The 1967 Atlantic hurricane season was an active Atlantic hurricane season overall, producing 13 nameable storms, of which 6 strengthened into hurricanes. The season officially began on June 1, 1967, and lasted until November 30, 1967. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in the Atlantic Ocean. The season's first system, Tropical Depression One, formed on June 10, and the last, Tropical Storm Heidi, lost tropical characteristics on November 2.

The 1969 Atlantic hurricane season was the most active Atlantic hurricane season since the 1933 season, and was the final year of the most recent positive Atlantic multidecadal oscillation (AMO) era. The hurricane season officially began on June 1, and lasted until November 30. Altogether, 12 tropical cyclones reached hurricane strength, the highest number on record at the time; a mark not surpassed until 2005. The season was above-average despite an El Niño, which typically suppresses activity in the Atlantic Ocean, while increasing tropical cyclone activity in the Pacific Ocean. Activity began with a tropical depression that caused extensive flooding in Cuba and Jamaica in early June. On July 25, Tropical Storm Anna developed, the first named storm of the season. Later in the season, Tropical Depression Twenty-Nine caused severe local flooding in the Florida Panhandle and southwestern Georgia in September.

The 1918 Atlantic hurricane season was inactive, with a total of six tropical storms developing, four of which intensified into hurricanes. Two of the season's hurricanes made Landfall in the United States, and one became a major hurricane, which is Category 3 or higher on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson scale. Additionally, there were four suspected tropical depressions, including one that began the season on June 19 and one that ended the season when it dissipated on October 19. The early 20th century lacked modern forecasting and documentation, and thus, the hurricane database from these years may be incomplete. Four previously unknown tropical cyclones were identified using records, including historical weather maps and ship reports, while information on the known storms was amended.

The 1919 Florida Keys hurricane was a massive and damaging tropical cyclone that swept across areas of the northern Caribbean Sea and the United States Gulf Coast in September 1919. Remaining an intense Atlantic hurricane throughout much of its existence, the storm's slow movement and sheer size prolonged and enlarged the scope of the hurricane's effects, making it one of the deadliest hurricanes in United States history. Impacts were largely concentrated around the Florida Keys and South Texas areas, though lesser but nonetheless significant effects were felt in Cuba and other areas of the United States Gulf Coast. The hurricane's peak strength in Dry Tortugas in the lower Florida Keys made it one of the most powerful Atlantic hurricanes to make landfall in the United States.

The 1979 Pacific hurricane season was an inactive North Pacific hurricane season, featuring 10 named storms, 6 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes. All tropical cyclone activity this season was confined to the Eastern Pacific, east of 140°W. For the first time since 1977, no tropical cyclones formed in, or entered into the Central Pacific, between 140°W and the International Date Line.

The 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was an event in the annual tropical cyclone season in the north Atlantic Ocean. It was the second most active Atlantic hurricane season in recorded history, and the most extreme in the satellite era. Officially, the season began on June 1, 2005 and ended on November 30, 2005. These dates, adopted by convention, historically delimit the period in each year when most tropical systems form. The season's first storm, Tropical Storm Arlene, developed on June 8. The final storm, Tropical Storm Zeta, formed in late December and persisted until January 6, 2006. Zeta is only the second December Atlantic storm in recorded history to survive into January, joining Hurricane Alice in 1955.

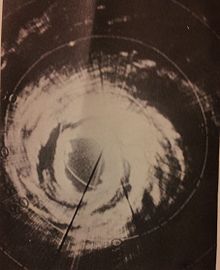

Hurricane Gladys was the farthest tropical cyclone from the United States to be observed by radar in the Atlantic basin since Hurricane Carla in 1961. The seventh named storm and fifth hurricane of the 1975 Atlantic hurricane season, Gladys developed from a tropical wave while several hundred miles southwest of Cape Verde on September 22. Initially, the tropical depression failed to strengthen significantly, but due to warm sea surface temperatures and low wind shear, it became Tropical Storm Gladys by September 24. Despite entering a more unfavorable environment several hundred miles east of the northern Leeward Islands, Gladys became a Category 1 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale on September 28. Shortly thereafter, the storm reentered an area favorable for strengthening. Eventually, a well-defined eye became visible on satellite imagery.

Hurricane Dora was one of few tropical cyclones to track across all three north Pacific basins and the first since Hurricane John in 1994. The fourth named storm, third hurricane, and second major hurricane of the 1999 Pacific hurricane season, Dora developed on August 6 from a tropical wave to the south of Mexico. Forming as a tropical depression, the system gradually strengthened and was upgraded to Tropical Storm Dora later that day. Thereafter Dora began heading in a steadily westward direction, before becoming a hurricane on August 8. Amid warm sea surface temperatures and low wind shear, the storm continued to intensify, eventually peaking as a 140 mph (220 km/h) Category 4 hurricane on August 12.

The meteorological history of Hurricane Ivan, the longest tracked tropical cyclone of the 2004 Atlantic hurricane season, lasted from late August through late September. The hurricane developed from a tropical wave that moved off the coast of Africa on August 31. Tracking westward due to a ridge, favorable conditions allowed it to develop into Tropical Depression Nine on September 2 in the deep tropical Atlantic Ocean. The cyclone gradually intensified until September 5, when it underwent rapid deepening and reached Category 4 status on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale; at the time Ivan was the southernmost major North Atlantic hurricane on record.

