Diabetes insipidus (DI) is a condition characterized by large amounts of dilute urine and increased thirst. The amount of urine produced can be nearly 20 liters per day. Reduction of fluid has little effect on the concentration of the urine. Complications may include dehydration or seizures.

Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a potentially life-threatening complication of diabetes mellitus. Signs and symptoms may include vomiting, abdominal pain, deep gasping breathing, increased urination, weakness, confusion and occasionally loss of consciousness. A person's breath may develop a specific "fruity" or acetone smell. The onset of symptoms is usually rapid. People without a previous diagnosis of diabetes may develop DKA as the first obvious symptom.

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water that disrupts metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds intake, often resulting from excessive sweating, health conditions, or inadequate consumption of water. Mild dehydration can also be caused by immersion diuresis, which may increase risk of decompression sickness in divers.

Hyponatremia or hyponatraemia is a low concentration of sodium in the blood. It is generally defined as a sodium concentration of less than 135 mmol/L (135 mEq/L), with severe hyponatremia being below 120 mEq/L. Symptoms can be absent, mild or severe. Mild symptoms include a decreased ability to think, headaches, nausea, and poor balance. Severe symptoms include confusion, seizures, and coma; death can ensue.

Thirst is the craving for potable fluids, resulting in the basic instinct of animals to drink. It is an essential mechanism involved in fluid balance. It arises from a lack of fluids or an increase in the concentration of certain osmolites, such as sodium. If the water volume of the body falls below a certain threshold or the osmolite concentration becomes too high, structures in the brain detect changes in blood constituents and signal thirst.

Polydipsia is excessive thirst or excess drinking. The word derives from Greek πολυδίψιος (poludípsios) 'very thirsty', which is derived from Ancient Greek πολύς (polús) 'much, many' and δίψα (dípsa) 'thirst'. Polydipsia is a nonspecific symptom in various medical disorders. It also occurs as an abnormal behaviour in some non-human animals, such as in birds.

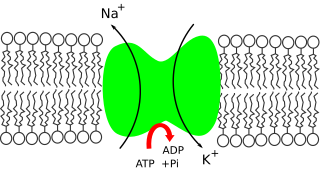

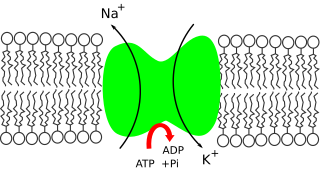

Electrolyte imbalance, or water-electrolyte imbalance, is an abnormality in the concentration of electrolytes in the body. Electrolytes play a vital role in maintaining homeostasis in the body. They help to regulate heart and neurological function, fluid balance, oxygen delivery, acid–base balance and much more. Electrolyte imbalances can develop by consuming too little or too much electrolyte as well as excreting too little or too much electrolyte. Examples of electrolytes include calcium, chloride, magnesium, phosphate, potassium, and sodium.

Hypokalemia is a low level of potassium (K+) in the blood serum. Mild low potassium does not typically cause symptoms. Symptoms may include feeling tired, leg cramps, weakness, and constipation. Low potassium also increases the risk of an abnormal heart rhythm, which is often too slow and can cause cardiac arrest.

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), also known as the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIAD), is characterized by a physiologically inappropriate release of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) either from the posterior pituitary gland, or an ectopic non-pituitary source, such as an ADH-secreting tumor in the lung. Unsuppressed ADH causes a physiologically inappropriate increase in solute-free water being reabsorbed by the tubules of the kidney to the venous circulation leading to hypotonic hyponatremia.

Hyperchloremia is an electrolyte disturbance in which there is an elevated level of chloride ions in the blood. The normal serum range for chloride is 96 to 106 mEq/L, therefore chloride levels at or above 110 mEq/L usually indicate kidney dysfunction as it is a regulator of chloride concentration. As of now there are no specific symptoms of hyperchloremia; however, it can be influenced by multiple abnormalities that cause a loss of electrolyte-free fluid, loss of hypotonic fluid, or increased administration of sodium chloride. These abnormalities are caused by diarrhea, vomiting, increased sodium chloride intake, renal dysfunction, diuretic use, and diabetes. Hyperchloremia should not be mistaken for hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis as hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis is characterized by two major changes: a decrease in blood pH and bicarbonate levels, as well as an increase in blood chloride levels. Instead those with hyperchloremic metabolic acidosis are usually predisposed to hyperchloremia.

