A soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) is a malignant tumor, a type of cancer, that develops in soft tissue. A soft-tissue sarcoma is often a painless mass that grows slowly over months or years. They may be superficial or deep-seated. Any such unexplained mass must be diagnosed by biopsy. Treatment may include surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and targeted drug therapy. Bone sarcomas are the other class of sarcomas.

A sarcoma is a malignant tumor, a type of cancer that arises from cells of mesenchymal origin. Connective tissue is a broad term that includes bone, cartilage, fat, vascular, or other structural tissues, and sarcomas can arise in any of these types of tissues. As a result, there are many subtypes of sarcoma, which are classified based on the specific tissue and type of cell from which the tumor originates. Sarcomas are primary connective tissue tumors, meaning that they arise in connective tissues. This is in contrast to secondary connective tissue tumors, which occur when a cancer from elsewhere in the body spreads to the connective tissue. Sarcomas are one of five different types of cancer, classified by the cell type from which they originate. The word sarcoma is derived from the Greek σάρκωμα sarkōma 'fleshy excrescence or substance', itself from σάρξsarx meaning 'flesh'.

Uterine cancer, also known as womb cancer, includes two types of cancer that develop from the tissues of the uterus. Endometrial cancer forms from the lining of the uterus, and uterine sarcoma forms from the muscles or support tissue of the uterus. Endometrial cancer accounts for approximately 90% of all uterine cancers in the United States. Symptoms of endometrial cancer include changes in vaginal bleeding or pain in the pelvis. Symptoms of uterine sarcoma include unusual vaginal bleeding or a mass in the vagina.

Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (MAHA) is a microangiopathic subgroup of hemolytic anemia caused by factors in the small blood vessels. It is identified by the finding of anemia and schistocytes on microscopy of the blood film.

A molar pregnancy, also known as a hydatidiform mole, is an abnormal form of pregnancy in which a non-viable fertilized egg implants in the uterus. It falls under the category of gestational trophoblastic diseases. During a molar pregnancy, the uterus contains a growing mass characterized by swollen chorionic villi, resembling clusters of grapes. The occurrence of a molar pregnancy can be attributed to the fertilized egg lacking an original maternal nucleus. As a result, the products of conception may or may not contain fetal tissue. These molar pregnancies are categorized into two types: partial moles and complete moles, where the term 'mole' simply denotes a clump of growing tissue or a ‘growth'.

A leiomyoma, also known as a fibroid, is a benign smooth muscle tumor that very rarely becomes cancer (0.1%). They can occur in any organ, but the most common forms occur in the uterus, small bowel, and the esophagus. Polycythemia may occur due to increased erythropoietin production as part of a paraneoplastic syndrome.

Endometrioid tumors are a class of tumors that arise in the uterus or ovaries that resemble endometrial glands on histology. They account for 80% of endometrial carcinomas and 20% of malignant ovarian tumors.

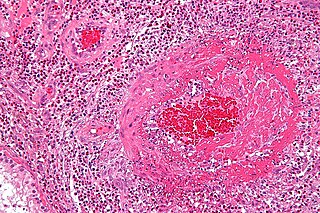

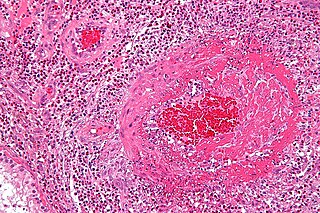

Fibrinoid necrosis is a specific pattern of irreversible, uncontrolled cell death that occurs when antigen-antibody complexes are deposited in the walls of blood vessels along with fibrin. It is common in the immune-mediated vasculitides which are a result of type III hypersensitivity. When stained with hematoxylin and eosin, they appear brightly eosinophilic and smudged.

Angiomas are benign tumors derived from cells of the vascular or lymphatic vessel walls (endothelium) or derived from cells of the tissues surrounding these vessels.

A fatty streak is the first grossly visible lesion in the development of atherosclerosis. It appears as an irregular yellow-white discoloration on the luminal surface of an artery. It consists of aggregates of foam cells, which are lipoprotein-loaded macrophages, located in the intima, the innermost layer of the artery, beneath the endothelial cells that layer the lumina through which blood flows. Fatty streaks may also include T cells, aggregated platelets, and smooth muscle cells. Although fatty streaks can develop into atheromas, not all are destined to become advanced lesions.

