Washington Heights is a neighborhood in the northern part of the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It is named for Fort Washington, a fortification constructed at the highest natural point on Manhattan by Continental Army troops to defend the area from the British forces during the American Revolutionary War. Washington Heights is bordered by Inwood to the north along Dyckman Street, by Harlem to the south along 155th Street, by the Harlem River and Coogan's Bluff to the east, and by the Hudson River to the west.

The Harlem River is an 8-mile (13 km) tidal strait in New York City, New York, flowing between the Hudson River and the East River and separating the island of Manhattan from the Bronx on the United States mainland.

Spuyten Duyvil Creek is a short tidal estuary in New York City connecting the Hudson River to the Harlem River Ship Canal and then on to the Harlem River. The confluence of the three water bodies separate the island of Manhattan from the Bronx and the rest of the mainland. Once a distinct, turbulent waterway between the Hudson and Harlem rivers, the creek has been subsumed by the modern ship canal.

Highbridge is a residential neighborhood geographically located in the central-west section of the Bronx, New York City. Its boundaries, starting from the north and moving clockwise, are the Cross-Bronx Expressway to the north, Jerome Avenue to the east, Macombs Dam Bridge to the south, and the Harlem River to the west. Ogden Avenue is the primary thoroughfare through Highbridge.

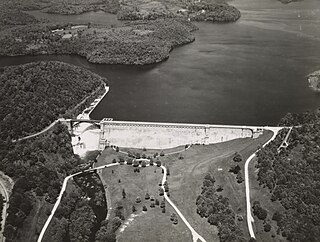

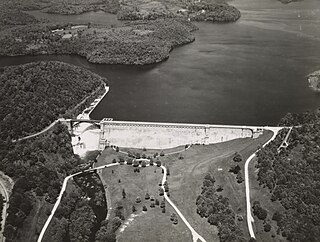

The New Croton Dam is a dam forming the New Croton Reservoir, both parts of the New York City water supply system. It stretches across the Croton River near Croton-on-Hudson, New York, about 22 miles (35 km) north of New York City.

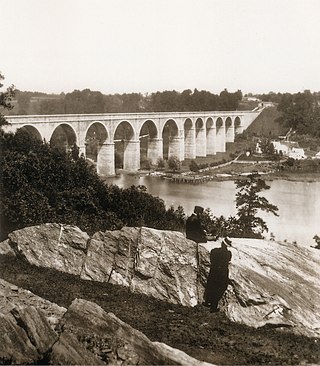

The Croton Aqueduct or Old Croton Aqueduct was a large and complex water distribution system constructed for New York City between 1837 and 1842. The great aqueducts, which were among the first in the United States, carried water by gravity 41 miles (66 km) from the Croton River in Westchester County to reservoirs in Manhattan. It was built because local water resources had become polluted and inadequate for the growing population of the city. Although the aqueduct was largely superseded by the New Croton Aqueduct, which was built in 1890, the Old Croton Aqueduct remained in service until 1955.

The Macombs Dam Bridge is a swing bridge across the Harlem River in New York City, connecting the boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx. The bridge is operated and maintained by the New York City Department of Transportation (NYCDOT).

The Hudson Line is a commuter rail line owned and operated by the Metro-North Railroad in the U.S. state of New York. It runs north from New York City along the east shore of the Hudson River, terminating at Poughkeepsie. The line was originally the Hudson River Railroad, and eventually became the Hudson Division of the New York Central Railroad. It runs along what was the far southern leg of the Central's famed "Water Level Route" to Chicago.

The Alexander Hamilton Bridge is an eight-lane steel arch bridge that carries traffic over the Harlem River between the boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx in New York City. The bridge connects the Trans-Manhattan Expressway in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan with the Cross Bronx Expressway as part of Interstate 95 and U.S. 1.

