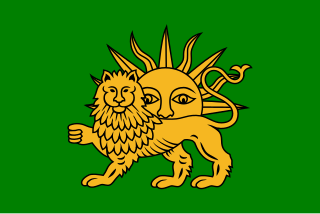

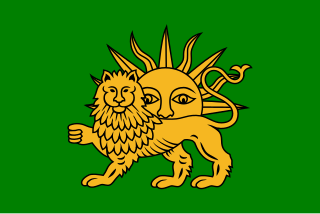

The Safavid dynasty was one of Iran's most significant ruling dynasties reigning from 1501 to 1736. Their rule is often considered the beginning of modern Iranian history, as well as one of the gunpowder empires. The Safavid Shāh Ismā'īl I established the Twelver denomination of Shīʿa Islam as the official religion of the Persian Empire, marking one of the most important turning points in the history of Islam. The Safavid dynasty had its origin in the Safavid order of Sufism, which was established in the city of Ardabil in the Iranian Azerbaijan region. It was an Iranian dynasty of Kurdish origin, but during their rule they intermarried with Turkoman, Georgian, Circassian, and Pontic Greek dignitaries, nevertheless they were Turkic-speaking and Turkified. From their base in Ardabil, the Safavids established control over parts of Greater Iran and reasserted the Iranian identity of the region, thus becoming the first native dynasty since the Sasanian Empire to establish a national state officially known as Iran.

Khwarazm or Chorasmia is a large oasis region on the Amu Darya river delta in western Central Asia, bordered on the north by the (former) Aral Sea, on the east by the Kyzylkum Desert, on the south by the Karakum Desert, and on the west by the Ustyurt Plateau. It was the center of the Iranian Khwarezmian civilization, and a series of kingdoms such as the Afrighid dynasty and the Anushtegin dynasty, whose capitals were Kath, Gurganj and – from the 16th century on – Khiva. Today Khwarazm belongs partly to Uzbekistan and partly to Turkmenistan.

Atropatene, also known as Media Atropatene, was an ancient Iranian kingdom established in c. 323 BC by the Persian satrap Atropates. The kingdom, centered in present-day northern Iran, was ruled by Atropates' descendants until the early 1st-century AD, when the Parthian Arsacid dynasty supplanted them. It was conquered by the Sasanians in 226, and turned into a province governed by a marzban ("margrave"). Atropatene was the only Iranian region to remain under Zoroastrian authority from the Achaemenids to the Arab conquest without interruption, aside from being briefly ruled by the Macedonian king Alexander the Great.

Gondophares I was the founder of the Indo-Parthian Kingdom and its most prominent king, ruling from 19 to 46. He probably belonged to a line of local princes who had governed the Parthian province of Drangiana since its disruption by the Indo-Scythians in c. 129 BC, and may have been a member of the House of Suren. During his reign, his kingdom became independent from Parthian authority and was transformed into an empire, which encompassed Drangiana, Arachosia, and Gandhara. He is generally known from the Acts of Thomas, the Takht-i-Bahi inscription, and silver and copper coins bearing his visage.

Phraates I was king of the Arsacid dynasty from 170/168 BC to 165/64 BC. He subdued the Mardians, conquered their territory in the Alborz mountains, and reclaimed Hyrcania from the Seleucid Empire. He died in 165/64 BC, and was succeeded by his brother Mithridates I, whom he had appointed his heir.

Artabanus II, incorrectly known in older scholarship as Artabanus III, was King of Kings of the Parthian Empire from 12 to 38/41 AD, with a one-year interruption. He was the nephew and successor of Vonones I. His father was a Dahae prince, whilst his mother was a daughter of the Parthian King of Kings Phraates IV

Vonones I was an Arsacid prince, who ruled as King of Kings of Parthian Empire from 8 to 12, and then subsequently as king of Armenia from 12 to 18. He was the eldest son of Phraates IV and was sent to Rome as a hostage in 10/9 BC in order to prevent conflict over the succession of Phraates IV's youngest son, Phraataces.

Arsaces II, was the Arsacid king of Parthia from 217 BC to 191 BC.

