Andreas Wistuba is a German taxonomist and botanist specialising in the carnivorous plant genera Heliamphora and Nepenthes. More than half of all known Heliamphora species have been described by Wistuba.

Dr. Joachim Nerz is a German taxonomist and botanist specialising in the carnivorous plant genera Heliamphora and Nepenthes. Nerz has described several new species, mostly with Andreas Wistuba.

Heliamphora chimantensis is a species of marsh pitcher plant endemic to the Chimantá Massif in Venezuela. Specifically, it has been recorded from Apacará and Chimantá Tepuis. It is thought to be more closely related to the southern growing H. tatei and H. neblinae than to any of the other species found in the Gran Sabana and its tepuis. All other species known from this region have between 10 and 15 anthers, while H. tatei, H. neblinae and H. chimantensis have around 20. However, the anthers of H. tatei and the closely related H. neblinae are 7–9 mm long, while those of H. chimantensis only reach 5 mm in length.

Heliamphora folliculata is a species of Marsh Pitcher Plant endemic to the Aparaman group of tepuis in Venezuela. It grows on all four mountains: Aparaman Tepui, Murosipan Tepui, Tereke Tepui and Kamakeiwaran Tepui.

Heliamphora glabra is a species of marsh pitcher plant native to Serra do Sol in Venezuela. It was for a long time considered a form of H. heterodoxa, but has recently been raised to species rank.

Heliamphora heterodoxa is a species of marsh pitcher plant native to Venezuela and adjacent Guyana. It was first discovered in 1944 on the slopes interlinking Ptari-tepui and Sororopan-tepui and formally described in 1951.

Heliamphora hispida is a species of Marsh Pitcher Plant endemic to Cerro Neblina, the southernmost tepui of the Guiana Highlands at the Brazil-Venezuela border.

Heliamphora ionasi is a species of marsh pitcher plant thought to be endemic to the plateau that lies between the bases of Ilu Tepui and Tramen Tepui in Venezuela. It produces the largest pitchers in the genus, which can be up to 50 cm in height.

Heliamphora minor is a species of marsh pitcher plant endemic to Auyán-tepui in Venezuela. As the name suggests, it is one of the smallest species in the genus. It is closely related to H. ciliata and H. pulchella.

Heliamphora neblinae is a species of marsh pitcher plant endemic to Cerro de la Neblina, Cerro Aracamuni and Cerro Avispa in Venezuela. It is one of the most variable species in the genus and was once considered to be a variety of H. tatei. It is unclear whether or not there is a consensus regarding its status as a species, with at least a few researchers supporting the taxonomic revision that would elevate both H. tatei var. neblinae and H. tatei f. macdonaldae to full species status.

Heliamphora nutans is a species of marsh pitcher plant native to the border area between Venezuela, Brazil and Guyana, where it grows on several tepuis, including Roraima, Kukenán, Yuruaní, Maringma, and Wei Assipu. Heliamphora nutans was the first Heliamphora to be described and is the best known species.

Heliamphora pulchella is a species of marsh pitcher plant endemic to the Chimanta Massif and surrounding tepuis in Venezuela. It is one of the smallest species and closely related to H. minor.

Heliamphora sarracenioides is a species of marsh pitcher plant endemic to Ptari Tepui in Bolívar state, Venezuela. Approximately 200 mature plants were observed in the type locality, however this site's true location and information regarding sympatric species has not been disclosed for conservation reasons. The species differentiates itself from others by the extremely wide pitcher lid, which resembles Sarracenia species. It is closest to H. heterodoxa and H. folliculata, from which it can be distinguished by the large lid glands and width of the pitcher lid.

Heliamphora tatei is a species of marsh pitcher plant endemic to Cerro Duida, Cerro Huachamacari and Cerro Marahuaca in Venezuela. It is closely related to H. macdonaldae, H. neblinae, and H. parva, and all three have in the past been considered forms or varieties of H. tatei. Like H. tatei, these species are noted for their stem-forming growth habit.

Heliamphora exappendiculata is a species of marsh pitcher plant native to the Chimantá and Aprada Massifs of Bolívar state, Venezuela. It was for a long time considered a variety of H. heterodoxa, but has recently been raised to species rank. Pitchers collect insects on flattened pitcher mouths which function as 'landing platforms' upon which prey falls from surrounding vegetation. Also, the pitcher shape effectively collects leaf litter and organic debris which may serve as additional source of nutrition for plants, similarly to H. ionasi.H. exappendiculata hybridizes naturally with H. pulchella and H. huberi in areas within which they grow together. This species occurs in shaded conditions, apparently preferring them over other habitats. In addition, plants upon Chimanta and Amuri Tepui grow directly upon the walls of gorges and ravines where surfaces are permanently wet. In contrast to those populations, on all other tepuis and massif regions the species grows on summit savannahs and stunted or shrubby forests, though these individuals represent a minority in habitat choice.

Heliamphora uncinata is a species of Marsh Pitcher Plant endemic to Venezuela. This species of carnivorous plant is known as a pitcher plant. Individuals use tube like leaves to trap insects that slip into the bottom. At the bottom of the "pitcher" there are digestive juices which slowly digest the prey item to give the plant additional nutrients. The pitchers of this species are around 25–35 cm long, and are 8–10 cm wide at the opening. The pitcher mouth is circular in shape and the back is raised to form the lid. It is known only from the type collection, which was made in a narrow canyon on Amurí-tepui. There it grows at an elevation of approximately 1850 m on sandstone cliff faces in shady conditions. It is also found in humus pockets and cracks at this location. The only other species in the genus known to have a similar growth habit is H. exappendiculata. These two taxa also share a number of morphological features and appear to be closely related. These shared morphological features include: the shape of pitchers, the general growth pattern, and appearance of nectaries.

Heliamphora huberi is a species of Marsh Pitcher Plant endemic to the Chimantá Massif in Venezuela, where it grows at elevations of 1850–2200 m in a variety of habitats. It has thus far been recorded from Angasima-tepui, Apacará-tepui, Amurí-tepui, Acopán-tepui, and the border of Torono- and Chimantá-tepui. Due to its intermediate appearance between species related to H. minor and H. heterodoxa, it is suspected to be of hybridogenic origin.

Heliamphora arenicola is a species of marsh pitcher plant known only from the western side of the Ilu–Tramen Massif in Venezuela's Gran Sabana, where it grows at elevations of less than 2000 m. It may also occur on Karaurin Tepui.

Heliamphora purpurascens is a species of marsh pitcher plant known only from the summit area of Ptari Tepui in Venezuela, where it grows at elevations of 2400–2500 m.

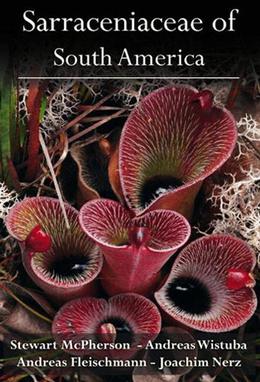

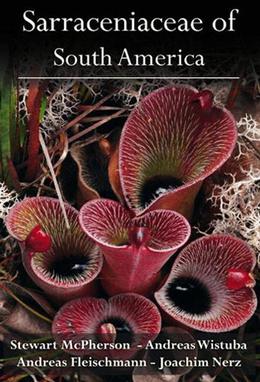

Sarraceniaceae of South America is a monograph on the pitcher plants of the genus Heliamphora by Stewart McPherson, Andreas Wistuba, Andreas Fleischmann, and Joachim Nerz. It was published in September 2011 by Redfern Natural History Productions and covered all species known at the time.