Baltimore is a village in western County Cork, Ireland. It is the main village in the parish of Rathmore and the Islands, the southernmost parish in Ireland. It is the main ferry port to Sherkin Island, Cape Clear Island and the eastern side of Roaring Water Bay and Carbery's Hundred Isles.

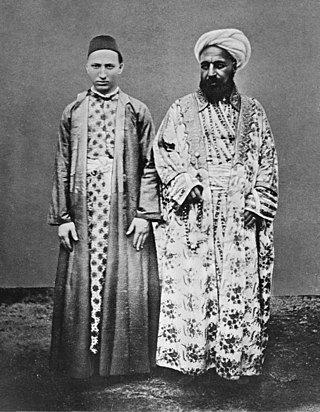

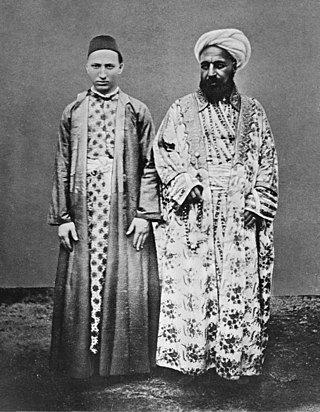

The Barbary pirates, Barbary corsairs, Ottoman corsairs, or naval mujahideen were mainly Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from the largely independent Barbary states. This area was known in Europe as the Barbary Coast, in reference to the Berbers. Slaves in Barbary could be of many ethnicities, and of many different religions, such as Christian, Jewish, or Muslim. Their predation extended throughout the Mediterranean, south along West Africa's Atlantic seaboard and into the North Atlantic as far north as Iceland, but they primarily operated in the western Mediterranean. In addition to seizing merchant ships, they engaged in razzias, raids on European coastal towns and villages, mainly in Italy, France, Spain, and Portugal, but also in the British Isles, and Iceland.

White slavery refers to the enslavement of any of the world's European ethnic groups throughout human history, whether perpetrated by non-Europeans or by other Europeans. Slavery in ancient Rome was frequently dependent on a person's socio-economic status and national affiliation, and thus included European slaves. It was also common for European people to be enslaved and traded in the Muslim world; European women, in particular, were highly sought-after to be concubines in the harems of many Muslim rulers. Examples of such slavery conducted in Islamic empires include the Arab slave trade, the Barbary slave trade, the Ottoman slave trade, and the Black Sea slave trade, among others.

Jan Janszoon van Haarlem, commonly known as Reis Mourad the Younger, was a Dutch pirate who later became a Barbary corsair in Ottoman Algeria and the Republic of Salé. After being captured by Algerian corsairs off Lanzarote in 1618, he converted to Islam and changed his name to Mourad. He became one of the most famous of the 17th-century Barbary corsairs. Together with other corsairs, he helped establish the independent Republic of Salé at the city of that name, serving as the first President and Commander. He also served as Governor of Oualidia.

The Turkish Abductions were a series of slave raids by pirates from Algier and Salé that took place in Iceland in the summer of 1627.

This timeline of the history of piracy in the 1630s is a chronological list of key events involving pirates between 1630 and 1639.

The Barbary slave trade involved the capture and selling of white European slaves at slave markets in the largely independent Ottoman Barbary states. European slaves were captured by Barbary pirates in slave raids on ships and by raids on coastal towns from Italy to Ireland, and the southwest of Britain, as far north as Iceland and into the Eastern Mediterranean.

The Corcu Loígde, meaning Gens of the Calf Goddess, also called the Síl Lugdach meic Itha, were a kingdom centred in West County Cork who descended from the proto-historical rulers of Munster, the Dáirine, of whom they were the central royal sept. They took their name from Lugaid Loígde "Lugaid of the Calf Goddess", a King of Tara and High King of Ireland, son of the great Dáire Doimthech. A descendant of Lugaid Loígde, and their most famous ancestor, is the legendary Lugaid Mac Con, who is listed in the Old Irish Baile Chuinn Chétchathaig. Closest kin to the Corcu Loígde were the Dál Fiatach princes of the Ulaid.

