The Godavari is India's second longest river after the Ganga. Its source is in Triambakeshwar, Maharashtra. It flows east for 1,465 kilometres (910 mi), draining the states of Maharashtra (48.6%), Telangana (18.8%), Andhra Pradesh (4.5%), Chhattisgarh (10.9%) and Odisha (5.7%). The river ultimately empties into the Bay of Bengal through an extensive network of tributaries. Measuring up to 312,812 km2 (120,777 sq mi), it forms one of the largest river basins in the Indian subcontinent, with only the Ganga and Indus rivers having a larger drainage basin. In terms of length, catchment area and discharge, the Godavari is the largest in peninsular India, and had been dubbed as the Dakshin Ganga.

Ghaghara, also called Karnali is a perennial trans-boundary river originating on the Tibetan Plateau near Lake Manasarovar. It cuts through the Himalayas in Nepal and joins the Sharda River at Brahmaghat in India. Together they form the Ghaghara River, a major left bank tributary of the Ganges. With a length of 507 kilometres (315 mi) it is the longest river in Nepal. The total length of Ghaghara River up to its confluence with the Ganges at Revelganj in Bihar is 1,080 kilometres (670 mi). It is the largest tributary of the Ganges by volume and the second longest tributary of the Ganges by length after Yamuna.

The Daman Ganga also called Dawan River is a river in western India. The river's headwaters are on the western slope of the Western Ghats range, and it flows west into the Arabian Sea. The river flows through Maharashtra and Gujarat states, as well as the Union territory of Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu. The industrial towns of Vapi, Dadra and Silvassa lie on the north bank of the river, and the town of Daman occupies both banks of the river's estuary.

The Godavari River has its catchment area in seven states of India: Maharashtra, Telangana, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Odisha. The number of dams constructed in Godavari basin is the highest among all the river basins in India. Nearly 350 major and medium dams and barrages had been constructed in the river basin by the year 2012.

The Kosi or Koshi is a trans-boundary river which flows through Tibet, Nepal and India. It drains the northern slopes of the Himalayas in Tibet and the southern slopes in Nepal. From a major confluence of tributaries north of the Chatra Gorge onwards, the Kosi River is also known as Saptakoshi for its seven upper tributaries. These include the Tamor River originating from the Kanchenjunga area in the east and Arun River and Sun Kosi from Tibet. The Sun Koshi's tributaries from east to west are Dudh Koshi, Bhote Koshi, Tamakoshi River, Likhu Khola and Indravati. The Saptakoshi crosses into northern Bihar, India where it branches into distributaries before joining the Ganges near Kursela in Katihar district.

Hirakud Dam is built across the Mahanadi River, about 15 kilometres (9 mi) from Sambalpur in the state of Odisha in India. Behind the dam extends a lake, Hirakud Reservoir, 55 km (34 mi) long. It is one of the first major multipurpose river valley projects started after India's independence.

Pollution of the Ganges, the largest river in India, poses significant threats to human health and the larger environment. Severely polluted with human waste and industrial contaminants, the river provides water to about 40% of India's population across 11 states, serving an estimated population of 500 million people which is more than any other river in the world.

