Related Research Articles

Edward Teach, better known as Blackbeard, was an English pirate who operated around the West Indies and the eastern coast of Britain's North American colonies. Little is known about his early life, but he may have been a sailor on privateer ships during Queen Anne's War before he settled on the Bahamian island of New Providence, a base for Captain Benjamin Hornigold, whose crew Teach joined around 1716. Hornigold placed him in command of a sloop that he had captured, and the two engaged in numerous acts of piracy. Their numbers were boosted by the addition to their fleet of two more ships, one of which was commanded by Stede Bonnet; but Hornigold retired from piracy toward the end of 1717, taking two vessels with him.

Bartholomew Roberts, born John Roberts, was a Welsh pirate and the most successful pirate of the Golden Age of Piracy, taking over 400 prizes in his career. Roberts raided ships off the Americas and the West African coast between 1719 and 1722; he is also noted for creating his own Pirate Code, and adopting an early variant of the Skull and Crossbones flag.

Captain Benjamin Hornigold (1680–1719) was an English pirate who operated during the tail end of the Golden Age of Piracy.

Robert Culliford was a pirate from Cornwall who is best remembered for repeatedly checking the designs of Captain William Kidd.

Woodes Rogers was an English sea captain, privateer, slave trader and, from 1718, the first Royal Governor of the Bahamas. He is known as the captain of the vessel that rescued marooned Alexander Selkirk, whose plight is generally believed to have inspired Daniel Defoe's Robinson Crusoe.

Henry Every, also known as Henry Avery, sometimes erroneously given as Jack Avery or John Avery, was an English pirate who operated in the Atlantic and Indian oceans in the mid-1690s. He probably used several aliases throughout his career, including Benjamin Bridgeman, and was known as Long Ben to his crewmen and associates.

Thomas Anstis was an early 18th-century pirate, who served under Captain Howell Davis and Captain Bartholomew Roberts, before setting up on his own account, raiding shipping on the eastern coast of the American colonies and in the Caribbean during what is often referred to as the "Golden Age of Piracy".

Charles Vane was an English pirate who operated in the Bahamas during the end of the Golden Age of Piracy.

Jeremiah Cocklyn, better known by the name Thomas Cocklyn, was an English pirate known primarily for his association with Howell Davis, Olivier Levasseur, Richard Taylor, and William Moody.

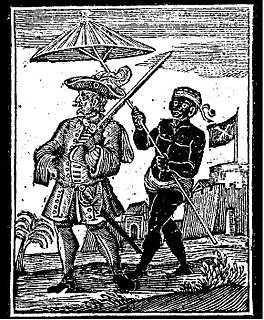

Caesar, later known as “Black Caesar”, was a pirate who operated during the Golden Age of Piracy. He served aboard the Queen Anne's Revenge of Edward Teach (Blackbeard) and was one of the surviving members of that crew following Blackbeard’s death at the hands of Lieutenant Robert Maynard in 1718. Myths surrounding his life - that he was African royalty and terrorized the Florida Keys for years before joining Blackbeard - have been intermixed with legends and fictional accounts as well as with other pirates.

Abraham Samuel, also known as "Tolinar Rex," born in Martinique, was a mulatto pirate of the Indian Ocean in the days of the Pirate Round in the late-1690s. Being shipwrecked on his way back to New York, he briefly led a combined pirate-Antanosy kingdom from Fort Dauphin, Madagascar, from 1697 until he died there in 1705.

Piracy was a phenomenon that was not limited to the Caribbean region. Golden Age pirates roamed off the coast of North America, Africa and the Caribbean.

The Flying Gang was an 18th-century group of pirates who established themselves in Nassau, New Providence in The Bahamas after the destruction of Port Royal in Jamaica. The gang consisted of the most notorious and cunning pirates of the time, buccaneers who terrorized and pillaged the Caribbean until the Royal Navy and infighting brought them to justice. They achieved great fame and wealth by raiding salvagers attempting to recover gold from the sunken Spanish treasure fleet. They established their own codes and governed themselves independent from any of the colonial powers of the time. Nassau was deemed the Republic of Pirates as it attracted many former privateers looking for work to its shores. The Governor of Bermuda stated that there were over 1000 pirates in Nassau at that time and that they outnumbered the mere hundred inhabitants in the town.

William Moody was a London-born pirate active in the Caribbean and off the coast of Africa. He is best known for his association with Olivier Levasseur and Thomas Cocklyn, crewmembers who succeeded him as captains in their own right.

Captain Grinnaway was a pirate from Bermuda, best known for being briefly and indirectly involved with Edward Teach.

Lewis Ferdinando was a pirate active near Bermuda during the Golden Age of Piracy.

Evan Jones was a Welsh-born pirate from New York active in the Indian Ocean, best known for his indirect connection to Robert Culliford and for capturing a future Mayor of New York.

Richard Tookerman was born on 16 May 1691 in Devon, Cornwall, England. He was the son of Josias Tookerman, a clergyman, and younger brother of Josias Tookerman II, a clergyman sent by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG) to Jamaica. He married Katherine Grant, widow of John Grant of Charleston, South Carolina by 1717. As a pirate, smuggler, and trader active in the Caribbean and the Carolinas, he became best known for involvement with pirates Stede Bonnet and Bartholomew Roberts.

Don Benito was a Spanish pirate and guarda costa privateer active in the Caribbean.

David Williams was a Welsh sailor who turned pirate after being abandoned on Madagascar. He was only briefly a captain, and is best known for sailing under a number of more prominent pirate captains.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Headlam, Cecil (1910). Calendar of State Papers Colonial, America and West Indies | British History Online (Vol18 ed.). London: His Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. vii-716. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- 1 2 Browne, William Hand (1905). Archives of Maryland, Volume 25. Baltimore MD: Maryland Historical Society. pp. 94–100, 587–588. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Donnelly, Mark P.; Diehl, Daniel (2012). Pirates of Virginia: Plunder and High Adventure on the Old Dominion Coastline. Mechanicsburg PA: Stackpole Books. pp. 66–67. ISBN 9780811745833 . Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- 1 2 Morriss, Margaret Shove (1914). Colonial Trade of Maryland, 1689-1715. Baltimore MD: Johns Hopkins Press. pp. 80-131. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Archives, The National. "The Discovery Service". discovery.nationalarchives.gov.uk. Retrieved 15 May 2018.