The 2008 Atlantic hurricane season was an event in the annual tropical cyclone season in the north Atlantic Ocean. An above-average Atlantic hurricane season season, it was the first on record to have a major hurricane in every month from July to November.

The 1995 Atlantic hurricane season was an event in the annual tropical cyclone season in the north Atlantic Ocean. This Atlantic hurricane season saw a near-record number of named tropical storms. This extremely active season followed four consecutive years in which there was below normal activity. The season officially began on June 1, 1995 and ended on November 30, 1995. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical systems form. The season's first system, Hurricane Allison, developed on June 3; its last, Hurricane Tanya, became extratropical on November 2.

The 1972 Atlantic hurricane season was a cycle of the annual tropical cyclone season in the Atlantic Ocean in the Northern Hemisphere. It was a significantly below average season, having only four fully tropical named storms, the fewest since 1930. It was one of only five Atlantic hurricane seasons since 1944 to have no major hurricanes, the others being 1968, 1986, 1994, and 2013. The season officially began on June 1, 1972 and ended on November 30, 1972. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical systems form. However, storm formation is possible at any time of the year, as demonstrated in 1972 by the formation of Subtropical Storm Alpha on May 23. The season's final storm, Subtropical Storm Delta, dissipated on November 7.

The 2009 Atlantic hurricane season was an event in the annual tropical cyclone season in the North Atlantic Ocean. It was a below-average Atlantic hurricane season with nine named storms, the fewest since the 1997 season. The season officially began on June 1, 2009, and ended on November 30, 2009, dates that conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic basin. The first storm to form was Tropical Depression One on May 28, 2009, while the last storm, Hurricane Ida, dissipated on November 10.

Hurricane Inga is the third longest-lived Atlantic hurricane on record. The 11th tropical cyclone and 9th named storm of the 1969 Atlantic hurricane season, Inga developed on September 20 in the central Atlantic and tracked westward. After attaining tropical storm status, the system deteriorated into a depression, but once again intensified several days later. The storm eventually peaked in strength on October 5, with winds corresponding to Category 2 on the modern-day Saffir–Simpson hurricane scale. Throughout its path, Inga underwent several changes in direction and oscillations in strength, before dissipating on October 15, 25 days after it formed. Despite its duration, Inga caused little damage, and mostly remained over open waters.

The 2010 Atlantic hurricane season was an event in the annual tropical cyclone season in the north Atlantic Ocean. It was one of the most active Atlantic hurricane seasons since record keeping began in 1851 as 19 named storms formed. The season officially began on June 1, 2010, and ended on November 30, 2010, dates that conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic basin. The first storm to form was Hurricane Alex, on June 25; and the last to dissipate was Hurricane Tomas, on November 7.

The 2011 Atlantic hurricane season was an event in the annual hurricane season in the north Atlantic Ocean. It was well above average, with 19 tropical storms forming. Even so, it was the first season on record in which the first eight storms failed to attain hurricane strength. The season officially began on June 1, 2011, and ended on November 30, 2011, dates that conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic basin. The season's first storm, Tropical Storm Arlene did not form until June 28. The final storm to develop, Tropical Storm Sean, dissipated on November 11.

The 2012 Atlantic hurricane season was an event in the annual hurricane season in the north Atlantic Ocean. For the third year in a row there were 19 named storms. The season officially began on June 1, 2012, and ended on November 30, 2012, dates that conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones develop in the Atlantic basin. Surprisingly, two preseason storms formed: Alberto on May 19, and Beryl on May 26. This was the first such occurrence since the 1951 season. The final storm to dissipate was Sandy, on October 29. Altogether, ten storms became hurricanes, of which two intensified into major hurricanes.

The 1888 Louisiana hurricane was a major hurricane that caused significant flooding and wind damage to the Mississippi River Delta and the Mississippi Valley in late August 1888. It was the third tropical cyclone and second hurricane of the 1888 Atlantic hurricane season.

Severe Tropical Cyclone Ernie was one of the quickest strengthening tropical cyclones on record. Ernie was the first Category 5 severe tropical cyclone in the Australian region since Cyclone Marcia in 2015, and also the strongest tropical cyclone in the Australian region since Cyclone Ita in 2014. Ernie developed from a tropical low into a cyclone south of Indonesia in the northeast Indian Ocean on 6 April 2017, and proceeded to intensify extremely rapidly to a Category 5 severe tropical cyclone. A few days later, on 10 April, the system was downgraded below cyclone intensity following a period of rapid weakening, located southwest of its original position. Ernie had no known impacts on any land areas.

Hurricane Dorian was the strongest hurricane to affect The Bahamas on record, causing catastrophic damage on the islands of Abaco Islands and Grand Bahama, in early September 2019. The cyclone's intensity, as well as its slow forward motion near The Bahamas, broke numerous records. The fifth tropical cyclone, fourth named storm, second hurricane, and first major hurricane of the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season, Dorian originated from a westward-traveling tropical wave, that departed from the western coast of Africa on August 19. The system organized into a tropical depression and later a tropical storm, both on August 24.