The uterine sarcomas form a group of malignant tumors that arises from the smooth muscle or connective tissue of the uterus.

Primitive neuroectodermal tumor is a malignant (cancerous) neural crest tumor. It is a rare tumor, usually occurring in children and young adults under 25 years of age. The overall 5 year survival rate is about 53%.

A malignant mixed Müllerian tumor, also known as malignant mixed mesodermal tumor (MMMT) is a cancer found in the uterus, the ovaries, the fallopian tubes and other parts of the body that contains both carcinomatous and sarcomatous components. It is divided into two types, homologous and a heterologous type. MMMT account for between two and five percent of all tumors derived from the body of the uterus, and are found predominantly in postmenopausal women with an average age of 66 years. Risk factors are similar to those of adenocarcinomas and include obesity, exogenous estrogen therapies, and nulliparity. Less well-understood but potential risk factors include tamoxifen therapy and pelvic irradiation.

Medullary breast carcinoma is a rare type of breast cancer that is characterized as a relatively circumscribed tumor with pushing, rather than infiltrating, margins. It is histologically characterized as poorly differentiated cells with abundant cytoplasm and pleomorphic high grade vesicular nuclei. It involves lymphocytic infiltration in and around the tumor and can appear to be brown in appearance with necrosis and hemorrhage. Prognosis is measured through staging but can often be treated successfully and has a better prognosis than other infiltrating breast carcinomas.

Vinay Kumar is the Lowell T. Coggeshall Distinguished Service Professor of Pathology at the University of Chicago, where he was also the Chairman (2000-2016) of the Department of Pathology. He is a recipient of Life Time Achievement Award by National Board of Examinations.

Fat necrosis is a form of necrosis that is caused by the action of lipases on adipocytes.

Genital leiomyomas are leiomyomas that originate in the dartos muscles, or smooth muscles, of the genitalia, areola, and nipple. They are a subtype of cutaneous leiomyomas that affect smooth muscle found in the scrotum, labia, or nipple. They are benign tumors, but may cause pain and discomfort to patients. Genital leiomyoma can be symptomatic or asymptomatic and is dependent on the type of leiomyoma. In most cases, pain in the affected area or region is most common. For vaginal leiomyoma, vaginal bleeding and pain may occur. Uterine leiomyoma may exhibit pain in the area as well as painful bowel movement and/or sexual intercourse. Nipple pain, enlargement, and tenderness can be a symptom of nipple-areolar leiomyomas. Genital leiomyomas can be caused by multiple factors, one can be genetic mutations that affect hormones such as estrogen and progesterone. Moreover, risk factors to the development of genital leiomyomas include age, race, and gender. Ultrasound and imaging procedures are used to diagnose genital leiomyomas, while surgically removing the tumor is the most common treatment of these diseases. Case studies for nipple areolar, scrotal, and uterine leiomyoma were used, since there were not enough secondary resources to provide more evidence.

Elliptocytes, also known as ovalocytes or cigar cells, are abnormally shaped red blood cells that appear oval or elongated, from slightly egg-shaped to rod or pencil forms. They have normal central pallor with the hemoglobin appearing concentrated at the ends of the elongated cells when viewed through a light microscope. The ends of the cells are blunt and not sharp like sickle cells.

Endometrial stromal sarcoma is a malignant subtype of endometrial stromal tumor arising from the stroma of the endometrium rather than the glands. There are three grades for endometrial stromal tumors, as follows. It was previously known as endolymphatic stromal myosis because of diffuse infiltration of myometrial tissue or the invasion of lymphatic channels.

Abul K. Abbas is an American pathologist at University of California San Francisco where he is Distinguished Professor in Pathology and former chair of its Department of Pathology. He is senior editor of the pathology reference book Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease along with Vinay Kumar, as well as Basic Immunology, and Cellular & Molecular Immunology. He was editor for Immunity from 1993 to 1996, and continues to serve as a member of the editorial board. He was one of the inaugural co-editors of the Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease for issues from 2006 to 2020. He has published nearly 200 scientific papers.