavaria. [39]

Among the Yiddish-speaking Jews of Eastern Europe, there is belief in the shrettele [40] (pl. shretelekh [41] ) which they might have brought with them when they came from Alsace and Southern Germany. [40]

The shretele is very kind. [40] It is described as a small elflike creature, more specifically a tiny, handsome, raggedly dressed little man. Shretelekh can be found in human homes where they like to help out, e.g. by completing shoes overnight in a shoemaker's home. If given tiny suits in gratitude, they will stop working and sing that they look too glorious for work, dancing out of the house but leaving good fortune behind. [42]

The shretele might also stretch out a tiny hand from the chimney corner, asking for food. If given e.g. some crackling, it will make the kitchen work successful. For example, if pouring goose fat from a frying pan into containers, one might be able to do so for hours, filling all containers in the house without emptying the pan – until someone cusses about this. Cussing will drive the shretele away. [43]

The shretele might also dwell under the bed. From there it might come out to rock the baby's cradle, give the baby a light slap to make it stop crying, or nip from a brandy bottle. A bottle from which a shretele has sipped will always remain full no matter how much is poured out. [44]

In Yiddish folklore, the function of the nightmare demon belongs to another kind of legendary creature, the kapelyushnikl (Polish for hat maker; [40] pl. kapelyushniklekh [45] ) is a hat-wearing little being bent on pestering and teasing horses. It can only be found in Slavic countries and might even be an original East European Jewish creation. [40]

The kapelyushniklekh can appear as a male and female pair of tiny beings wearing little caps, the woman also having braided hair tied with pretty ribbons. [45]

They love to ride horses all night, many kapelyushniklekh sitting on one horse, rendering the animal exhausted and sweating. Kapelyushniklekh prefer gray horses in particular. If one manages to snatch a cap from a kapelyushnikl, they will be driven away for good. Only the one who lost its cap will return promising a great deal of gold which, seen at daylight, will turn out to be a pile of rocks instead. [46]

They can also milk cows dry at night and steal the milk, but if caught and beaten they promise that, if spared, they will never return and that the amount of milk given by the cows will be double of what it originally used to be, which will come true. [45]

"Frau Holle" is a German fairy tale collected by the Brothers Grimm in Children's and Household Tales in 1812. It is of Aarne-Thompson type 480.

In German folklore, a nachzehrer is a type of wiedergänger (revenant) which was believed to be able to drag the living after it into death, either through malice or through the desire to be closer to its loved ones through various means. The word nachzehrer came to use in the nineteenth century, though belief in the creature the label is applied to precedes this by several centuries. The nachzehrer was prominent in the folklore of the northern regions of Germany, but even in Silesia and Bavaria, and the word was also used to describe a similar creature of the Kashubes of Northern Poland. The nachzehrer was similar to the Slavic vampire in that it was known to be a recently deceased person who returned from the grave to attack family and village acquaintances.

Knésetja is the Old Norse expression for a custom in Germanic law, by which adoption was formally expressed by setting the fosterchild on the knees of the foster-father.

Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer (1864–1936) was a Swiss folklorist, Germanist and medievalist, from 1900 professor for phonetics, Swiss dialectology and folklore at the University of Basle and founder of the Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Volkskunde in 1896. His 1902 essay Die Volkskunde als Wissenschaft received international attention.

The aufhocker or huckup is a shapeshifter in German folklore.

Getting lost is the occurrence of a person or animal losing spatial reference. This situation consists of two elements: the feeling of disorientation and a spatial component. While getting lost, being lost or totally lost, etc. are popular expressions for someone in a desperate situation, getting lost is also a positive term for a goal some travellers have in exploring without a plan. Getting lost can also occur in metaphorical senses, such as being unable to follow a conversation.