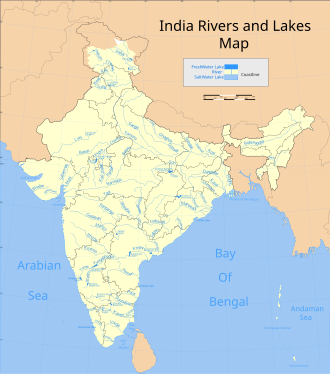

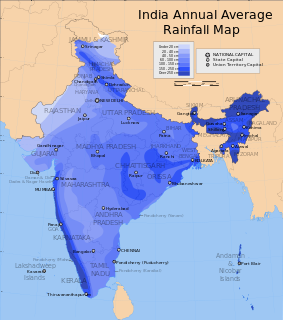

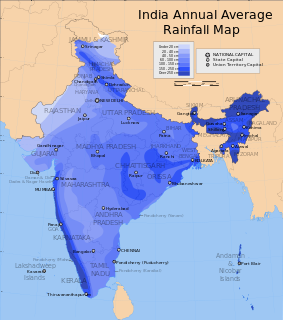

Water resources in India includes information on precipitation, surface and groundwater storage and hydropower potential. India experiences an average precipitation of 1,170 millimetres (46 in) per year, or about 4,000 cubic kilometres (960 cu mi) of rains annually or about 1,720 cubic metres (61,000 cu ft) of fresh water per person every year. India accounts for 18% of the world population and about 4% of the world’s water resources. One of the solutions to solve the country’s water woes is to create Indian Rivers Inter-link.c Some 80 percent of its area experiences rains of 750 millimetres (30 in) or more a year. However, this rain is not uniform in time or geography. Most of the rains occur during its monsoon seasons, with the north east and north receiving far more rains than India's west and south. Other than rains, the melting of snow over the Himalayas after winter season feeds the northern rivers to varying degrees. The southern rivers, however experience more flow variability over the year. For the Himalayan basin, this leads to flooding in some months and water scarcity in others. Despite extensive river system, safe clean drinking water as well as irrigation water supplies for sustainable agriculture are in shortage across India, in part because it has, as yet, harnessed a small fraction of its available and recoverable surface water resource. India harnessed 761 cubic kilometres (183 cu mi) (20 percent) of its water resources in 2010, part of which came from unsustainable use of groundwater. Of the water it withdrew from its rivers and groundwater wells, India dedicated about 688 cubic kilometres (165 cu mi) to irrigation, 56 cubic kilometres (13 cu mi) to municipal and drinking water applications and 17 cubic kilometres (4.1 cu mi) to industry.

The Telugu Ganga project is a joint water supply scheme implemented in 1980s by the then Andhra Pradesh chief minister N.T.Ramarao and Tamilnadu Chief minister M. G. Ramachandran to provide drinking water to Chennai city in Tamil Nadu. It is also known as the Krishna Water Supply Project, since the source of the water is the Krishna river in erstwhile Andhra Pradesh. Water is drawn from the Srisailam reservoir and diverted towards Chennai through a series of inter-linked canals, over a distance of about 406 kilometres (252 mi), before it reaches the destination at the Poondi reservoir near Chennai. The main checkpoints en route include the Somasila reservoir in Penna River valley, the Kandaleru reservoir, the 'Zero Point' near Uthukkottai where the water enters Tamil Nadu territory and finally, the Poondi reservoir, also known as Satyamurthy Sagar. From Poondi, water is distributed through a system of link-canals to other storage reservoirs located at Red Hills, Sholavaram and Chembarambakkam.

Interbasin transfer or transbasin diversion are terms used to describe man-made conveyance schemes which move water from one river basin where it is available, to another basin where water is less available or could be utilized better for human development. The purpose of such designed schemes can be to alleviate water shortages in the receiving basin, to generate electricity, or both. Rarely, as in the case of the Glory River which diverted water from the Tigris to Euphrates River in modern Iraq, interbasin transfers have been undertaken for political purposes. While ancient water supply examples exist, the first modern developments were undertaken in the 19th century in Australia, India and the United States; large cities such as Denver and Los Angeles would not exist as we know them today without these diversion transfers. Since the 20th century many more similar projects have followed in other countries, including Israel, Canada and China. Utilized alternatively, the Green Revolution in India and hydropower development in Canada could not have been accomplished without such man-made transfers.

The Kalpasar Project envisages building a 30 km dam across the Gulf of Khambat in India for establishing a huge fresh water coastal reservoir for irrigation, drinking and industrial purposes. The project with 30 km sea dam will have the capacity to store 10,000 million cubic meters fresh water, equating to 25% of Gujarat’s average annual rainwater flow, from the rivers of Saurashtra region namely Narmada, Mahi, Dhadhar, Sabarmati, Limbdi-Bhagovo, and two other minor rivers. A 10 lane road link will also be set up over the dam, greatly reducing the distance between Saurashtra and South Gujarat. The project, which will create world's largest freshwater lake in marine environment, will cost INR90,000 crore or US$12.75 billion excluding the cost of tidal power plant. Project entails construction of the main "Kalpasar dam" across Gulf of Khambat and another Bhadbhut barrage on Narmada river, as well as a canal connecting the two.