Characene, also known as Mesene (Μεσσήνη) or Meshan, was a kingdom founded by the Iranian Hyspaosines located at the head of the Persian Gulf mostly within modern day Iraq. Its capital, Charax Spasinou, was an important port for trade between Mesopotamia and India, and also provided port facilities for the city of Susa further up the Karun River. The kingdom was frequently a vassal of the Parthian Empire. Characene was mainly populated by Arabs, who spoke Aramaic as their cultural language. All rulers of the principality had Iranian names. Members of the Arsacid dynasty also ruled the state.

Spāhbed is a Middle Persian title meaning "army chief" used chiefly in the Sasanian Empire. Originally there was a single spāhbed, called the Ērān-spāhbed, who functioned as the generalissimo of the Sasanian army. From the time of Khosrow I on, the office was split in four, with a spāhbed for each of the cardinal directions. After the Muslim conquest of Persia, the spāhbed of the East managed to retain his authority over the inaccessible mountainous region of Tabaristan on the southern shore of the Caspian Sea, where the title, often in its Islamic form ispahbadh, survived as a regnal title until the Mongol conquests of the 13th century. An equivalent title of Persian origin, ispahsālār or sipahsālār, gained great currency across the Muslim world in the 10th–15th centuries.

The Iranian languages, also called Iranic languages, are a branch of the Indo-Iranian languages in the Indo-European language family that are spoken natively by the Iranian peoples, predominantly in the Iranian Plateau.

The Orontid dynasty, also known as the Eruandids or Eruandunis, ruled the Satrapy of Armenia until 330 BC and the Kingdom of Armenia from 321 BC to 200 BC. The Orontids ruled first as client kings or satraps of the Achaemenid Empire and after the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire established an independent kingdom. Later, a branch of the Orontids ruled as kings of Sophene and Commagene. They are the first of the three royal dynasties that successively ruled the antiquity-era Kingdom of Armenia.

New Persian, also known as Modern Persian and Dari (دری), is the current stage of the Persian language spoken since the 8th to 9th centuries until now in Greater Iran and surroundings. It is conventionally divided into three stages: Early New Persian, Classical Persian, and Contemporary Persian.

The Satrapy of Armenia, a region controlled by the Orontid dynasty, was one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid Empire in the 6th century BC that later became an independent kingdom. Its capitals were Tushpa and later Erebuni.

Sistān, known in ancient times as Sakastān, is a historical and geographical region in present-day Eastern Iran and Southern Afghanistan. Largely desert, the region is bisected by the Helmand River, the largest river in Afghanistan, which empties into the Hamun Lake that forms part of the border between the two countries.

The Kingdom of Sophene, was a Hellenistic-era political entity situated between ancient Armenia and Syria. Ruled by the Orontid dynasty, the kingdom was culturally mixed with Greek, Armenian, Iranian, Syrian, Anatolian and Roman influences. Founded around the 3rd century BCE, the kingdom maintained independence until c. 95 BCE when the Artaxiad king Tigranes the Great conquered the territories as part of his empire. Sophene laid near medieval Kharput, which is present day Elazığ.

Parthia is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in the 6th century BC, and formed part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Empire after the 4th-century BC conquests of Alexander the Great. The region later served as the political and cultural base of the Eastern Iranian Parni people and Arsacid dynasty, rulers of the Parthian Empire. The Sasanian Empire, the last state of pre-Islamic Iran, also held the region and maintained the seven Parthian clans as part of their feudal aristocracy.

Hyspaosines was an Iranian prince, and the founder of Characene, a kingdom situated in southern Mesopotamia. He was originally a Seleucid satrap installed by king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, but declared independence in 141 BC after the collapse and subsequent transfer of Seleucid authority in Iran and Babylonia to the Parthians. Hyspaosines briefly occupied the Parthian city of Babylon in 127 BC, where he is recorded in records as king (šarru). In 124 BC, however, he was forced to acknowledge Parthian suzerainty. He died in the same year, and was succeeded by his juvenile son Apodakos.