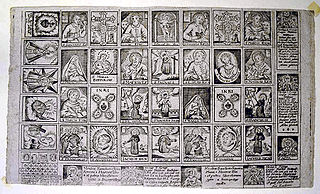

Schluckbildchen; from German, which means literally "swallowable pictures", are small notes of paper that have a sacred image on them with the purpose of being swallowed. They were used as a religious practice in the folk medicine throughout the eighteenth to twentieth century, and were believed to possess curative powers. Frequently found in the "spiritual medicine chests" of devout believers at that time, by swallowing them they wished to gain these curative powers. They are to be distinguished from Esszettel; from German, meaning "edible notes of paper", the latter only having text written on them.

The Buschgroßmutter is a legendary creature from German folklore, especially found in folktales from the regions Thuringia, Saxony, former German-speaking Silesia and the former German-speaking parts of Bohemia. She is called various regional names such as Pusch-Grohla and Buschmutter in Silesia, 's Buschkathel and Buschweibchen in Bohemia, Buschweiblein and Buschweibel in Silesia again. Buschweibchen, Buschweiblein, and Buschweibel all mean "shrub woman", with Weibchen, Weiblein or Weibel being the diminutive of Weib, "woman".

A Bieresel is a type of kobold of German folklore.

The Irrwurz, Irrwurzel or Irrkraut is a legendary plant from German-speaking countries. In France it is known as herbe d'égarement among other names.

The Nis Puk (sometimes also Niß Puk, in Danish also Nis Pug(e)) is a legendary creature, a kind of Kobold, from Danish-, Low German- and North Frisian-speaking areas of Northern Germany and Southern Denmark, among them Schleswig, today divided into the German Southern Schleswig and Danish Northern Schleswig. An earlier saying says Nissen does not want to go over the Eideren, i.e. not to Holstein to the South of Schleswig. Depending on the place, it can either appear as a domestic spirit or take on the role of a being generally called Drak or Kobold in Danish and German mythology, an infernal spirit making its owner wealthy by bringing them stolen goods.

The Uhaml is a spirit from German folktales. It was known among the former Germans of Bohemia and Silesia, now part of the Czech Republic and Poland respectively, particularly in the former Iglau language island of Bohemia. The Uhaml is an airy sprite, a ghost, or possibly some kind of demonic bird. Nothing is known about its appearance other than it having horse feet.

The Drak, Drâk, Dråk, Drakel or Fürdrak, in Oldenburg also Drake (f.), is a household spirit from German folklore often identified with the Kobold or the devil, both of which are also used as synonymous terms for Drak. Otherwise it is also known as Drache (dragon) but has nothing much to do with the reptilian monster in general.

The Klagmuhme or Klagemuhme is a female sprite from German folklore also known as Klagmutter or Klagemutter. She heralds imminent death through wailing and whining and is thus the German equivalent of the banshee.

The Fänggen are female wood sprites in German folklore exclusively found in Tyrol.

The witte Wiwer, witte Wîwer, witte Wiewer or witte Wiver are legendary creatures from (Low) German folklore similar to but distinct from the weiße Frauen. Other names are unterirdische Weiber in Mecklenburg and Sibyllen in Northwestern Germany.

The Heimchen is a being from German folklore with several related meanings.

The Feuermann, also Brennender, Brünnling, Brünnlinger, Brünnlig, brünnigs Mannli, Züsler, and Glühender is a fiery ghost from German folklore different from the will-o'-the-wisp, the main difference being its size: Feuermänner are rather big, Irrlichter rather small. An often recurring term for Feuermänner is that of glühende Männer.

The Hemann, also Homann, Hoymann, Hoimann, or Jochhoimann,, is a spirit from German folklore known to scare people through yelling, usually invisibly and at night. The first part of its name usually depicts the kind of yell heard from the Hemann. It can be found in former German-speaking Bohemia, former German-speaking Silesia, Upper Palatinate, the Fichtel Mountains, the Vogtland, Westphalia, and around Crailsheim in Baden-Württemberg.

The Gütel is a variant of and synonym for the Kobold in German folklore. Originating in the Middle High German term gütelgüttel signifying an idol, the name was later connected with the adjective gut = good.