Jalayagnam or Jala Yagnam,, is a water management program in India. It has been implemented by Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh, India, Dr. Y. S. Rajasekhara Reddy as an election promise to the farmers of the state to bring 8.2 million acres under irrigation in five years. Y.S.R has taken required approvals from central government and NGTL. Also other required permissions for all the projects before he died. Like Site clearance, environmental clearance, R & R clearance, wildlife sanctuary clearance, forest clearance and technical advisory committee clearance. By the time he supposed to execute projects on phase manner, Y.S.R died in accident. Subsequently there was other issues like state bifurcation came to high intensity, subsequent Chief Ministers failed to give priority for Jalayagnam.

River Linking is a project of linking two or more rivers by creating a network of manually created reservoirs and canals, and providing land areas that otherwise does not have river water access and reducing the flow of water to sea using this means. It is based on the assumptions that surplus water in some rivers can be diverted to deficit rivers by creating a network of canals to interconnect the rivers.

The Upper Wardha Dam is an earthfill straight gravity dam across the Wardha River, a tributary of the Godavari River, near Simbhora village in Morshi taluk in Amravati district in the Indian state of Maharashtra. The dam provides multipurpose benefits of irrigation, drinking water supply, flood control and hydropower generation.

The Polavaram Project is an under construction multi-purpose irrigation National project on the Godavari River in the West Godavari District and East Godavari District in Andhra Pradesh. The project has been accorded national project status by the Union Government of India and will be the last to be accorded the status. Its reservoir back water spreads up to the Dummugudem Anicut and approx 115 km on Sabari River side. It is located 40 km to the upstream of Sir Arthur Cotton Barrage in Rajamahendravaram City and 25 km from Rajahmundry Airport. Thus back water spreads into parts of Chhattisgarh and Odisha States. It gives major boost to tourism sector in Godavari Districts as the reservoir covers the famous Papikonda National Park, Polavaram Hydro electric project(HEP) and National waterway 4 are in under construction at left side of the river.

The Pranahita Chevella Lift Irrigation Project is a lift irrigation project to harness the water of Pranhita tributary of Godavari river for use in the Telangana state of India. The river water diversion barrage across the Pranahita river is located at Thammidihatti village in Komaram Bheem district of Telangana. This lift canal is an inter river basin transfer link by feeding Godavari river water to Krishna river basin. The chief ministers of Telangana and Maharashtra states reached an agreement in 2016 to limit the full reservoir level (FRL) of the barrage at 148 m msl with 1.85 tmcft storage capacity. In the year 2016, this project is divided into two parts. The scheme with diversion canal from the Thammmidihatti barrage to connect to existing Yellampalli reservoir across the Godavari river is presently called Pranahita barrage lift irrigation project. This scheme is confined to providing irrigation facility to nearly 2,00,000 acres in Adilabad district using 44 tmcft water.

Indravati Dam is a gravity dam on the Indravati River a tributary of Godavari, about 90 km from Bhawanipatna in the state of Odisha in India. It is connected to the main Indravati reservoir via 4.32 km long and 7 m dia head race tunnel designed for a discharge capacity of 210 cumecs and terminating in a surge shaft. Currently it is the largest power producing dam in eastern India with a capacity of 600 MW.

Pattiseema Lift Irrigation Project is a river interlinking project which connects Godavari River to Krishna River. This project has thereby become the first of such irrigation type projects in the country to be completed in time without any budget enhancements. It also holds a record in Limca Book of Records. The project was Inaugurated by the Chief Minister of Andhra Pradesh Nara Chandrababu Naidu in March 2016 while the project was completed in one year record of time.

Vykuntapuram Barrage is an Indian barrage and water storage project. It is under construction on Krishna River 23 kilometers upstream of existing Prakasam Barrage with FRL 25M. It is designed to store 10 TMC of flood water coming from the Vyra and Munneru rivers. The backwater of this dam will extend beyond Pokkunuru to the toe of Pulichintala dam. Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Nara chandrababu Naidu laid the foundation stone for this project on 13 February 2019.