The Washington Bridge is a 2,375-foot (724 m)-long arch bridge over the Harlem River in New York City between the boroughs of Manhattan and the Bronx. The crossing, opened in 1888, connects 181st Street and Amsterdam Avenue in Washington Heights, Manhattan, with University Avenue in Morris Heights, Bronx. It carries six lanes of traffic, as well as sidewalks on both sides. Ramps at either end of the bridge connect to the Trans-Manhattan Expressway and the Cross Bronx Expressway, and serves as a connector/highway to the highway itself.

Van Cortlandt Park is a 1,146-acre (464 ha) park located in the borough of the Bronx in New York City. Owned by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation, it is managed with assistance from the Van Cortlandt Park Alliance. The park, the city's third-largest, was named for the Van Cortlandt family, which was prominent in the area during the Dutch and English colonial periods.

A combination of aqueducts, reservoirs, and tunnels supplies fresh water to New York City. With three major water systems stretching up to 125 miles (201 km) away from the city, its water supply system is one of the most extensive municipal water systems in the world.

The University Heights Bridge is a steel-truss revolving swing bridge across the Harlem River in New York City. It connects West 207th Street in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan with West Fordham Road in the University Heights neighborhood of the Bronx. The bridge is operated and maintained by the New York City Department of Transportation.

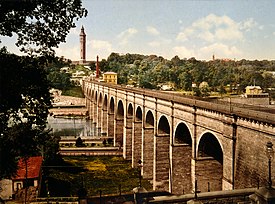

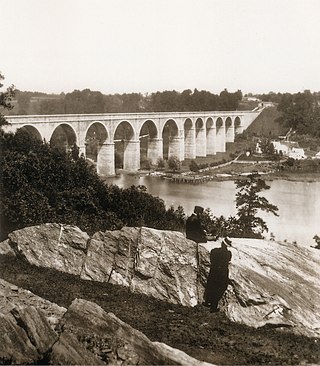

Highbridge Park is a public park on the western bank of the Harlem River in Washington Heights, Manhattan, New York City. It stretches between 155th Street and Dyckman Street in Upper Manhattan. The park is operated by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. The City maintains the southern half of the park, while the northern half is maintained by the non-profit New York Restoration Project. Prominent in the park are the Manhattan end of the High Bridge, the High Bridge Water Tower, and the Highbridge Play Center.

The Muscoot Reservoir is a reservoir in the New York City water supply system in northern Westchester County, New York, located directly north of the village of Katonah. Part of the system's Croton Watershed, it is 25 miles north of the City.

The Manhattan Waterfront Greenway is a waterfront greenway for walking or cycling, 32 miles (51 km) long, around the island of Manhattan, in New York City. The largest portions are operated by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation. It is separated from motor traffic, and many sections also separate pedestrians from cyclists. There are three principal parts — the East, Harlem and Hudson River Greenways.

Highbridge Reservoir was a reservoir in the New York City water supply system, which received water from a portion of the Croton Aqueduct system. It was located on Amsterdam Avenue between 172nd Street and 174th Street, in Upper Manhattan adjacent to the High Bridge Water Tower and the High Bridge across the Harlem River Valley. The reservoir covered about 7 acres (28,000 m2), was 16 feet (4.9 m) deep, and had a total capacity of 10,794,000 US gallons (40,860,000 L).

Concourse is a neighborhood in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of the Bronx which includes the Bronx County Courthouse, the Bronx Museum of the Arts, and Yankee Stadium. Its boundaries, starting from the north and moving clockwise, are East 169th Street to the north, Webster Avenue to the east, East 149th Street to the south, and Jerome Avenue and Harlem River to the west. The neighborhood is divided into three subsections: West Concourse, East Concourse, and Concourse Village with the Grand Concourse being its main thoroughfare.

Aqueduct Walk is a community park in The Bronx, New York City, located between Kingsbridge Road and West Tremont Avenue. It spans over two zip codes and two Bronx community boards. Its facilities include basketball courts, restrooms, playground and water sprinklers. The park forms part of the Old Croton Aqueduct and is a New York City scenic landmark.