Water intoxication, also known as water poisoning, hyperhydration, overhydration, or water toxemia, is a potentially fatal disturbance in brain functions that can result when the normal balance of electrolytes in the body is pushed outside safe limits by excessive water intake.

Saline is a mixture of sodium chloride (salt) and water. It has a number of uses in medicine including cleaning wounds, removal and storage of contact lenses, and help with dry eyes. By injection into a vein, it is used to treat hypovolemia such as that from gastroenteritis and diabetic ketoacidosis. Large amounts may result in fluid overload, swelling, acidosis, and high blood sodium. In those with long-standing low blood sodium, excessive use may result in osmotic demyelination syndrome.

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, recently renamed arginine vasopressin resistance (AVP-R) and previously known as renal diabetes insipidus, is a form of diabetes insipidus primarily due to pathology of the kidney. This is in contrast to central or neurogenic diabetes insipidus, which is caused by insufficient levels of vasopressin. Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus is caused by an improper response of the kidney to vasopressin, leading to a decrease in the ability of the kidney to concentrate the urine by removing free water.

Primary polydipsia and psychogenic polydipsia are forms of polydipsia characterised by excessive fluid intake in the absence of physiological stimuli to drink. Psychogenic polydipsia caused by psychiatric disorders—oftentimes schizophrenia—is frequently accompanied by the sensation of dry mouth. Some conditions with polydipsia as a symptom are non-psychogenic. Primary polydipsia is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Central diabetes insipidus, recently renamed arginine vasopressin deficiency (AVP-D), is a form of diabetes insipidus that is due to a lack of vasopressin (ADH) production in the brain. Vasopressin acts to increase the volume of blood (intravascularly), and decrease the volume of urine produced. Therefore, a lack of it causes increased urine production and volume depletion.

Sodium ions are necessary in small amounts for some types of plants, but sodium as a nutrient is more generally needed in larger amounts by animals, due to their use of it for generation of nerve impulses and for maintenance of electrolyte balance and fluid balance. In animals, sodium ions are necessary for the aforementioned functions and for heart activity and certain metabolic functions. The health effects of salt reflect what happens when the body has too much or too little sodium. Characteristic concentrations of sodium in model organisms are: 10 mM in E. coli, 30 mM in budding yeast, 10 mM in mammalian cell and 100 mM in blood plasma.

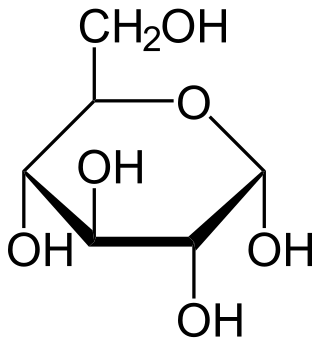

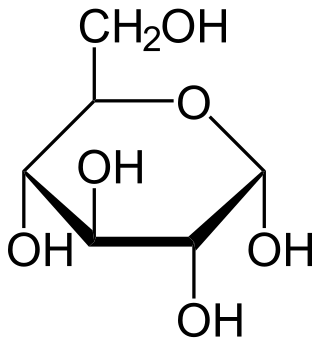

Intravenous sugar solution, also known as dextrose solution, is a mixture of dextrose (glucose) and water. It is used to treat low blood sugar or water loss without electrolyte loss. Water loss without electrolyte loss may occur in fever, hyperthyroidism, high blood calcium, or diabetes insipidus. It is also used in the treatment of high blood potassium, diabetic ketoacidosis, and as part of parenteral nutrition. It is given by injection into a vein.

Adipsia, also known as hypodipsia, is a symptom of inappropriately decreased or absent feelings of thirst. It involves an increased osmolality or concentration of solute in the urine, which stimulates secretion of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) from the hypothalamus to the kidneys. This causes the person to retain water and ultimately become unable to feel thirst. Due to its rarity, the disorder has not been the subject of many research studies.

Lithium toxicity, also known as lithium overdose, is the condition of having too much lithium. Symptoms may include a tremor, increased reflexes, trouble walking, kidney problems, and an altered level of consciousness. Some symptoms may last for a year after levels return to normal. Complications may include serotonin syndrome.

Salt poisoning is an intoxication resulting from the excessive intake of sodium either in solid form or in solution. Salt poisoning sufficient to produce severe symptoms is rare, and lethal salt poisoning is possible but even rarer. The lethal dose of table salt is roughly 0.5–1 gram per kilogram of body weight.