The Republic of Salé, also known as the Bou Regreg Republic and the Republic of the Two Banks, was a city-state maritime corsair republic based at Salé in Morocco during the 17th century, located at the mouth of the Bou Regreg river. It was founded by Moriscos from the town of Hornachos, in western Spain. The Moriscos were the descendants of Muslims who were nominally converted to Christianity, and were subject to mass deportation during Philip III's reign, following the expulsion of the Moriscos decrees. The republic's main commercial activities were the Barbary slave trade and piracy during its brief existence in the 17th century.

Slavery on the Barbary Coast refers to the enslavement of people taken captive by the Barbary corsairs of North Africa.

Carbery's Hundred Isles are the islands along the coast of the Baronies of Carbery West and Carbery East, successors to the medieval Barony of Carbery, on the Celtic Sea, in the far south-west of Ireland. It is a term which includes those islands in and around Long Island Bay and Roaringwater Bay, County Cork.

Events from the year 1631 in Ireland.

O'Driscoll is an Irish surname. It is derived from the Gaelic Ó hEidirsceoil. The O'Driscolls were rulers of the Dáirine sept of the Corcu Loígde until the early modern period; their ancestors were Kings of Munster until the rise of the Eóganachta in the 7th century. At the start of the 13th century, three prominent branches of the family came into existence: O'Driscoll Mor, O'Driscoll Og, and O'Driscoll Beara. The Ó prefix was dropped by many in Ireland during the 17th and 18th centuries. The surname is now most prominent in the Irish counties of Cork and Kerry.

The Crooke Baronetcy of Baltimore, County Cork was a title in the Baronetage of Ireland. It was created for Sir Thomas Crooke, 1st Baronet in 1624. The Crooke family came originally from Cransley in Northamptonshire; Thomas Crooke, the father of the first baronet, was a well-known preacher of strongly Calvinist views.

Sir Thomas Crooke, 1st Baronet, of Baltimore (1574–1630) was an English-born politician, lawyer and landowner in seventeenth-century Ireland. He is chiefly remembered as the founder of the town of Baltimore, County Cork, which he developed into a flourishing port, but which was largely destroyed shortly after his death in the Sack of Baltimore 1631. He sat in the Irish House of Commons as member for Baltimore in the Parliament of 1613–1615. He was the first of the Crooke baronets of Baltimore, and ancestor of the Crooke family of Crookstown House.

Samuel Crooke was a seventeenth-century cleric of the Church of England and a noted preacher. During the English Civil War he was a staunch supporter of the Parliamentary cause.

Helkiah Crooke was Court physician to King James I of England. He is best remembered for his textbook on anatomy, Mikrokosmographia, a Description of the Body of Man. He was the first qualified doctor to be appointed Keeper of Royal Bethlem Hospital, but his conduct as Keeper was so unsatisfactory that he was eventually removed from that office on the grounds of corruption and absenteeism.

Sir Walter Coppinger was a member of the Irish nobility from County Cork, Ireland, who was a magistrate of Cork city, a lawyer, a landlord, and a moneylender. Coppinger came from one of the most prominent families in Cork city; though himself of Hiberno-Norse rather than Old English or Gaelic descent, he was hostile to the English settlement of Cork, and had a reputation for ruthlessness.

Sir Fineen O'Driscoll was an Irish clan chief who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth I. He was more commonly known as The Rover and also known as Fineen of the Ships. He was married to Eileen, daughter of Sir Owen MacCarthy Reagh the 16th Prince of Carbery, whose grandmother Eleanor was a daughter of Gearóid Mór FitzGerald, 8th Earl of Kildare. His eldest son, Connor, was the Lord of Castlehaven. His daughter Eileen married Richard Coppinger, a brother of Sir Walter Coppinger with whom he had numerous disputes over land that continued up to O'Driscoll's death. Another son Fineen was born in 1585. His daughter Mary was captured by a pirate named Ali Krussa and sold into the Barbary slave trade. He also had an illegitimate son, Gilly Duff. Fineen was also brother-in-law to Donal II O'Donovan and the two together with Owen MacCarthy Reagh's family are all noted in collaboration on numerous occasions.

Cloghan Castle is a ruined tower house on Castle Island in Lough Hyne in West Cork, Ireland. While no longer standing, it was originally at least three storeys tall. Castle Cloghan was once the main stronghold of the Irish clan O'Driscoll, but was abandoned after their Chief, Sir Fineen O'Driscoll, died there in 1629. The mid-19th century collapse of the ruins is said to have been caused by the barking of a ghostly black dog.